Sign up for The Decision, a newsletter featuring our 2024 election coverage.

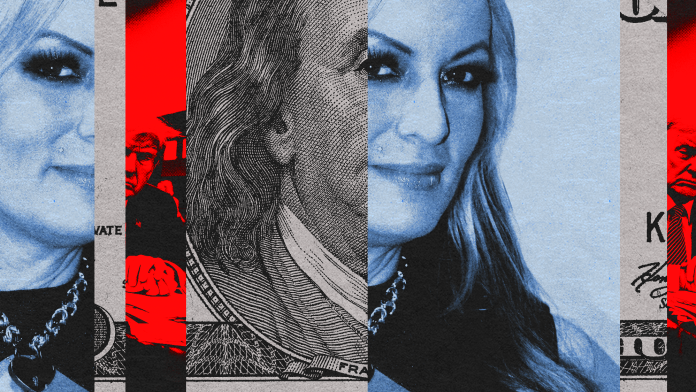

A specter is haunting Donald Trump’s criminal trial in New York state court—the specter of the Access Hollywood tape. The tape does not itself feature in the charges against Trump, which allege that the former president falsified business records as part of covering up a payment to the adult-film actor Stormy Daniels in exchange for her silence over a past sexual encounter. But according to Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, the tape is “centrally relevant” in explaining Trump’s alleged motives behind orchestrating the payment to Daniels. Still, jurors will not hear audio of Trump’s voice bragging about grabbing women by their genitals. Following a ruling by Justice Juan Merchan, prosecutors will be able to introduce evidence of Trump’s notorious comments, but not play the audio itself.

People of the State of New York v. Donald Trump, which is set to begin in earnest today, may well be the only one of the four prosecutions of Trump to go to trial before the 2024 election. In many ways, it’s a strange fit for such a starring role. But its very seediness, encapsulated by the presence of the Access Hollywood tape, is a reminder of both a central controversy of Trump’s 2016 campaign and one of his key sources of appeal as he seeks office again: his contempt for women.

When it comes to Trump’s legal troubles, People v. Trump has always been the odd case out. It doesn’t speak directly to Trump’s attempt to unlawfully hold on to power in 2020, like the cases against Trump in federal court and in Fulton County, Georgia. It’s not as legally straightforward as the charges brought by Special Counsel Jack Smith over Trump’s hoarding of classified documents at Mar-a-Lago after the end of his presidency. When, in March 2023, District Attorney Alvin Bragg became the first prosecutor to announce criminal charges against Donald Trump, the response among the commentariat included no small amount of puzzlement: This case, really, is going first?

[George T. Conway III: The Trump trial’s extraordinary opening]

Thanks to delays that have snarled up the other prosecutions, the New York case is not only the first to produce an indictment, but the first to go to trial. In part because of this newfound political significance, it’s received somewhat of a rebranding in recent months—both from Bragg’s office and from the press, which seems newly inclined to take the case seriously. No longer is it a mere “hush-money case,” as many commentators described it early on. Bragg has now taken to regularly describing it as an “election-interference case,” reasoning that Trump’s alleged scheme to pay Daniels off was aimed at depriving the public of relevant information about a candidate before they cast their votes.

How convinced you are by this reframing may depend, in part, on how compelling you find the legal theory behind the case, which elevates the misdemeanor charge of falsifying business records to a felony by linking it to Trump’s alleged intent to violate both state and federal election law—but without charging those other violations. (Bragg also alleges an intent to commit tax fraud.) At this point, both a federal judge and Justice Merchan have blessed Bragg’s approach to the charges as a matter of law. Still, there’s something at least a little odd about presenting the case as focused on election interference when the underlying campaign-finance issue remains uncharged—and especially when the “election interference” in question is so dramatically less consequential in nature than what happened on and before January 6.

That said, the case does speak to Trump’s willingness to pull dirty tricks during the 2016 campaign, and his last-minute scrambling in the weeks before Election Day. This is where the Access Hollywood tape comes in. After The Washington Post published the tape in October 2016, Bragg has argued, the “defendant and his campaign staff were deeply concerned that the tape would harm his viability as a candidate and reduce his standing with female voters in particular”—hence the willingness to pay Daniels $130,000 for her silence. Along similar lines, Bragg has also sought to introduce material about the allegations of sexual assault and harassment that surfaced against Trump following publication of the Access Hollywood tape. Justice Merchan has not yet reached a decision on this second request.

At this point, the Access Hollywood tape and the ensuing reporting about Trump’s treatment of women have—understandably—faded somewhat into the background, amid all the other scandals. But to read through the court filings from the district attorney’s office is to be plunged back anew into the dizzying chaos of those last few weeks before the 2016 election.

This was a bruising period for many American women, who saw Trump’s casual disregard for their full humanity not just shrugged off but awarded with the country’s highest office. That fury erupted in the massive Women’s March on Washington following Trump’s inauguration in January 2017 and resulted in a surge of political participation and organizing among women. It arguably contributed to the sudden explosion of the #MeToo movement later in 2017. But again and again, it crashed up against Trump’s seeming impunity and lack of care—most bruisingly, in the fall of 2018, when the Republican-led Senate confirmed Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court despite an accusation of attempted sexual assault against him.

[From the January/February 2024 issue: Four more years of unchecked misogyny]

The Stormy Daniels story spanned this period: The Wall Street Journal first reported on the payment to Daniels in January 2018, and Trump’s fixer Michael Cohen pleaded guilty to federal charges involving his role in the hush-money scheme in August of that year. (The question of why the Justice Department has never charged Trump, instead leaving the matter to the district attorney’s office, is one of the lingering strangenesses hanging over the case.) In a March 2018 60 Minutes interview on her 2006 encounter with Trump, Daniels insisted, “This is not a ‘Me Too.’ I was not a victim.” Still, the episode underlines Trump’s relationship with women as fundamentally oriented around expressing his power and authority. Daniels’s own account of their evening together is unsettling; she told 60 Minutes that she did not want to sleep with him and that she did so in part because he suggested that he might give her a slot on The Apprentice. In October of that year, the then-president posted a tweet calling Daniels “horseface.”

These dynamics came up during the jury-selection process. Multiple candidates had participated in the Women’s March. One female prospective juror had posted tweets decrying Trump as “racist” and “sexist”—about which Justice Merchan questioned her while Trump watched from just feet away. Another said that she didn’t closely follow politics, but added, “Obviously, I know about President Trump. I’m a female.” (None of these candidates ultimately made it onto the jury.) Outside the courtroom, meanwhile, a New York Times/Siena poll conducted earlier this month found an astonishing divergence between how men and women view the gravity of the hush-money charges. Women were twice as likely as men to consider the case “very serious,” while men were twice as likely to consider it “not at all serious.”

Understanding People v. Trump in this context is not just an exercise in retreading, once again, the chaos of the 2016 election and of Trump’s first term. It speaks directly to what Trump is offering as a presidential candidate in 2024. As in 2020, campaigning against Joe Biden lends itself less well to the misogynistic aggression that fueled Trump’s run against Hillary Clinton in 2016. This time, though, Trump has built his campaign in part around a promise to force Americans to conform to a sharply restrictive vision of gender and sexuality. As Spencer Kornhaber writes in The Atlantic, Trump’s proposals would “effectively end trans people’s existence in the eyes of the government.” The candidate has also promised to “promote positive education about the nuclear family” and “the roles of mothers and fathers”—and many of his supporters on the right are training their ire on young, single women, a Democratic voting bloc. If Trump’s relationship with Daniels and his treatment of women more generally speak to his understanding of the world as rigidly divided between the dominating man and the women he dominates, then his 2024 campaign is a promise to enforce that vision as a matter of government policy.

In that respect, the New York trial sets up the question nicely, just as the Access Hollywood tape did in 2016: Is this really the kind of man you want to be your president? For many people, of course, the answer was yes. The revelations of Stormy Daniels’s encounter with Trump, which the campaign scrambled so desperately to silence, might not have affected his electoral chances. Will these facts, as explained to the electorate over the course of the trial, make any difference this time around?