On the afternoon of March 3, 2020, Governor Mike DeWine stepped to a lectern inside the Ohio statehouse to announce his most difficult pandemic decision. Ohio, the governor announced, would bar most spectators from the upcoming Arnold Classic, a bodybuilding and fitness festival hosted annually by Arnold Schwarzenegger that draws a quarter of a million people from 80 countries to Ohio’s capital city. “Everything in life is a risk,” DeWine said. “We all make calculated decisions. We don’t eliminate all risk in life. But with regard to the Arnold Classic, continuing it as planned was simply an unacceptable risk.”

Scrapping the Arnold was, at the time, an unprecedented move. It was the first such cancellation not only for Ohio, which didn’t yet have a single confirmed case of COVID-19, but for the entire country. The NBA was still playing games to packed arenas, and officials in California and elsewhere hadn’t yet started banning mass gatherings on account of the rapidly spreading novel coronavirus. “We’d joke during the pandemic later on, ‘Well, that seems like a no-brainer. Of course we would close that,’” DeWine recalled recently. “But when you do it and no one else is doing it …”

Over the next few weeks, DeWine would close schools, bars, restaurants, and other businesses, and, in a move that continues to draw condemnation from conservatives, postpone the March 17 presidential primary. The first-term Republican quickly became the nation’s most aggressive governor in confronting the pandemic. He acted faster in some respects than Democrats Gavin Newsom in California and Andrew Cuomo in New York, who was already winning acclaim for his daily televised briefings even as he delayed implementing far-reaching public-health restrictions. DeWine “did the right thing,” President Joe Biden, a former Senate colleague of his, said last year.

In a bygone era of American history—perhaps, say, 10 years ago—a big-state governor who earned bipartisan accolades for steering his state through a historic crisis would be cruising to reelection. DeWine has a sterling résumé: After winning his first House race in 1982, he has served as lieutenant governor, senator, attorney general, and now governor. He has been the ultimate Republican pragmatist, going as far right as necessary—but no further—to win and stay in office. Betty Montgomery, a Republican friend of DeWine’s who also served as Ohio’s attorney general, calls him “a governing Republican,” which reads as a compliment only in the context of the past several years of partisan warfare.

As governor, DeWine has notched conservative policy wins and handled Donald Trump deftly, managing to succeed in a state the former president won easily twice without either fully embracing or repudiating him. “He’s got to be one of the top five most successful politicians in the history of Ohio,” says the state’s current Republican Party chair, Bob Paduchik, a former DeWine aide who ran Trump’s 2020 campaign in the state. That is not idle praise in a state that produced eight presidents.

Yet it’s unclear whether Ohio Republicans will nominate him for another term this spring, or punish DeWine for the sin of believing in science and taking COVID-19 seriously. The governor has come under withering attack not only from his primary opponents but also from the bevy of Trumpist conservatives vying for Ohio’s open Senate seat. For the moment, however, DeWine appears to be in decent shape, a position he owes to both luck—his gubernatorial challengers are currently splitting the anti-DeWine vote, and the Senate race is hogging the spotlight—and the combination of savvy and tenacity that has defined his long career in politics. The primary, scheduled for May 3, will determine whether one of the last of the Reagan Republicans can survive one more election in the age of Donald Trump.

DeWine is as conservative a governor as Ohio has ever had. He’s cut income taxes, expanded gun rights, and, early in his tenure, signed a “heartbeat” bill that effectively bans abortion after six weeks, one of the most restrictive laws in the country. But his temperament and his leadership style have commanded respect and even, at times, admiration from Democrats. Last Christmas, he landed what Biden called “one of the biggest investments in manufacturing in American history”—a $20 billion deal from Intel to build a pair of semiconductor factories in central Ohio, generating as many as 20,000 new jobs in the state.

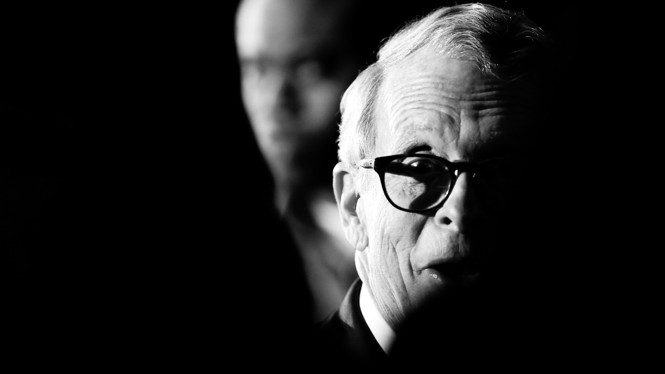

With blue-framed bifocals and a slight stoop that undersells his 5-foot-8-inch height, DeWine, 75, now projects an image that David Pepper, a former opponent and Democratic Party chair, likens to “a gentlemanly grandpa.” In part, it’s a statement of fact: DeWine is a father of eight and grandfather of 26. He and his wife of 55 years, Fran, met in the first grade in Yellow Springs, a small village outside Dayton where DeWine worked for his father’s seed company. A liberal college town, Yellow Springs is what its slightly more famous resident, Dave Chappelle, has called “a Bernie Sanders island in a Trump sea.”

The DeWines are unfailingly polite; when I interviewed the governor at his official residence last month, Fran sat next to him for part of the conversation and offered me a goody bag of homemade treats along with a booklet of recipes from her and Dolly Parton, a friend and partner on a project to provide free books to young children. Pepper describes DeWine as “genuinely nice,” as did several other Democrats I spoke with. That sets him apart from both Trump and DeWine’s predecessor as governor, John Kasich, another Republican with bipartisan credentials who, despite his image on the 2016 presidential-campaign trail, was famously prickly in private.

[Read: Ohio is now fully Trumpified]

DeWine first impressed Democrats just eight months into his term, in the aftermath of a mass shooting. In August 2019, the governor was standing on a stage, addressing a restive and angry crowd. Hours earlier, a 24-year-old gunman had shot 26 people outside a Dayton bar in just over half a minute, killing nine. While DeWine spoke, someone shouted, “Do something!” Then another person repeated the demand, and another, and another. Soon it became a chant, drowning out DeWine as he recalled the sudden death of one of his daughters in a car accident 26 years earlier. By the next day, the governor had responded with proposals to tighten background checks and make it easier for courts to confiscate firearms from citizens deemed a threat to themselves or others. “Some chanted, ‘Do something,’ and they were absolutely right,” DeWine said at a press conference. “We must do something, and that is exactly what we are going to do.”

The Democrats who praised DeWine at the time included Nan Whaley, the Dayton mayor, who would grow close to the governor as Ohio confronted the pandemic the next year. Republicans in the legislature, however, refused DeWine’s request for new gun-control measures, sending him only a “Stand Your Ground” bill that makes it legal for a person to shoot someone in self-defense without retreating first. DeWine signed the bill, a decision that Democrats viewed as a betrayal. Whaley, incensed, jumped into this year’s gubernatorial race, in which she’s battling former Cincinnati Mayor John Cranley for her party’s nomination. Conservatives in the legislature tested DeWine again earlier this month, sending the governor a bill that would eliminate the requirement that Ohioans get a permit to carry a concealed weapon. DeWine vacillated for several days, but under pressure from his primary opponents, he signed it, too.

To Democrats, DeWine’s acquiescence to conservatives on gun rights fits a pattern that repeated itself during his response to COVID-19. Local leaders, including Whaley, had applauded his early pandemic decision making, which was steadier than the leadership Trump was offering and represented a more aggressive response than that of governors in their own party. Whaley in particular helped buck up DeWine as he faced more and more opposition from the right. The two exchanged frequent messages of support and praise during the crisis, according to texts published last fall in response to a public-records request by the Cincinnati Enquirer. “Thx for your leadership. We are amplifying your message,” Whaley wrote in early March.

Yet by the end of April 2020, DeWine was wavering. He announced that the state would institute a mask mandate, only to reverse himself the next day, after blowback from Republicans. DeWine imposed a mandate again a few months later, during the state’s second COVID wave. But Democrats say he lost the stomach for tough pandemic leadership after Amy Acton, his Democratic state health director, who had become a target of conservative ire, left the government. “In the moment, I think he makes an emotional response that is the right response at times, and he thinks that he is strong enough and willing enough as a person to do what he knows is right. But then the politics and holding-on-to-power gets too important to him,” Whaley told me. “He completely rolls over.”

Ohio now sits in the middle of the pack on metrics such as cases, deaths, and vaccinations. “Mike DeWine’s record is no better than any other leader in the country. In fact, Ohio’s worse,” Cranley told me. “So I don’t really accept the idea that he was better on COVID.” Whaley told me that when she would confront DeWine for backing off public-health measures and other sensible policies, he would tell her, “I can’t lose the public.” But she believes he was talking about only part of the population. “The public is code for Mike DeWine’s extreme right-wing base,” Whaley said. “Because the public is with you on these issues.”

I put Whaley’s characterization to DeWine, and the governor disputed it only to a point. “I’m a pragmatic person,” he said. “You can lead, but sometimes if you get too far out front, you’ve got nobody behind you. It’s always a balance.” When he first tried to institute a mask mandate, he said, it “became evident to me that at that time during the pandemic, we weren’t going to have the support to do it.”

If DeWine wins the Republican primary, he’ll be the heavy favorite in the fall. Whaley and Cranley are pinning their hopes on anti-DeWine conservatives refusing to vote for the governor in the general election. (They also believe that DeWine could be hurt by a bribery scandal that has already led to the indictment and expulsion of the GOP speaker of the Ohio House.) To them, the secret to DeWine’s longevity as a member of the faltering Republican establishment is not difficult to divine. “He is relentless, and he is relentless in being a chameleon,” Cranley told me.

But if DeWine gets little credit from Democrats for his initial attempts at bipartisan leadership, he gets even less from his fellow conservatives for ultimately returning to their side. His opponents in the primary are denouncing him in similar language, as an old-guard pol, calculating and corrupt. Their challenge is to consolidate and mobilize a GOP base that sees DeWine in the same way.

Joe Blystone looks nothing like Mike DeWine. Nor, frankly, does he look like anyone who’s served in high office in this country in the past century. That’s half the point of his gubernatorial campaign pitch. Blystone, a farmer who has traversed Ohio in a large blue bus since early last year, wears a cowboy hat and a long, untrimmed gray-and-white beard that calls to mind old photographs of a Civil War general. He calls himself a constitutional conservative; others simply call him “The Cowboy.” “I just want to tell you tonight: President Trump is still my president!” Blystone told the crowd at a riverside restaurant in rural Ohio one evening in early March. The line generated by far the biggest applause of his nearly hour-long remarks.

“Many people forget what DeWine did to us two years ago,” Blystone said. “Well, I’m here to remind you.” Blystone went on to detail a litany of COVID-related grievances, assailing DeWine for postponing the 2020 presidential primary elections and for shutting down businesses that, in some cases, were never able to reopen.

In truth, no one in that restaurant needed the reminder, and it’s doubtful that many voters across the state do, either. Ohio dropped its COVID restrictions months ago, but as I spoke with people last month, DeWine’s handling of the pandemic was the first topic everyone mentioned—either positively or negatively—when I asked for opinions about the governor’s reelection bid. “He shut down small businesses but not Walmart,” Todd Blocker, a 55-year-old truck driver wearing a Back the Beard T-shirt at Blystone’s event, told me.

Blystone’s background—he’s never run for office—and his antipolitician appearance make it easy to mistake him for a fringe candidate, but he has captured 20 percent of the primary vote in recent public polls. Those surveys place him ahead of the Republican widely expected to be DeWine’s most formidable challenger, former Representative Jim Renacci. An early Trump supporter, Renacci told me that Trump personally recruited him for an ultimately unsuccessful 2018 challenge to Sherrod Brown, the state’s last remaining Democrat in statewide office. This time around, Renacci hired Trump’s former campaign manager Brad Parscale to advise his campaign, but the former president himself has stayed out of the race.

In an interview, Renacci made little effort to conceal his disappointment at Trump’s silence. He had spoken with Trump by phone just two days earlier, but if Renacci tried to persuade him on that call, he had clearly failed. “He’s always been a supporter,” Renacci said. “Look, in the end, I think he’s going to do what’s best for him, the state, me, whatever.” A few minutes later, he added, “I just think he wants to make sure that I can win.”

Renacci and Blystone are now bickering publicly over which candidate should drop out to help consolidate the anti-DeWine vote. The governor, meanwhile, is reaping the benefits of his divided opposition. A Fox News poll early last month found DeWine way up, with 50 percent of the vote compared with 21 percent for Blystone and 18 percent for Renacci. “I don’t think Mike DeWine has a serious challenge,” Paduchik, the Republican Party chair, told me.

A Trump endorsement of Renacci is probably the biggest threat to DeWine, whose handling of the former president is perhaps the governor’s most impressive political feat of the past four years. DeWine is nominally supportive of Trump and co-chaired his reelection campaign in Ohio. At the same time, he rejected Trump’s bogus claims of a stolen election and yet has somehow avoided, at least so far, the president’s retributive wrath.

Part of DeWine’s success in Trump management is undoubtedly luck, because he presided over a state that Trump won by eight points and did not face the pressure that governors such as Doug Ducey in Arizona and Brian Kemp in Georgia did when the president and his allies implored them to help overturn the election. But at least some of DeWine’s handling of the man who reshaped his party reflects raw political skill. DeWine is possessed of a self-discipline that frustrates his opponents on the right and the left, who tend to see it as evasiveness.

The key difference between Trump and DeWine is that the governor is conservative in both substance and style. “We’re not big show people, big drama people,” he told a business group in Athens, a college town in the Appalachian southeastern part of Ohio, last month. When I visited the governor in Columbus the next day, DeWine wandered deep into the weeds as he explained some of his statewide initiatives on education and economic development. But on the questions dividing the Republican Party at the moment, he resorted to generalities and offered up a demonstration of his famous restraint. He made clear that he remained a loyal Republican, saying he would support Josh Mandel, J. D. Vance, or any of the other Senate hopefuls who have been criticizing him and otherwise lurching to the right on the campaign trail.

“It’s a primary. People are going to say what they think they have to say,” DeWine said. “It doesn’t mean I like it, but in the end, I want Republicans to control the Senate and I want Mitch McConnell to be majority leader, not Chuck Schumer. Simple as that.” Should the party nominate Trump again in 2024? “I really think we have to resist talking about 2024 until we get 2022 done,” he said. I tried a different tack, asking the governor whether Trump was a positive presence in American public life at the moment. “You’re good,” he replied, “but I’m not going to go there.”

DeWine well understands that rank-and-file Republicans these days aren’t interested in pragmatism and dealmaking; they are, in fact, “big show people, big drama people,” who want their leaders to embrace the party’s showiest, most dramatic star. But as always, he has gone as far as he feels he needs to go to retain their support, and for now, he’ll go no further. His agenda, and his ambition, doesn’t extend beyond Ohio’s border. As someone who has seen more than a few elections in his 75 years, he noted that as soon as this year’s campaigns are over, everybody will be off and running for the 2024 prize, heading up to New Hampshire and out to Iowa. What about him? I asked, just to be sure. He laughed. “Not me,” the governor said.