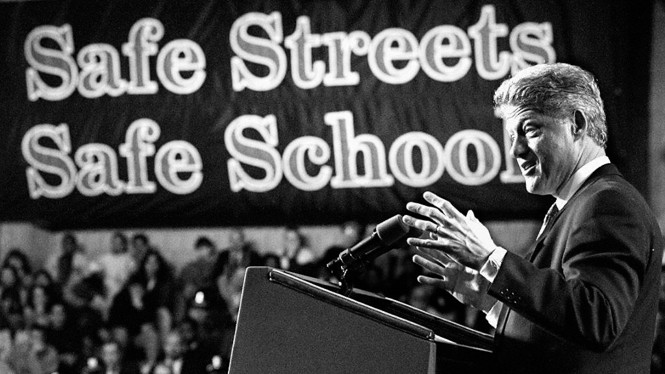

Maybe Bill Clinton got a few things right after all.

For years, Democrats have rarely cited Clinton and the centrist New Democrat movement he led through the ’90s except to renounce his “third way” approach to welfare, crime, and other issues as a violation of the party’s principles. Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, and even Bill Clinton himself have distanced themselves from key components of his record as president.

But now a loose constellation of internal party critics is reprising the Clintonites’ core arguments to make the case that progressives are steering Democrats toward unsustainable and unelectable positions, particularly on cultural and social questions.

Just like the centrists who clustered around Bill Clinton and the Democratic Leadership Council that he led decades ago, today’s dissenters argue that Democrats risk a sustained exodus from power unless they can recapture more of the culturally conservative voters without a college education who are drifting away from the party. (That group, these dissenters argue, now includes not only white Americans but also working-class Hispanics and even some Black Americans.) And just as then, these arguments face fierce pushback from other Democrats who believe that the centrists would sacrifice the party’s commitment to racial equity in a futile attempt to regain right-leaning voters irretrievably lost to conservative Republican messages.

Today’s Democratic conflict is not yet as sustained or as institutionalized as the earlier battles. Although dozens of elected officials joined the DLC, the loudest internal critics of progressivism now are mostly political consultants, election analysts, and writers—a list that includes the data scientist David Shor and a coterie of prominent left-of-center journalists (such as Matthew Yglesias, Ezra Klein, and Jonathan Chait) who have popularized his work; the longtime demographic and election analyst Ruy Teixeira and like-minded writers clustered around the website The Liberal Patriot; and the pollster Stanley B. Greenberg and the political strategist James Carville, two of the key figures in Clinton’s 1992 campaign. Compared with the early ’90s, “the pragmatic wing of the party is more fractured and leaderless,” says Will Marshall, the president of the Progressive Policy Institute, a centrist think tank that was initially founded by the DLC but that has long outlived its parent organization (which closed its doors in 2011).

For now, these dissenters from the party’s progressive consensus are mostly shouting from the bleachers. On virtually every major cultural and economic issue, the Democrats’ baseline position today is well to the left of their consensus in the Clinton years (and the country itself has also moved left on some previously polarizing cultural issues, such as marriage equality). As president, Biden has not embraced all of the vanguard liberal positions that critics such as Shor and Teixeira consider damaging, but neither has he publicly confronted and separated himself from the most leftist elements of his party—the way Clinton most famously did during the 1992 campaign when he accused the hip-hop artist Sister Souljah of promoting “hatred” against white people. Only a handful of elected officials—most prominently, incoming New York City Mayor Eric Adams—seem willing to take a more confrontational approach toward cultural liberals, as analysts such as Teixeira are urging. But if next year’s midterm elections go badly for the party, it’s possible, even likely, that more Democrats will join the push for a more Clintonite approach. And that could restart a whole range of battles over policy and political strategy that seemed to have been long settled.

The Democratic Leadership Council was launched in February 1985, a few months after Ronald Reagan won 49 states and almost 60 percent of the popular vote while routing the Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale. From the start, Al From, a congressional aide who was the driving force behind the group, combatively defined the DLC as an attempt to steer the party toward the center and reduce the influence of liberal constituency groups, including organized labor and feminists.

The organization quickly attracted support from moderate Democratic officeholders, mostly in the South and West and also mostly white and male (critics derided the group alternately as the “white male caucus” or “Democrats for the Leisure Class”). After moving cautiously in its first years, the DLC shifted to a more aggressive approach and found a larger audience following Michael Dukakis’s loss to George H. W. Bush in 1988. Losing to a generational political talent like Reagan amid a booming economic recovery was one thing, but when the gaffe-prone Bush beat Dukakis, who had moved to the center on economics, by portraying him as weak on crime and foreign policy, more Democrats responded to the DLC’s call for change. “That’s when it clicked in brains that we just don’t have an offer [to voters] that can sustain majority support around the country,” Marshall, who worked for the DLC since its founding, told me.

[Read: Who was Bill Clinton, anyway?]

The DLC responded to its larger audience by releasing what would become the enduring mission statement of the New Democrat movement. In September 1989, the Progressive Policy Institute, the think tank the DLC had formed a few months earlier, published a lengthy paper called “The Politics of Evasion.”

The paper’s authors, William Galston and Elaine Kamarck, were two Democratic activists with a scholarly bent, but on this occasion they wrote with a blowtorch. In the paper, they dismantled the common excuses for the party’s decline: bad tactics, unusually charismatic opponents, and the failure to mobilize enough nonvoters. Dukakis’s defeat meant that Democrats had lost five of the six previous presidential elections, averaging only 43 percent of the popular vote, and the party, Galston and Kamarck argued, needed to face the dire implications of that record. “Too many Americans,” they wrote, “have come to see the party as inattentive to their economic interests, indifferent if not hostile to their moral sentiments and ineffective in defense of their national security.”

The party had veered off course, they argued, because it had become dominated by “minority groups and white elites—a coalition viewed by the middle class as unsympathetic to its interests and its values.” Unless Democrats could reverse the perception among those middle-class voters that they too were profligate in spending and too permissive on social issues such as crime and welfare, the party was unlikely to win them back, even if a Republican president mismanaged the economy or Democrats convincingly tarred Republicans as favoring the wealthy. “All too often the American people do not respond to a progressive economic message, even when Democrats try to offer it, because the party’s presidential candidates fail to win their confidence in other key areas such as defense, foreign policy, and social values,” Galston and Kamarck wrote. “Credibility on these issues is the ticket that will get Democratic candidates in the door to make their affirmative economic case.”

The only way to prove to these disaffected middle-class voters that the party had changed, the pair suggested, was for centrists to publicly pick a fight with liberals. “Only conflict and controversy over basic economic, social, and defense issues are likely to attract the attention needed to convince the public that the party still has something to offer,” they declared.

Bill Clinton, who took over as DLC chairman a few months after “The Politics of Evasion” was published, “devoured these analyses of the Democrats’ difficulties as if they were so many French fries,” as Dan Balz and I wrote in our 1996 book, Storming the Gates. Clinton sanded down some of the sharpest edges of these ideas and adapted them into the folksy, populist style he had developed while repeatedly winning office in Arkansas, a state dominated by culturally conservative, mostly non-college-educated white Americans. But the basic prescription of the Democratic dilemma that Galston and Kamarck had identified remained a compass for him throughout his 1992 presidential campaign and eventually his presidency.

After a quarter century of futility, Clinton’s reformulation of the traditional Democratic message restored the party’s ability to compete for the White House. But after he left office, more Democrats came to view his approach as an unprincipled concession to white conservatives, particularly on issues such as crime and welfare. Compared with Clinton, Barack Obama generally pursued a much more liberal course, especially on social issues and especially as his presidency proceeded. Hillary Clinton, in her 2016 primary campaign, felt compelled to renounce decisions from her husband’s presidency on trade, LGBTQ rights, and crime (though not welfare reform). Similarly, in the 2020 primary race, Biden distanced himself from both the 1994 crime bill (which he had steered through the Senate) and welfare reform, without fully repudiating either. Even Bill Clinton, in a 2015 appearance before the NAACP, apologized for elements of the crime bill, which he acknowledged had contributed to the era of mass incarceration. With the DLC having folded a decade earlier, the PPI enduring only as a shadow of its earlier size and prominence, and other centrist organizations raising relatively fewer objections to the Democratic Party’s course, the rejection of Clintonism and the ascent of progressivism appeared complete as Biden took office.

Eleven tumultuous months later, the neo–New Democrats have emerged as arguably the loudest cluster of opposition to the party’s direction since the DLC’s heyday. But so far, the new critics of liberalism have not produced a critique of the party’s failures or a blueprint for its future as comprehensive as “The Politics of Evasion.” David Shor, a young data analyst and pollster who personally identifies as a democratic socialist, has promoted his ideas primarily through interviews with sympathetic journalists (taking criticism along the way for failing to document some of his assertions about polling results). Ruy Teixeira and his allies have advanced similar ideas in greater depth through essays primarily in their Substack project, The Liberal Patriot. Stan Greenberg, the pollster, summarized his approach in an extensive recent polling report on how to improve the party’s performance with working-class voters that he conducted along with firms that specialize in Hispanic (Equis Labs) and Black (HIT Strategies) voters.

These analysts don’t always agree with one another. But they do overlap on key points that echo central conclusions from “The Politics of Evasion.” Like Galston and Kamarck a generation ago, Shor, Teixeira, and Greenberg all argue that economic assistance alone won’t recapture voters who consider Democrats out of touch with their values on social and cultural issues. (Today’s critics don’t worry as much as the DLC did about the party appearing weak on national security.) “The more working class voters see their values as being at variance with the Democratic party brand,” Teixeira wrote recently in a direct echo of “Evasion,” “the less likely it is that Democrats will see due credit for even their measures that do provide benefits to working class voters.”

Also like Galston and Kamarck, Shor and Teixeira in particular argue that Democrats have steered off track on cultural issues because the party is unduly influenced by the preferences of well-educated white liberals. Like the pugnacious DLC founder Al From during the 1980s, Teixeira believes that Democrats can’t convince swing voters that the party is changing unless they publicly denounce activists advocating for positions such as defunding the police and loosening immigration enforcement at the border. Several Never Trump Republicans fearful that Biden’s faltering poll numbers will allow a Donald Trump revival have offered similar advice. (Shor also believes that Democrats must move to the center on cultural issues but he’s suggested that the answer is less to pick fights within the party than to simply downplay those issues in favor of economics, where the party’s agenda usually has more public support, an approach that has been described as “popularism.” “On the social issues, you want to take the median position,” he told me, “but really the game is that our positions are so unpopular, we have to do everything we can to keep them out of the conversation. Period.”)

[Derek Thompson: Democrats are getting crushed in the ‘vibes war’]

In all this, the critics are excavating arguments from the Clinton/DLC era that had been either repudiated or simply forgotten in recent years. Teixeira sees a “family resemblance” between his views and the case that Galston and Kamarck developed. Shor has more explicitly linked his critique to those years. “When I first started working on the Obama campaign in 2012, I hated all the last remnants of the Clinton era,” Shor told one interviewer. “There was an old conventional wisdom to politics in the ’90s and 2000s that we all forget … We’ve told ourselves very ideologically convenient stories about how those lessons weren’t relevant … and it turned out that wasn’t true. I see what I’m doing as rediscovering the ancient political wisdom of the past.”

When I spoke with him this week, Shor argued that his generation had incorrectly discarded lessons about holding the center of the electorate understood by Democrats of Clinton’s era, and even through the early stages of Obama’s presidency. The electorate today, he said, is less conservative than in Clinton’s day but more conservative than most Democrats want to admit. “It took me a long time to accept this, because it was very ideologically against what I wanted to be true, but the reality is, the way to win elections is to go against your party and to seem moderate,” Shor said. “I like to tell people that symbolic and ideological moderation are not just helpful but actually are the only things that matter to a big degree.”

As Teixeira told me, most of today’s critics reject the Clinton/DLC economic approach, which stressed deficit reduction, free trade, and deregulation in some areas, such as financial markets. Even the most conservative congressional Democrats, such as Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, have signaled that they will accept far more spending in Biden’s Build Back Better agenda than Clinton ever might have contemplated. Shor remains concerned that Democrats could spark a backlash by moving too far to the left on spending, but overall, most in the party would agree with Teixeira when he says, “You don’t see that kind of ideological divide between tax-and-spend Democrats and the self-styled apostles of the market like you had back in those days.”

On social issues, too, the range of Democratic opinion has also moved substantially to the left since the Clinton years. No Democrat today is calling for resurrecting the harsh sentencing policies, particularly for drug offenses, that many in the party supported as crime surged in the late ’80s and ’90s. All but two House Democrats voted for sweeping police-reform legislation this year. Similarly, Biden and congressional Democrats have unified around a provision that would permanently provide an expanded child tax credit to parents without any earnings, even though some Republicans, such as Senator Marco Rubio of Florida, claim that that would violate the principle of requiring work in the welfare-reform legislation that Clinton signed in 1996. The Democratic consensus has also moved decisively to the left on other social issues that bitterly divided the party in the Clinton years, including gun control, LGBTQ rights, and a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants.

All of these changes are rooted in the reconfiguration of the Democratic coalition and the broader electorate since the Clinton years. Compared with that era, Democrats today need fewer culturally conservative voters to win power. Roughly since the mid-’90s, white Americans without a college degree—the principal audience for the centrist critics—have fallen from about three-fifths of all voters to about two-fifths (give or take a percentage point or two, depending on the source). Over that same period, voters of color have nearly doubled, to about 30 percent of the total vote, and white voters with a college degree have ticked up to just above that level (again with slight variations depending on the source).

The change in the Democratic coalition has been even more profound. As recently as Clinton’s 1996 reelection, those non-college-educated white voters constituted nearly three-fifths of all Democrats, according to data from the Pew Research Center, with the remainder of the party divided about equally between college-educated white voters and minority voters. By 2020, the Democratic targeting firm Catalist, in its well-respected analysis of the election results, concluded that non-college-educated white Americans contributed only about one-third of Biden’s votes, far less than in 1996, only slightly more than white Americans with a college degree, and considerably less than people of color (who provided about two-fifths of Biden’s support). This ongoing realignment—in which Democrats have replaced blue-collar white voters who have shifted toward the GOP (particularly in small towns and rural areas) with minority voters and well-educated white voters clustered in the urban centers and inner suburbs of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas—has allowed the party to coalesce around a more uniformly liberal cultural agenda.

Shor, Teixeira, Greenberg, and like-minded critics now argue that this process has gone too far and that analysts (including me) who have highlighted the impact of demographic change on the electoral balance have underestimated the risks the Democratic Party faces from its erosion in white, non-college-educated support, especially in the Trump era. Although Democrats have demonstrated that they can reliably win the presidential popular vote with this new alignment—what I’ve called their “coalition of transformation”—the critics argue that the overrepresentation of blue-collar white voters across the Rust Belt, Great Plains, and Mountain West states means that Democrats will struggle to amass majorities in either the Electoral College or the Senate unless they improve their performance with those voters. Weakness with non-college-educated white voters outside the major metros also leaves Democrats with only narrow paths to a House majority, they argue. Shor has been the starkest in saying that these imbalances in the electoral system threaten years of Republican dominance if Democrats don’t regain some of the ground they have lost with working-class voters since Clinton’s time.

[Ron Brownstein: What Democrats need to realize before 2022]

These arguments probably would not have attracted as much notice if they were focused solely on those non-college-educated white Americans who have voted predominantly for Republicans since the ’80s and whose numbers are consistently shrinking as a share of the electorate (both nationally and even in the key Rust Belt swing states) by two or three percentage points every four years. What really elevated attention to these critiques was Trump’s unexpectedly improved performance in 2020 among Hispanics and, to a lesser extent, Black Americans. The neo–New Democrats have taken that as evidence that aggressive social liberalism—such as calls for defunding the police—is alienating not only white voters but now nonwhite working-class voters.

If it lasts, such a shift among working-class voters of color could largely negate the advantage that Democrats have already received, and expect moving forward, from the electorate’s growing diversity. “You won’t benefit that much from the changing ethnic demographic mix of the country if these overwhelmingly noncollege, nonwhite [voters] start moving in the Republican direction, and that concentrates the mind,” Teixeira told me.

As in the DLC era, almost every aspect of the neo–New Democrats’ critique is sharply contested.

One line of dispute is about how much social liberalism contributed to Trump’s gains last year with Hispanic and Black voters. Polls, such as the latest American Values survey, by the nonpartisan Public Religion Research Institute, leave no question that a substantial share of Black and especially Hispanic voters express culturally conservative views. Greenberg says in his recent study that non-college-educated Hispanics and Black Americans, as well as blue-collar white voters, all responded to a tough populist economic message aimed at the rich and big corporations, but only after Democrats explicitly rejected defunding the police. “You just didn’t get there [with those voters] unless you were for funding and respecting, but reforming, the police as part of your message,” Greenberg told me. “The same way that in his era and time … welfare reform unlocked a lot of things for Bill Clinton, it may be that addressing defunding the police unlocks things in a way that is similar.”

Yet some other Democratic analysts are skeptical that socially liberal positions on either policing or immigration were the driving force of Trump’s gains with minority voters (apart, perhaps, from a localized role for immigration in Hispanic South Texas counties near the border). Stephanie Valencia, the president of the polling firm Equis Labs, told me earlier this year that Biden might have performed better with Hispanics if the campaign debate had focused more on immigration; she believes that Trump benefited because the dialogue instead centered so much on the economy, which gave conservative Hispanics who “were worried about a continued shutdown [due] to COVID” a “permission structure” to support him. Terrance Woodbury, the CEO of the polling and messaging firm HIT Strategies, similarly says that although Black voters largely reject messaging about defunding the police, they remain intently focused on addressing racial inequity in policing and other arenas—and that a lack of perceived progress on those priorities might be the greatest threat to Black Democratic turnout in 2022.

Other political observers remain dubious that Democrats can regain much ground with working-class white voters through the strategies that the neo–New Democrats are offering, especially when the Trump-era GOP is appealing to their racial and cultural anxieties so explicitly. Even if Democrats follow the critics’ advice and either downplay or explicitly renounce cutting-edge liberal ideas on policing and “cancel culture,” the party is still irrevocably committed to gun control, LGBTQ rights (including same-sex marriage), legalization for millions of undocumented immigrants, greater accountability for police, and legal abortion. With so many obstacles separating Democrats from blue-collar white voters, there’s “not a lot of room” for Democrats to improve their standing with those voters, says Alan Abramowitz, an Emory University political scientist who has extensively studied blue-collar attitudes.

Rather than chasing the working-class white voters attracted to Trump’s messages by shifting right on crime and immigration, groups focused on mobilizing the growing number of nonwhite voters, such as Way to Win, argue that Democrats should respond with what they call the “class-race narrative.” That approach directly accuses Republicans of using racial division to distract from policies that benefit the rich, a message these groups say can both motivate nonwhite intermittent voters and convince some blue-collar white voters. “We’re much better off calling [Republicans] out—scorning them for trying to use race to divide us so that the entrenched can keep their privileges—and laying out a bold populist reform agenda that actually impacts people across lines of race,” says Robert Borosage, a longtime progressive strategist who served as a senior adviser to Jesse Jackson when he regularly sparred with the DLC during his presidential campaigns and after.

For their part, first-generation New Democrats such as Galston and Marshall believe that the current round of critics is unrealistic to assume that neutralizing cultural issues would give the party a free pass to expand government spending far more than Clinton considered politically feasible. Too many Democrats “think it’s about the things government can do for you, but lots of working people of all races … want opportunity … They want a way to get ahead of their own effort,” Marshall told me. Shor, unlike some of the other contemporary critics of progressivism, largely seconds that assessment. “There are things that people trust Republicans on and you have to neutralize those disadvantages by moving to the center on them, and that includes the size of government, that includes the deficit,” he said. “You have to make it seem that you care a lot about inflation, that you care a lot about the deficit, that you care about all of those things.”

[Read: Liberals are losing the culture wars]

Though Biden hasn’t directly engaged with these internal debates, in practice he’s landed pretty close to the critics’ formula. The president has overwhelmingly focused his time on trying to unify Democrats around the sweeping kitchen-table economic agenda embodied in his infrastructure and Build Back Better plans. He’s talked much less about social issues whether he’s agreeing with the left (as on many, though not all, of his approaches to the border) or dissenting from it (in his repeated insistence that he supports more funding, coupled with reform, for the police.) “I don’t know where his heart is on this stuff, but I think he’s a creature of the party and what he thinks is the party consensus,” Teixeira told me. “He doesn’t want to pick a fight.”

Yet despite Biden’s characteristic instinct to calm the waters, the debate seems destined to intensify around him. Galston, now a senior governance fellow at the Brookings Institution, has recently discussed with Kamarck writing an updated version of their manifesto. “Is there a basis for the kind of reflection and rethinking that was set in motion at the end of the 1980s? I think yes,” Galston told me. Meanwhile, organizations such as Way to Win are arguing that Democrats should worry less about recapturing voters drawn to Trump than mobilizing the estimated 91 million individuals who turned out to vote for the party in at least one of the 2016, 2018, and 2020 elections.

The one point on which both the neo–New Democrats and their critics most agree is that with so many Republicans joining Trump’s assault on the pillars of small-d democracy, the stakes in Democrats finding a winning formula are even greater today than they were when Clinton ran. “There’s a greater sense of urgency, I would say. Because if we had gotten it wrong in 1992, the country’s reward would have been George H. W. Bush, which wasn’t terrible at the time and in retrospect looks better,” Galston said. “This time if we get it wrong, the results of failure will be Donald Trump.”