During the Cold War, NATO had nightmares of hundreds of thousands of Moscow’s troops pouring across international borders and igniting a major ground war with a democracy in Europe. Western governments feared that such a move by the Kremlin would lead to escalation—first to a world war and perhaps even to a nuclear conflict.

That was then; this is now.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is nearly a year old, and the Ukrainians are holding on. The Russians, so far, not only have been pushed back, but are taking immense casualties and material losses. For many Americans, the war is now just another conflict in the news. Do we need to worry about the nuclear threat of Putin’s war in Europe the way we worried about such things three decades ago?

Our staff writer Tom Nichols, an expert on nuclear weapons and the Cold War, counsels Americans not to be obsessed with nuclear escalation, but to be aware of the possibilities for accidents and miscalculations. You can hear his thoughts here:

The following is a transcript of the episode:

Tom Nichols: It’s been a year since the Russians invaded Ukraine and launched the biggest conventional war in Europe since the Nazis. One of the things that I think we’ve all worried about in that time is the underlying problem of nuclear weapons.

This is a nuclear-armed power at war with hundreds of thousands of people in the middle of Europe. This is the nightmare that American foreign policy has dreaded since the beginning of the nuclear age.

And I think people have kind of put it out of their mind, how potentially dangerous this conflict is, which is understandable, but also, I think, takes us away from thinking about something that is really the most important foreign problem in the world today.

During the Cold War, we would’ve thought about that every day, but these days, people just don’t think about it, and I think they should.

My name is Tom Nichols. I’m a staff writer at The Atlantic. And I’ve spent a lot of years thinking about nuclear weapons and nuclear war. For 25 years, I was a professor of national-security affairs at Naval War College.

For this episode of Radio Atlantic, I want to talk about nuclear weapons and what I think we should have learned from the history of the Cold War about how to think about this conflict today.

I was aware of nuclear weapons at a pretty young age because my hometown, Chicopee, Massachusetts, was home to a giant nuclear-bomber base, Strategic Air Command’s East Coast headquarters, which had the big B-52s that would fly missions with nuclear weapons directly to the Soviet Union.

I had a classic childhood of air-raid sirens, and hiding in the basement, and going under the desks, and doing all of that stuff. My high-school biology teacher had a grim sense of humor and told us, you know, because of the Air Force base, we were slated for instant destruction. He said, Yeah, if anything ever happens, we’re gone. We’re gone in seven or eight minutes. So I guess the idea of nuclear war and nuclear weapons was a little more present in my life at an earlier age than for a lot of other kids.

It’s been a long time since anyone’s really had to worry about global nuclear war. It’s been over 30 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall. I think people who lived through the Cold War were more than happy to forget about it. I know I am glad to have it far in the past. And I think younger people who didn’t experience it have a hard time understanding what it was all aboutand what that fear was about—because it’s part of ancient history now.

But I think people really need to understand that Cold War history to understand what’s going on today, and how decision makers in Washington and in Europe, and even in Moscow, are playing out this war—because many of these weapons are still right where we left them.

We have fewer of them, but we still have thousands of these weapons, many of them on a very short trigger. We could go from the beginning of this podcast to the end of the world, that short of [a] time. And it’s easy to forget that. During the Cold War, we were constantly aware of it, because it was the central influence on our foreign policy. But it’s important for us to look back at the history of the Cold War because we survived a long and very tense struggle with a nuclear-armed opponent. Now, some of that was through good and sensible policy. And some of it was just through dumb luck.

Of course, the first big crisis that Americans really faced where they had to think about the existential threat of nuclear weapons was the Cuban missile crisis, in October of 1962.

I was barely 2 years old. But living next to this big, plump nuclear target in Massachusetts, we actually knew people in my hometown who built fallout shelters. But we got through the Cuban missile crisis, in part because President Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev realized what was at stake.

The gamble to put missiles in Cuba had failed, and that we had to—as Khruschev put it in one of his messages—we had to stop pulling on the ends of the rope and tightening the knot of war. But we also got incredibly lucky.

There was a moment aboard a Soviet submarine where the sub commander thought they were under attack. And he wanted to use nuclear-tipped torpedoes to take out the American fleet, which would’ve triggered a holocaust.

I mean, it would’ve been an incredible amount of devastation on the world. Tens, hundreds of millions of people dead. And, um, fortunately a senior commander who had to consent to the captain’s idea vetoed the whole thing. He said, I don’t think that’s what’s happening. I don’t think they’re trying to sink us, and I do not consent. And so by this one lucky break with this one Soviet officer, we averted the end of the world. I mean, we averted utter catastrophe.

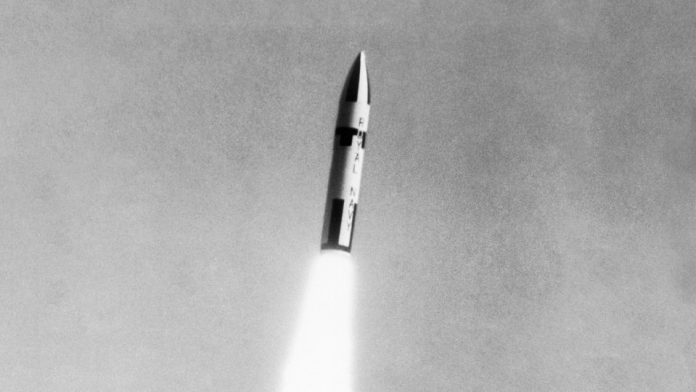

After the Cuban missile crisis, people are now even more aware of this existential threat of nuclear weapons and it starts cropping up everywhere, especially in our pop culture. I mean, they were always there in the ’50s; there were movies about the communist threat and attacks on America. But after the Cuban missile crisis, that’s when you start getting movies like Dr. Strangelove and Fail Safe.

Both were about an accidental nuclear war, which becomes a theme for most of the Cold War. In Dr. Strangelove, an American general goes nuts and orders an attack on Russia. And in Fail Safe, a piece of machinery goes bad and the same thing happens. And I think this reflected this fear that we now had to live with, this constant threat of something that we and the Soviets didn’t even want to do, but could happen anyway.

Even the James Bond movies, which were supposed to be kind of campy and fun, nuclear weapons were really often the source of danger in them. You know, bad guys were stealing them; people were trying to track our nuclear submarines. Throughout the ’60s, the ’70s, the ’80s nuclear weapons really become just kind of soaked into our popular culture.

We all know the Cuban missile crisis because it’s just part of our common knowledge about the world, even for people that didn’t live through it. I think we don’t realize how dangerous other times were. I always think of 1983 as the year we almost didn’t make it.

1983 was an incredibly tense year. President Ronald Reagan began the year calling the Soviet Union an “evil empire.” And announced that the United States would start pouring billions of dollars into an effort to defend against Soviet missiles, including space-based defenses, which the Soviets found incredibly threatening.

The relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union had just completely broken down. Really, by the fall of 1983, it felt like war was inevitable. It certainly felt like to me war was inevitable. There was kind of that smell of gunpowder in the air. We were all pretty scared. I was pretty scared. I was a graduate student at that point. I was 23 years old, and I was certain that this war, this cataclysmic war, was going to happen not only in my lifetime, but probably before I was 30 years old.

And then a lot of things happened in 1983 that elevated the level of tension between the United States and the Soviet Union to extraordinary levels. I would say really dangerous levels. The Soviets did their best to prove they were an evil empire by shooting down a fully loaded civilian airliner, killing 269 people. Just weeks after the shoot-down of the Korean airliner, Soviet Air Defenses got an erroneous report of an American missile launch against them. And this is another one of those cases where we were just lucky. We were just fortunate.

And in this case, it was a Soviet Air Defense officer, a lieutenant colonel, who saw this warning that the Americans had launched five missiles. And he said, You know, nobody starts World War III with five missiles. That seems wrong.

And he said, I just, I think the system—which still had some bugs—I just don’t think the system’s right. We’re gonna wait that out. We’re gonna ignore that. He was actually later reprimanded.

It was almost like he was reprimanded and congratulated at the same time, because if he had called Moscow and said, Look, I’m doing my duty. I’m reporting Soviet Air Defenses have seen American birds are in the air. They’re coming at us and over to you, Kremlin. And from there, a lot of bad decisions could have cascaded into World War III, especially after a year where we had been in such amazingly high conflict with each other.

Once again, just as after the Cuban missile crisis, the increase in tension in the 1980s really comes through in the popular culture. Music, movies, TV puts this sense of threat into the minds of ordinary Americans in a way that we just don’t have now. So people are going to the movies and they’re seeing movies like WarGames, once again about an accidental nuclear war. They’re seeing movies like Red Dawn, about a very intentional war by the Soviet Union against the United States.

The Soviets thought that Red Dawn was actually part of Reagan’s attempt to use Hollywood to prepare Americans for World War III. In music, Ronald Reagan as a character made appearances in videos by Genesis or by Men at Work. That November, the biggest television event in history was The Day After, which was a cinematic representation of World War III.

I mean, it was everywhere. By 1983, ’84, we were soaked in this fear of World War III. Nuclear war and Armageddon, no matter where you looked. I remember in the fall of 1983 going to see the new James Bond movie, one of the last Roger Moore movies, called Octopussy. And the whole plot amazed me because, of course, I was studying this stuff at the time, I was studying NATO and nuclear weapons.

And here’s this opening scene where a mad Soviet general says, If only we can convince the West to give up its nuclear weapons, we can finally invade and take over the world.

I saw all of these films as either a college student or a young graduate student, and again, it was just kind of woven into my life. Well, of course, this movie is about nuclear war. Of course, this movie is about a Soviet invasion. Of course, this movie is about, you know, the end of the world, because it was always there. It was always in the background. But after the end of the Cold War, that remarkable amount of pop-culture knowledge and just general cultural awareness sort of fades away.

I think one reason that people today don’t look back at the Cold War with the same sense of threat is that it all ended so quickly. We went from [these] terrifying year[s] of 1983, 1984. And then suddenly Gorbachev comes in; Reagan reaches out to him; Gorbachev reaches back. They jointly agree in 1985—they issue a statement that to this day, is still considered official policy by the Russian Federation and by the United States of America. They jointly declare a nuclear war can never be won and must never be fought.

And all of a sudden, by the summer of 1985, 1986, it’s just over, and, like, 40 years of tension just came to an end in the space of 20, 24 months. Something I just didn’t think I would see in my lifetime. And I think that’s really created a false sense of security in later generations.

After the Cold War, in the ’90s we have a Russia that’s basically friendly to the United States but nuclear weapons are still a danger. For example, in 1995, Norway launched a scientific satellite on top of a missile—I think they were gonna study the northern lights—and the scientists gave everybody notice, you know, We’re gonna be launching this satellite. You’re gonna see a missile launch from Norway.

Somebody in Russia just didn’t get the message, and the Russian defense people came to President Boris Yeltsin and they said, This might be a NATO attack. And they gave him the option to activate and launch Russian nuclear weapons. Yeltsin conferred with his people, and fortunately—because our relations were good, and because Boris Yeltsin and Bill Clinton had a good relationship, and because tensions were low in the world—Yeltsin says, Yeah, okay. I don’t buy that. I’m sure it’s nothing.

But imagine again, if that had been somebody else.

And that brings us to today. The first thing to understand is: We are in a better place than we were during the Cold War in many ways. During the Cold War, we had tens of thousands of weapons pointed at each other. Now by treaty, the United States and the Russian Federation each have about 1,500 nuclear weapons deployed and ready to go. Now, that’s a lot of nuclear weapons, but 1,500 is a lot better than 30,000 or 40,000.

Nonetheless, we are dealing with a much more dangerous Russian regime with this mafia state led by Vladimir Putin.

Putin is a mafia boss. There is no one to stop him from doing whatever he wants. And he has really convinced himself that he is some kind of great world historical figure who is going to reestablish this Christian Slavic empire throughout the former Soviet Union and remnants of the old Russian empire. And that makes him uniquely dangerous.

People might wonder why Putin is even bothering with nuclear threats, because we’ve always thought of Russia as this giant conventional power because that’s the legacy of the Cold War. We were outnumbered. NATO at the time was only 16 countries. We were totally outnumbered by the Soviets and the Warsaw Pact in everything—men, tanks, artillery—and of course, the only way we could have repulsed an attack by the Soviet Union into Europe would’ve been to use nuclear weapons.

I know earlier I mentioned the movie Octopussy. We’ve come a long way from the days when that mad Russian general could say, If only we got rid of nuclear weapons and NATO’s nuclear weapons, we could roll our tanks from Czechoslovakia to Poland through Germany and on into France.

What people need to understand is that Russia is now the weaker conventional power. The Russians are now the ones saying, Listen, if things go really badly for us and we’re losing, we reserve the right to use nuclear weapons. The difference between Russia now and NATO then is: NATO was threatening these nuclear weapons if they were invaded and they were being just rolled over by Soviet tanks on their way to the English Channel. The Russians today are saying, We started this war, and if it goes badly for us, we reserve the right to use nuclear weapons to get ourselves out of a jam.

This conventional weakness is actually what makes them more dangerous, because they’re now continually being humiliated in the field. And a country that had gotten by by convincing people that they were a great conventional power, that they had a lot of conventional capability, they’re being revealed now as a hollow power. They can’t even defeat a country a third of their own size.

And so when they’re running out of options, you can understand at that point where Putin says, Well, the only way to scramble the deck and to get a do-over here is to use some small nuclear weapon in that area to kind of sober everybody up and shock them into coming to the table or giving me what I want.

Now, I think that would be incredibly stupid. And I think a lot of people around the world, including China and other countries, have told Putin that would be a really bad idea. But I think one thing we’ve learned from this war is that Putin is a really lousy strategist who takes dumb chances because he’s just not very competent.

And that comes back to the Cold War lesson—that you don’t worry about someone starting World War III as much as you worry about bumbling into World War III because of a bunch of really dumb decisions by people who thought they were doing something smart and didn’t understand that they were actually doing something really dangerous.

So where does this leave us? This major war is raging through the middle of Europe, the scenario that we always dreaded during the Cold War; thousands and thousands of Moscow’s troops flooding across borders. What’s the right way to think about this? Perhaps the most important thing to understand is that this really is a war to defend democracy against an aggressive, authoritarian imperial state.

The front line of the fight for civilization, really, is in Ukraine now. If Ukraine loses this war, the world will be a very different place. That’s what makes it imperative that Americans think about this problem. I think it’s imperative to support Ukraine in this fight, but we should do that with a prudent understanding of real risks that haven’t gone away.

And so I think the Cold War provides some really good guidance here, which is to be engaged, to be aware, but not to be panicked. Not to become consumed by this fear every day, because that becomes paralyzing, that becomes debilitating. It’s bad for you as a person. And it’s bad for democracies’ ability to make decisions—because then you simply don’t make any decisions at all, out of fear.

I think it’s important not to fall victim to Cold War amnesia and forget everything we learned. But I also don’t think we should become consumed by a new Cold War paranoia where we live every day thinking that we’re on the edge of Armageddon.