Scientists don’t agree on whether approving COVID-19 boosters for certain non-elderly Americans, as the CDC did recently, was the right move. The president, the CDC, and the FDA have issued a series of conflicting statements on the issue. Some experts have indignantly resigned. Others have published frustrated op-eds.

President Joe Biden, who got a booster shot this week and called on other eligible Americans to do the same, remains enthusiastic. The split between Biden-administration scientists, such as Chief Medical Adviser Anthony Fauci and CDC Director Rochelle Walensky, and other scientists over boosters might seem confusing. One possible explanation for it has largely escaped notice: Vaccinated Americans seem to really want boosters, which means that the shots could have benefits that go well beyond extra protection against COVID. Those benefits could be psychological and economic—and, for the president, political.

The administration’s booster decision was not intended to inspire confidence or encourage economic activity, a White House official who was granted anonymity to discuss internal decision making told me. Biden was following the science and his experts’ recommendations, the official insisted. Every presidential administration claims that its decisions are the products of pure, high-minded policy debates. But like all political operations, Biden’s White House closely monitors public sentiment, and the president’s team is no doubt aware of how popular boosters are.

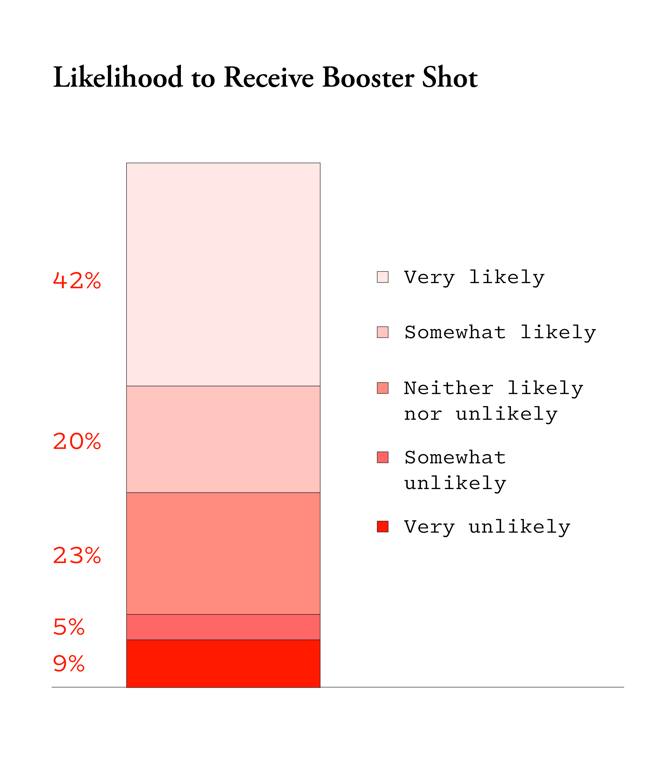

New data back up the idea that most vaccinated Americans are eager to get boosters. In a new Atlantic/Leger poll, 62 percent of vaccinated respondents said they are likely to get a booster shot of the COVID-19 vaccine. Even the majority of respondents in their 30s and 40s—considered a less at-risk population—said they’re likely to get a booster. The poll of 1,001 Americans was conducted from September 24 to 26. Our results mirror past polls suggesting that among people who take COVID-19 seriously, boosters are extremely popular. In several late-August polls, about three-quarters of vaccinated adults said they’d get one, and concern about the Delta variant was the leading reason they cited.

So far, boosters are less widely available in the U.S. than Biden had initially suggested they would be. In mid-August, the president said the government would “be ready to start this booster program during the week of September 20, in which time anyone [fully] vaccinated on or before January 20 will be eligible to get a booster shot.” The CDC has ultimately recommended boosters for a narrower group: People over 65 and nursing-home residents, as well as non-elderly frontline workers and those with underlying health conditions, starting this month. Perhaps to the chagrin of the Johnson & Johnson crowd, only Americans who received the Pfizer shot qualify for a booster right now.

Many scientists remain skeptical. There’s no evidence that vaccinated young and healthy people face an increased risk of hospitalization or death, even if their COVID-vaccine antibodies fade over time, says Céline Gounder, an infectious-disease expert at New York University. She was vaccinated eight months ago, but she doesn’t feel the need to get a booster. Non-elderly people with normal immune systems might never really need one, she told me. (In an interview with my colleague Ed Yong at The Atlantic Festival recently, Fauci disagreed, saying, “It is likely, for a real complete regimen, that you would need at least a third dose.”)

To political strategists, though, Biden’s promise of boosters for all is a no-brainer. It’s the Oprah Winfrey school of politics: YOU get a booster, and YOU get a booster. The Delta wave of COVID-19 cases “has led to a resurgence in COVID concern, especially among people who are already vaccinated,” says Matt Grossmann, a political-science professor at Michigan State University. Boosters are “one thing that can be offered that doesn’t have an obvious downside,” unlike a mandate or a lockdown.

Of course, launching a booster program right now might have less obvious costs. Administering boosters takes up the time and resources of health-care workers when they are already stretched. Billions more dollars will go to vaccine manufacturers at a time when many of Americans’ basic needs, such as food and shelter, aren’t being met. Some experts have argued that rather than boost Americans, the Biden administration should donate vaccine doses to poorer countries, some of which have administered so few doses that they won’t reach herd immunity until 2023. And, if further data support the need for boosters for all, future vaccination efforts could be hampered if the public sees boosters mainly as a political tool.

But those critiques may not sway many voters. “The American people are not going to blame Joe Biden for being too aggressive in combatting the pandemic,” says Jesse Ferguson, a Democratic strategist. “If there’s a fire in your neighborhood, nobody complains that the fire department sprayed too much water.” That’s perhaps why some governors were promoting boosters weeks before the CDC’s official announcement.

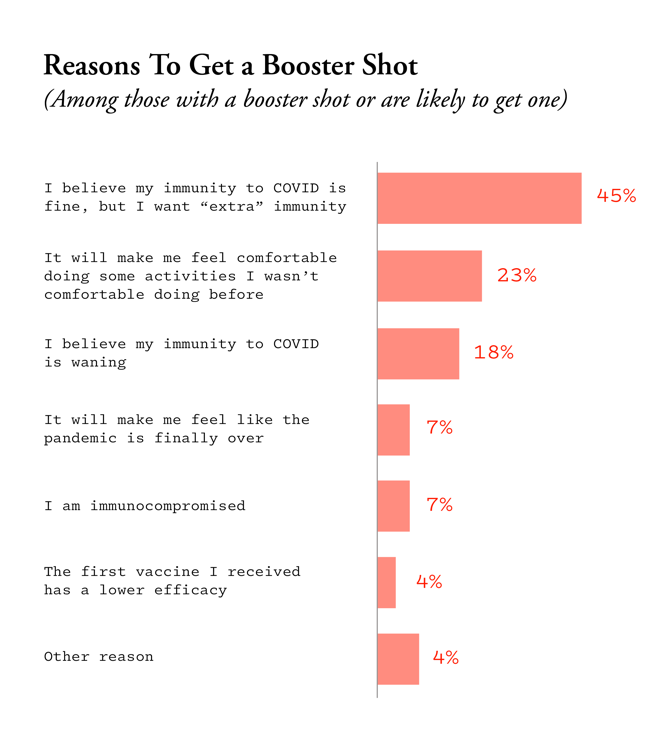

During times of heightened health anxiety, some people will do whatever they can to stay healthy, even if it’s premature or unnecessary. During the 1918 flu, some people died not of the virus but of overdoses of the aspirin they took to treat it. Even in modern times, some people have doubled up on the flu vaccine, says Steven Taylor, a psychologist at the University of British Columbia. “People who are highly worried about their health tend to have greater medical knowledge than the average person,” Taylor told me. These people have not only heard about boosters; they’ve already read a bunch of articles about them and mapped out the nearest booster sites to their house. In our poll, the most common motivator for boosters, selected by 45 percent of respondents, was that though people believe their immunity to COVID-19 is fine, they want “extra” immunity. As Gounder put it, “You have people who think vaccines are great, and if they’re great, one is good, two is better, even more is even better.”

Boosters could also aid the economy. In mid-September, Fauci told Reuters that one motivation for boosters is to reduce the number of “breakthrough” infections among the fully vaccinated. Though two doses of the vaccine may protect against severe disease, boosters might keep more people from testing positive and having to quarantine. “What boosting does is that it increases your antibody levels,” says Larry Corey, a virologist at Seattle’s Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. “The risk perception of going to a restaurant, the risk perception of going to any indoor event or outdoor event will markedly go down because you’re enhancing the vaccine efficacy.” Unlike Gounder, Corey would feel more comfortable going to a baseball game after getting a booster.

He and others say this seems to have played a role in the administration’s thinking about boosters. “President Biden stated this. If you bring the pandemic to an end more quickly, you open up the economy more quickly,” Andy Slavitt, a former adviser to the White House’s COVID-19 response team, told MarketWatch.

Boosters could help the economy even if they don’t immediately reduce breakthrough infections, simply by making some Americans get out more. A quarter of vaccinated respondents in our poll said that getting a booster would change their day-to-day behavior, making them feel more comfortable going on vacation, visiting friends and family, or doing indoor activities with others.

“Boosters are going to be contributing to increased economic activity,” says Tina Dalton, a health-economics professor at Wake Forest University. “More people can go to work; there’s fewer days off of work; people feel more confident about being in the economy.”

Unvaccinated people are driving COVID-19 hospitalizations, but getting people who already like vaccines to get even more vaccines is easier than getting people who refuse vaccines to accept them. Unvaccinated people are “a complicated policy question that is going to involve a lot more than just money to solve,” Dalton told me. “But an easy one is just to put boosters out there. Everyone feels very happy about getting their booster, and you feel like you’re moving the needle.”

Experts will be arguing for months about whether the boosters are truly necessary for younger people, and what the global downsides of focusing extra doses on Americans might be. But they overlook a simple political reality: The boosters aren’t just boosting COVID-19 resistance—they’re boosting morale.