Nearly half a century ago, Roe v. Wade secured a woman’s legal right to obtain an abortion. The ruling has been contested with ever-increasing intensity, dividing and reshaping American politics. And yet for all its prominence, the person most profoundly connected to it has remained unknown: the child whose conception occasioned the lawsuit.

Roe’s pseudonymous plaintiff, Jane Roe, was a Dallas waitress named Norma McCorvey. Wishing to terminate her pregnancy, she filed suit in March 1970 against Dallas County District Attorney Henry Wade, challenging the Texas laws that prohibited abortion. Norma won her case. But she never had the abortion. On January 22, 1973, when the Supreme Court finally handed down its decision, she had long since given birth—and relinquished her child for adoption.

The Court’s decision alluded only obliquely to the existence of Norma’s baby: In his majority opinion, Justice Harry Blackmun noted that a “pregnancy will come to term before the usual appellate process is complete.” The pro-life community saw the unknown child as the living incarnation of its argument against abortion. It came to refer to the child as “the Roe baby.”

Of course, the child had a real name too. And as I discovered while writing a book about Roe, the child’s identity had been known to just one person—an attorney in Dallas named Henry McCluskey. McCluskey had introduced Norma to the attorney who initially filed the Roe lawsuit and who had been seeking a plaintiff. He had then handled the adoption of Norma’s child. But several months after Roe was decided, in a tragedy unrelated to the case, McCluskey was murdered.

Norma’s personal life was complex. She had casual affairs with men, and one brief marriage at age 16. She bore three children, each of them placed for adoption. But she slept far more often with women, and worked in lesbian bars.

Months after filing Roe, Norma met a woman named Connie Gonzales, almost 17 years her senior, and moved into her home. The women painted and cleaned apartments in a pair of buildings in South Dallas. A decade later, in 1981, Norma briefly volunteered for the National Organization for Women in Dallas. Thereafter, slowly, she became an activist—working at first with pro-choice groups and then, after becoming a born-again Christian in 1995, with pro-life groups. Being born-again did not give her peace; pro-life leaders demanded that she publicly renounce her homosexuality (which she did, at great personal cost). Norma could be salty and fun, but she was also self-absorbed and dishonest, and she remained, until her death in 2017, at the age of 69, fundamentally unhappy.

Norma was ambivalent about abortion. She no more absolutely opposed Roe than she had ever absolutely supported it; she believed that abortion ought to be legal for precisely three months after conception, a position she stated publicly after both the Roe decision and her religious awakening. She was ambivalent about adoption, too. Playgrounds were a source of distress: Empty, they reminded Norma of Roe; full, they reminded her of the children she had let go.

Norma knew her first child, Melissa. At Norma’s urging, her own mother, Mary, had adopted the girl (though Norma later claimed that Mary had kidnapped her). Her second child, Jennifer, had been adopted by a couple in Dallas. The third child was the one whose conception led to Roe.

I had assumed, having never given the matter much thought, that the plaintiff who had won the legal right to have an abortion had in fact had one. But as Justice Blackmun noted, the length of the legal process had made that impossible. When I read, in early 2010, that Norma had not had an abortion, I began to wonder whether the child, who would then be an adult of almost 40, was aware of his or her background. Roe might be a heavy load to carry. I wondered too if he or she might wish to speak about it.

Over the coming decade, my interest would spread from that one child to Norma McCorvey’s other children, and from them to Norma herself, and to Roe v. Wade and the larger battle over abortion in America. That battle is today at its most fierce. Individual states have radically restricted the right to have an abortion; a new law in Texas bans abortion after about six weeks and puts enforcement in the hands of private citizens. The Supreme Court, with a 6–3 conservative majority, is scheduled to take up the question of abortion in its upcoming term. It could well overturn Roe.

I had just begun my research when I reached out to Norma’s longtime partner, Connie. She had stood by Norma through decades of infidelity, combustibility, abandonment, and neglect. But in 2009, five years after Connie had a stroke, Norma left her. I visited Connie the following year, then returned a second time. Connie alerted me to the existence of a jumbled mass of papers that Norma had left behind in their garage and that were about to be thrown out. Norma no longer wanted them. I later arranged to buy the papers from Norma, and they are now in a library at Harvard.

Norma had told her own story in two autobiographies, but she was an unreliable narrator. The papers helped me establish the true details of her life. I found in them a reference to the place and date of birth of the Roe baby, as well as to her gender. Tracing leads, I found my way to her in early 2011. Her name has not been publicly known until now: Shelley Lynn Thornton.

I did not call Shelley. In the event that she didn’t already know that Norma McCorvey was her birth mother, a phone call could have upended her life. Instead, I called her adoptive mother, Ruth, who said that the family had learned about Norma. She confirmed that the adoption had been arranged by McCluskey. She said that Shelley would be in touch if she wished to talk.

Until such a day, I decided to look for her half sisters, Melissa and Jennifer. I found and met with them in November 2012, and after I did so, I told Ruth. Shelley then called to say that she, too, wished to meet and talk. She especially welcomed the prospect of coming together with her half sisters. She told me the next month, when we met for the first time on a rainy day in Tucson, Arizona, that she also wished to be unburdened of her secret. “Secrets and lies are, like, the two worst things in the whole world,” she said. “I’m keeping a secret, but I hate it.”

[From the December 2019 issue: Caitlin Flanagan on the dishonesty of the abortion debate]

In time, I would come to know Shelley and her sisters well, along with their birth mother, Norma. Their lives resist the tidy narratives told on both sides of the abortion divide. To better represent that divide in my book, I also wrote about an abortion provider, a lawyer, and a pro-life advocate who are as important to the larger story of abortion in America as they are unknown. Together, their stories allowed me to give voice to the complicated realities of Roe v. Wade—to present, as the legal scholar Laurence Tribe has urged, “the human reality on each side of the ‘versus.’”

When Norma McCorvey became pregnant with her third child, Henry McCluskey turned to the couple raising her second. “We already had adopted one of her children,” the mother, Donna Kebabjian, recalled in a conversation years later. “We decided we did not want another.” The girl born at Dallas Osteopathic Hospital on June 2, 1970, did not join either of her older half sisters. She became instead, with the help of McCluskey, the only child of a woman in Dallas named Ruth Schmidt and her eventual husband, Billy Thornton. Ruth named the baby Shelley Lynn.

Ruth had grown up in a devoutly Lutheran home in Minnesota, one of nine children. In 1960, at the age of 17, she married a military man from her hometown, and the couple moved to an Air Force base in Texas. Ruth quickly learned that she could not conceive. That same year, Ruth met Billy, the brother of another wife on the base. Billy Thornton was a lapsed Baptist from small-town Texas—tall and slim with tar-black hair and, as he put it, a “deadbeat, thin, narrow mustache” that had helped him buy alcohol since he was 15. It had helped him with women, too. Billy had fathered six children with four women (“in that neighborhood,” he told me). Ruth and Billy ran off, settling in the Dallas area.

Years later, when Billy’s brother adopted a baby girl, Ruth decided that she wanted to adopt a child too. The brother introduced the couple to Henry McCluskey. In early June 1970, the lawyer called with the news that a newborn baby girl was available. She was three days old when Billy drove her home. Ruth was ecstatic. “You ain’t never seen a happier woman,” Billy recalled.

McCluskey had told Ruth and Billy that Shelley had two half sisters. But he did not identify them, or Norma, or say anything about the Roe lawsuit that Norma had filed three months earlier. When the Roe case was decided, in 1973, the adoptive parents were oblivious of its connection to their daughter, now 2 and a half, a toddler partial to spaghetti and pork chops and Cheez Whiz casserole.

Ruth and Billy didn’t hide from Shelley the fact that she had been adopted. Ruth in particular, Shelley would recall, felt it was important that she know she had been “chosen.” But even the chosen wonder about their roots. When Shelley was 5, she decided that her birth parents were most likely Elvis Presley and the actor Ann-Margret.

Ruth loved being a mother—playing the tooth fairy, outfitting Shelley in dresses, putting her hair into pigtails. Billy, now a maintenance man for the apartment complex where the family lived in the city of Mesquite, Texas, was present for Shelley in a way he hadn’t been for his other children. When tenants in the complex moved out, he took her with him to rummage through whatever they had left behind—“dolls and books and things like that,” Shelley recalled. When Shelley was 7, Billy found work as a mechanic in Houston. The family moved, and then moved again and again.

Each stop was one step further from Shelley’s start in the world. Mindful of her adoption, she wished to know who had brought her into being: her heart-shaped face and blue eyes, her shyness and penchant for pink, her frequent anxiety—which gripped her when her father began to drink heavily. Billy and Ruth fought. Doors slammed. Shelley watched her mother issue second chances, then watched her father squander them. One day in 1980, as Shelley remembered, “it was just that he was no longer there.” Shelley was 10. A week passed before Ruth explained that Billy would not return.

Shelley found herself wondering not only about her birth parents but also about the two older half sisters her mother had told her she had. She wanted to know them, to share her thoughts, to tell them about her father or about how much she hated science and gym. She began to look hard and long at every girl in every park. She would call town halls asking for information. “I would go, ‘Somebody has to know!’” Shelley told me. “Someone! Somewhere!”

In 1984, Billy got back in touch with Ruth and asked to see their daughter. To be certain that he never came calling, Ruth moved with Shelley 2,000 miles northwest, to the city of Burien, outside Seattle, where Ruth’s sister lived with her husband. It was “so not Texas,” Shelley said; the rain and the people left her cold. But she got through ninth grade, shedding her Texas accent and making friends at Highline High. The next year, she had a boyfriend. He, too, had been adopted. Shelley was happy. She liked attention and got it. “I could rock a pair of Jordache,” she said.

But then life changed. Shelley was 15 when she noticed that her hands sometimes shook. She could make them still by eating. But the tremor would return. She shook when she felt anxious, and she felt anxious, she said, about “everything.” She was soon suffering symptoms of depression too—feeling, she said, “sleepy and sad.” But she confided in no one, not her boyfriend and not her mother. She simply continued on.

Decades after her father left home, it would occur to Shelley that the genesis of her unease preceded his disappearance. In fact, it preceded her birth. “When someone’s pregnant with a baby,” she reflected, “and they don’t want that baby, that person develops knowing they’re not wanted.” But as a teenager, Shelley had not yet had such thoughts. She knew only, she explained, that she wanted to one day find a partner who would stay with her always. And she wanted to become a secretary, because a secretary lived a steady life.

In 1988, Shelley graduated from Highline High and enrolled in secretarial school. One year later, her birth mother started to look for her.

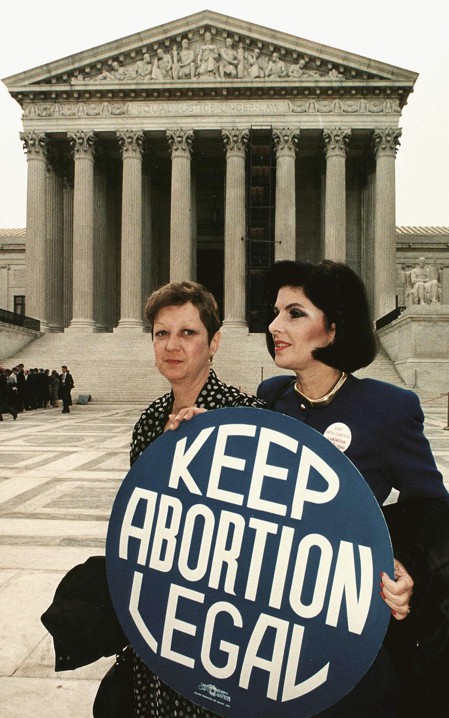

In April 1989, Norma McCorvey attended an abortion-rights march in Washington, D.C. She had revealed her identity as Jane Roe days after the Roe decision, in 1973, but almost a decade elapsed before she began to commit herself to the pro-choice movement. Her name was not yet widely known when, shortly before the march, three bullets pierced her home and car. Norma blamed the shooting on Roe, but it likely had to do with a drug deal. (A woman had recently accused Norma of shortchanging her in a marijuana sale.) Norma landed in the papers. The feminist lawyer Gloria Allred approached her at the Washington march and took her to Los Angeles for a run of talks, fundraisers, and interviews.

Soon after, Norma announced that she was hoping to find her third child, the Roe baby. In a television studio in Manhattan, the Today host Jane Pauley asked Norma why she had decided to look for her. Norma struggled to answer. Allred interjected that the decision was about “choice.” But for Norma it was more directly connected to publicity and, she hoped, income. Some 20 years had passed since Norma had conceived her third child, yet she had begun searching for that child only a few weeks after retaining a prominent lawyer. And she was not looking for her second child. She was seeking only the one associated with Roe.

Norma had no sooner announced her search than The National Enquirer offered to help. The tabloid turned to a woman named Toby Hanft. Hanft died in 2007, but two of her sons spoke with me about her life and work, and she once talked about her search for the Roe baby in an interview. Toby Hanft knew what it was to let go of a child. She had given birth in high school to a daughter whom she had placed for adoption, and whom she later looked for and found. Mother and daughter had “a cold reunion,” Jonah Hanft told me. But a hole in Toby’s life had been filled. And she began working to connect other women with the children they had relinquished. Hanft often relied on information not legally available: Social Security numbers, birth certificates. It was something of an “underworld,” Jonah said. “You had to know cops.” Jonah and his two brothers sometimes helped. Hanft paid them to scan microfiche birth records for the asterisks that might denote an adoption. She charged clients $1,500 for a typical search, twice that if there was little information to go on. And she delivered. By 1989—when Norma went public with her hope to find her daughter—Hanft had found more than 600 adoptees and misidentified none.

Hanft was thrilled to get the Enquirer assignment. She opposed abortion. Finding the Roe baby would provide not only exposure but, as she saw it, a means to assail Roe in the most visceral way. She set everything else aside and worked in secrecy. “This was the one thing we were not allowed to help with,” Jonah said. McCluskey, the adoption lawyer, was dead, but Norma herself provided Hanft with enough information to start her search: the gender of the child, along with her date and place of birth. On June 2, 1970, 37 girls had been born in Dallas County; only one of them had been placed for adoption. Official records yielded an adoptive name. Jonah recalled the moment of his mother’s discovery: “Oh my God! Oh my God! I found her!” From there, Hanft traced Shelley’s path to a town in Washington State, not far from Seattle.

Hanft normally telephoned the adoptees she found. But this was the Roe baby, so she flew to Seattle, resolved to present herself in person. She was waiting in a maroon van in a parking lot in Kent, Washington, where she knew Shelley lived, when she saw Shelley walk by. Hanft stepped out, introduced herself, and told Shelley that she was an adoption investigator sent by her birth mother. Shelley felt a rush of joy: The woman who had let her go now wanted to know her. She began to cry. Wow! she thought. Wow! Hanft hugged Shelley. Then, as Hanft would later recount, she told Shelley that “her mother was famous—but not a movie star or a rich person.” Rather, her birth mother was “connected to a national case that had changed law.” There was much more to say, and Hanft asked Shelley if she would meet with her and her business partner. Shelley took Hanft’s card and told her that she would call. She hurried home.

Two days later, Shelley and Ruth drove to Seattle’s Space Needle, to dine high above the city with Hanft and her associate, a mustachioed man named Reggie Fitz. Fitz had been born into medicine. His great-grandfather Reginald and his grandfather Reginald and his father, Reginald, had all gone to Harvard and become eminent doctors. (The first was a pioneering pathologist who coined the term appendicitis.) Fitz, too, was expected to wear a white coat, but he wanted to be a writer, and in 1980, a decade out of college, he took a job at The National Enquirer. Fitz loved his work, and he was about to land a major scoop.

The answers Shelley had sought all her life were suddenly at hand. She listened as Hanft began to tell what she knew of her birth mother: that she lived in Texas, that she was in touch with the eldest of her three daughters, and that her name was Norma McCorvey. The name was not familiar to Shelley or Ruth. Although Ruth read the tabloids, she had missed a story about Norma that had run in Star magazine only a few weeks earlier under the headline “Mom in Abortion Case Still Longs for Child She Tried to Get Rid Of.” Hanft began to circle around the subject of Roe, talking about unwanted pregnancies and abortion. Ruth interjected, “We don’t believe in abortion.” Hanft turned to Shelley. “Unfortunately,” she said, “your birth mother is Jane Roe.”

That name Shelley recognized. She had recently happened upon Holly Hunter playing Jane Roe in a TV movie. The bit of the movie she watched had left her with the thought that Jane Roe was indecent. “The only thing I knew about being pro-life or pro-choice or even Roe v. Wade,” Shelley recalled, “was that this person had made it okay for people to go out and be promiscuous.”

Still, Shelley struggled to grasp what exactly Hanft was saying. The investigator handed Shelley a recent article about Norma in People magazine, and the reality sank in. “She threw it down and ran out of the room,” Hanft later recalled. When Shelley returned, she was “shaking all over and crying.”

All her life, Shelley had wanted to know the facts of her birth. Having idly mused as a girl that her birth mother was a beautiful actor, she now knew that her birth mother was synonymous with abortion. Ruth spoke up: She wanted proof. Hanft and Fitz said that a DNA test could be arranged. But there was no mistake: Shelley had been born in Dallas Osteopathic Hospital, where Norma had given birth, on June 2, 1970. Norma’s adoption lawyer, Henry McCluskey, had handled Shelley’s adoption; Ruth recalled McCluskey. The evidence was unassailable.

Hanft and Fitz had a question for Shelley: Was she pro-choice or pro-life? “They kept asking me what side I was on,” she recalled. Two days earlier, Shelley had been a typical teenager on the brink of another summer. “All I wanted to do,” she said, “was hang out with my friends, date cute boys, and go shopping for shoes.” Now, suddenly, 10 days before her 19th birthday, she was the Roe baby. The question—pro-life or pro-choice?—hung in the air. Shelley was afraid to answer. She wondered why she had to choose a side, why anyone did. She finally offered, she told me, that she couldn’t see herself having an abortion. Hanft would remember it differently, that Shelley had told her she was “pro-life.”

Hanft and Fitz revealed at the restaurant that they were working for the Enquirer. They explained that the tabloid had recently found the child Roseanne Barr had relinquished for adoption as a teenager, and that the pair had reunited. Fitz said he was writing a similar story about Norma and Shelley. And he was on deadline. Shelley and Ruth were aghast. They hadn’t even ordered dinner, but they hurried out. “We left the restaurant saying, ‘We don’t want any part of this,’” Shelley told me. “ ‘Leave us alone.’” Again, she began to cry. “Here’s my chance at finding out who my birth mother was,” she said, “and I wasn’t even going to be able to have control over it because I was being thrown into the Enquirer.”

Back home, Shelley wondered if talking to Norma might ease the situation or even make the tabloid go away. A phone call was arranged.

The news that Norma was seeking her child had angered some in the pro-life camp. “What is she going to say to that child when she finds him?” a spokesman for the National Right to Life Committee had asked a reporter rhetorically. “‘I want to hold you now and give you my love, but I’m still upset about the fact that I couldn’t abort you’?” But speaking to her daughter for the first time, Norma didn’t mention abortion. She told Shelley that she’d given her up because, Shelley recalled, “I knew I couldn’t take care of you.” She also told Shelley that she had wondered about her “always.” Shelley listened to Norma’s words and her smoker’s voice. She asked Norma about her father. Norma told her little except his first name—Bill—and what he looked like. Shelley also asked about her two half sisters, but Norma wanted to speak only about herself and Shelley, the two people in the family tied to Roe. She told Shelley that they could meet in person. The Enquirer, she said, could help.

Norma wanted the very thing that Shelley did not—a public outing in the pages of a national tabloid. Shelley now saw that she carried a great secret. To speak of it even in private was to risk it spilling into public view. Still, she asked a friend from secretarial school named Christie Chavez to call Hanft and Fitz. The aim was to have a calm third party hear them out. Chavez took careful notes. The news was not all bad: The Enquirer would withhold Shelley’s name. But it would not kill the story. And Hanft and Fitz warned ominously, as Chavez wrote in her neat cursive notes on the conversation, that without Shelley’s cooperation, there was the possibility that a mole at the paper might “sell her out.” After all, they told Chavez, the pro-life movement “would love to show Shelley off” as a “healthy, happy and productive” person.

Ruth turned to a lawyer, a friend of a friend. He suggested that Hanft may have secretly recorded her; Shelley, he said, should trust no one. He sent a letter to the Enquirer, demanding that the paper publish no identifying information about his client and that it cease contact with her. The tabloid agreed, once more, to protect Shelley’s identity. But it cautioned her again that cooperation was the safest option.

Shelley felt stuck. To come out as the Roe baby would be to lose the life, steady and unremarkable, that she craved. But to remain anonymous would ensure, as her lawyer put it, that “the race was on for whoever could get to Shelley first.” Ruth felt for her daughter. “What a life,” she jotted in a note that she later gave to Shelley, “always looking over your shoulder.” Shelley wrote out a list of things she might do to somehow cope with her burden: read the Roe ruling, take a DNA test, and meet Norma. At the same time, she feared embracing her birth mother; it might be better, she recalled, “to tuck her away as background noise.”

Norma, too, was upset. Her plan for a Roseanne-style reunion was coming apart. She decided to try to patch things up. “My darling,” she began a letter to Shelley, “be re-assured that Ms. Gloria Allred … has sent a letter to the Nat. Enquirer stating that we have no intensions of [exploiting] you or your family.” According to detailed notes taken by Ruth on conversations with her lawyer, who was in contact with various parties, Norma even denied giving consent to the Enquirer to search for her child. Hanft, though, attested in writing that, to the contrary, she had started looking for Shelley “in conjunction [with] and with permission from Ms. McCorvey.” The tabloid had a written record of Norma’s gratitude. “Thanks to the National Enquirer,” read a statement that Norma had prepared for use by the newspaper, “I know who my child is.”

On June 20, 1989, in bold type, just below a photo of Elvis, the Enquirer presented the story on its cover: “Roe vs. Wade Abortion Shocker—After 19 Years Enquirer Finds Jane Roe’s Baby.” The “explosive story” unspooled on page 17, offering details about the child—her approximate date of birth, her birth weight, and the name of the adoption lawyer. The story quoted Hanft. The child was not identified but was said to be pro-life and living in Washington State. “I want her to know,” the Enquirer quoted Norma as saying, “I’ll never force myself upon her. I can wait until she’s ready to contact me—even if it takes years. And when she’s ready, I’m ready to take her in my arms and give her my love and be her friend.” But an unnamed Shelley made clear that such a day might never come. “I’m glad to know that my birth mother is alive,” she was quoted in the story as saying, “and that she loves me—but I’m really not ready to see her. And I don’t know when I’ll ever be ready—if ever.” She added: “In some ways, I can’t forgive her … I know now that she tried to have me aborted.”

The National Right to Life Committee seized upon the story. “This nineteen-year-old woman’s life was saved by that Texas law,” a spokesman said. If Roe was overturned, he went on, countless others would be saved too.

Perhaps because the Roe baby went unnamed, the Enquirer story got little traction, picked up only by a few Gannett papers and The Washington Times. But it left a deep mark on Shelley. Having begun work as a secretary at a law firm, she worried about the day when another someone would come calling and tell the world—against her will—who she was.

Shelley was now seeing a man from Albuquerque named Doug. Nine years her senior, he was courteous and loved cars. And from their first date, at a Taco Bell, Shelley found that she could be open with him. When she told Doug about her connection to Roe, he set her at ease: “He was just like, ‘Oh, cool. Or is it not cool? You tell me. I’ll go with whatever you tell me.’”

Eight months had passed since the Enquirer story when, on a Sunday night in February 1990, there was a knock at the door of the home Shelley shared with her mother. She opened it to find a young woman who introduced herself as Audrey Lavin. She was a producer for the tabloid TV show A Current Affair. Lavin told Shelley that she would do nothing without her consent. Shelley felt herself flush, and turned Lavin away. The next day, flowers arrived with a note. Lavin wrote that Shelley was “of American history”—both a “part of a great decision for women” and “the truest example of what the ‘right to life’ can mean.” Her desire to tell Shelley’s story represented, she wrote, “an obligation to our gender.” She signed off with an invitation to call her at Seattle’s Stouffer Madison Hotel.

Ruth contacted their lawyer. “It was like, ‘Oh God!’” Shelley said. “ ‘I am never going to be able to get away from this!’” The lawyer sent another strong letter. A Current Affair went away.

In early 1991, Shelley found herself pregnant. She was 20. She and Doug had made plans to marry, and Shelley was due to deliver two months after the wedding date. She was “not at all” eager to become a mother, she recalled; Doug intimated, she said, that she should consider having an abortion.

Shelley had long considered abortion wrong, but her connection to Roe had led her to reexamine the issue. It now seemed to her that abortion law ought to be free of the influences of religion and politics. Religious certitude left her uncomfortable. And, she reflected, “I guess I don’t understand why it’s a government concern.” It had upset her that the Enquirer had described her as pro-life, a term that connoted, in her mind, “a bunch of religious fanatics going around and doing protests.” But neither did she embrace the term pro-choice: Norma was pro-choice, and it seemed to Shelley that to have an abortion would render her no different than Norma. Shelley determined that she would have the baby. Abortion, she said, was “not part of who I was.”

Shelley and Doug moved up their wedding date. They were married in March 1991, standing before a justice of the peace in a chapel in Seattle. Later that year, Shelley gave birth to a boy. Doug asked her to give up her career and stay at home. That was fine by her. The more people Shelley knew, the more she worried that one of them might learn of her connection to Roe. Every time she got close to someone, Shelley found herself thinking, Yeah, we’re really great friends, but you don’t have a clue who I am.

Despite everything, Shelley sometimes entertained the hope of a relationship with Norma. But she remained wary of her birth mother, mindful that it was the prospect of publicity that had led Norma to seek her out.

At some level, Norma seemed to understand Shelley’s caution, her bitterness. “How could you possibly talk to someone who wanted to abort you?” Norma told one reporter at the time. (That interview was never published; the reporter kept his notes.) But when, in the spring of 1994, Norma called Shelley to say that she and Connie, her partner, wished to come and visit, mother and daughter were soon at odds. Shelley had replied, she recalled, that she hoped Norma and Connie would be “discreet” in front of her son: “How am I going to explain to a 3-year-old that not only is this person your grandmother, but she is kissing another woman?” Norma yelled at her, and then said that Shelley should thank her. Shelley asked why. For not aborting her, said Norma, who of course had wanted to do exactly that. Shelley was horrified. “I was like, ‘What?! I’m supposed to thank you for getting knocked up … and then giving me away.’” Shelley went on: “I told her I would never, ever thank her for not aborting me.” Mother and daughter hung up their phones in anger.

Shelley was distraught. She struggled to see where her birth mother ended and she herself began. She had to remind herself, she said, that “knowing who you are biologically” is not the same as “knowing who you are as a person.” She was the product of many influences, beginning with her adoptive mother, who had taught her to nurture her family. And unlike Norma, Shelley was actually raising her child. She helped him scissor through reams of construction paper and cooled his every bowl of Campbell’s chicken soup with two ice cubes. “I knew what I didn’t want to do,” Shelley said. “I didn’t want to ever make him feel that he was a burden or unloved.”

Shelley gave birth to two daughters, in 1999 and 2000, and moved with her family to Tucson, where Doug had a new job. Thirty years old, she felt isolated, unable to “be complete friends” with anyone, she said. Her depression deepened. She sought help, and was prescribed antidepressants. She decided that she would have no more children. “I am done,” she told Doug.

As the kids grew up, and began to resemble her and Doug in so many ways, Shelley found herself ever more mindful of whom she herself sometimes resembled—mindful of where, perhaps, her anxiety and sadness and temper came from. “You know how she can be mean and nasty and totally go off on people?” Shelley asked, speaking of Norma. “I can do that too.” Shelley had told her children that she was adopted, but she never told them from whom. She did her best to keep Norma confined, she said, “in a dark little metal box, wrapped in chains and locked.”

But Shelley was not able to lock her birth mother away. In the decade since Norma had been thrust upon her, Shelley recalled, Norma and Roe had been “always there.” Unknowing friends on both sides of the abortion issue would invite Shelley to rallies. Every time, she declined.

Norma had come to call Roe “my law.” And, in time, Shelley too became almost possessive of Roe; it was her conception, after all, that had given rise to it. Having previously changed the channel if there was ever a mention of Roe on TV, she began, instead, in the first years of the new millennium, to listen. She began to Google Norma too. “I don’t like not knowing what she’s doing,” Shelley explained.

Shelley then began to look online for her pseudonymous self, to learn what was being written about “the Roe baby.” The pro-life community saw that unknown baby as a symbol. Shelley wanted no part of this. “My association with Roe,” she said, “started and ended because I was conceived.”

Shelley’s burden, however, was unending. She was still afraid to let her secret out, but she hated keeping it in. In December 2012, Shelley began to tell me the story of her life. The notion of finally laying claim to Norma was empowering. “I want everyone to understand,” she later explained, “that this is something I’ve chosen to do.”

In March 2013, Shelley flew to Texas to meet her half sisters—first Jennifer, in the city of Elgin, and then, together with Jennifer, their big sister, Melissa, at her home in Katy. The sisters hugged at Melissa’s front door. They sat down on a couch, none of their feet quite touching the floor. They took in their differences: the chins, for instance—rounded, receded, and cleft, hinting at different fathers. And they took in their similarities: the long shadow of their shared birth mother and the desperate hopes each of them had had of finding one another. Only Melissa truly knew Norma. Jennifer wanted to meet her, and she soon would. Shelley did not know if she ever could.

Their dinner was not yet ready, and the three women crossed the street to a playground. They soared on swings, unaware that happy playgrounds had always made Norma ache for them—the daughters she had let go.

Shelley was still unsure about meeting Norma when, four years later, in February 2017, Melissa let Jennifer and Shelley know that Norma was intubated and dying in a Texas hospital. Shelley was in Tucson. “I’m sitting here going back and forth and back and forth and back and forth,” Shelley recalled, “and then it’s going to be too late.”

Shelley had long held a private hope, she said, that Norma would one day “feel something for another human being, especially for one she brought into this world.” Now that Norma was dying, Shelley felt that desire acutely. “I want her to experience this joy—the good that it brings,” she told me. “I have wished that for her forever and have never told anyone.”

But Shelley let the hours pass on that winter’s day. And then it was too late.

From Shelley’s perspective, it was clear that if she, the Roe baby, could be said to represent anything, it was not the sanctity of life but the difficulty of being born unwanted.

This article has been adapted from Joshua Prager’s new book, The Family Roe: An American Story.