This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here.

Usually, you need about 10 minutes to walk from the Rayburn House Office Building to the House Chamber. But if you’re running from a reporter, it’ll only take you five.

When Matt Gaetz spotted me outside his office door one afternoon early last November, he popped in his AirPods and started speed walking down the hall. I took off after him, waving and smiling like the good-natured midwesterner I am. “Congressman, hi,” I said, suddenly wishing I’d worn shoes with arch support. “I just wanted to introduce myself!” I had prepared a long list of questions, hoping for a thoughtful conversation but ready for a tense one. He was a firebrand, after all, or so said the title of his 2020 memoir, Firebrand.

Gaetz is a creature of our time: versed in the art of performance politics and eager to blow up anything to get a little something. He landed in Washington, D.C., as a freshman nobody from the Florida Panhandle, relegated to the back benches of Congress. Seven years later, he’s toppled one House speaker and helped install a new one. He has emerged as the heir of Trumpism. And he’s poised to run for governor in a state of nearly 23 million people.

I had tried repeatedly to schedule an interview with Gaetz. His staff had suggested that he might be willing to sit down with me. But there the firebrand was, that day in November, running away from me in his white-soled Cole Haans. Gaetz broke into a light jog down the escalator, then flew through the long tunnel linking the Rayburn offices to the House Chamber. Finally, I caught up with him at the members-only elevator, my heart pounding. I stretched out my hand. He left it hanging. We got on the elevator together, but he still wouldn’t look at me.

“Are you … afraid of me?” I asked, incredulous. Finally, he made eye contact and glared. Then the doors opened, and he walked out toward the chamber.

Two incidents have defined Gaetz’s tenure in Congress and helped make him a household name. The first was the Department of Justice’s 2020 investigation into whether he had sex with a minor and violated sex-trafficking laws. Gaetz has repeatedly and vehemently denied the claims. That probe was dropped in early 2023, but the House Ethics Committee is still investigating those claims, as well as others—including allegations that Gaetz shared sexual images with colleagues. One video, multiple sources told me, showed a young woman hula-hooping naked. A former Gaetz staffer told me he had watched from the back seat of a van as another aide showed the hula-hooping video to a member of Congress. “Matt sent this to me, and you’re missing out,” the aide had said. (A spokesperson for Gaetz declined to comment for this article, saying that it “contains verifiable errors and laundered rumors” without identifying any. “Be best,” he wrote.)

The investigations seem to have angered and hardened Gaetz. There was a time when he wouldn’t have run away from any reporter. But since the allegations became public, Gaetz has tightened his alliance with the MAGA right, and his rhetoric has grown more cynical. He has become one of the most prominent voices of Trumpian authoritarianism. Warming up the crowd for Donald Trump at the Iowa State Fair last August, Gaetz declared that “only through force do we make any change in a corrupt town like Washington, D.C.”

Gaetz has all the features—prominent brow, bouffant hair, thin-lipped smirk—of an action-movie villain, and at times he’s seemed to cultivate that impression. The second defining event of his time in Congress thus far came in early October, when he filed a motion to kick Kevin McCarthy out of the House speaker’s chair. The motion passed with the help of 208 Democrats and eight Republicans. But not before McCarthy’s allies had each taken a turn at the microphone, defending his leadership and calling Gaetz a selfish, grifting, fake conservative. McCarthy’s supporters had blocked all of the microphones on the Republican side, so Gaetz was forced to sit with the Democrats. A few lawmakers spoke in support of his cause, but mostly Gaetz fought alone: one man against a field of his own teammates.

[Peter Wehner: Kevin McCarthy got what he deserved]

Gaetz didn’t seem to mind. He smiled as he took notes on a legal pad. He displayed no alarm at the fact that every set of eyeballs in the chamber was trained on him, many squinted in rage. He was accustomed to the feeling.

Earlier this week, McCarthy lashed out at Gaetz, telling an interviewer that he’d been ousted from the speakership because “one person, a member of Congress, wanted me to stop an ethics complaint because he slept with a 17-year-old, an ethics complaint that started before I ever became speaker. And that’s illegal, and I’m not gonna get in the middle of it. Now, did he do it or not? I don’t know. But Ethics was looking at it. There’s other people in jail because of it. And he wanted me to influence it.”

In response, Gaetz posted on X: “Kevin McCarthy is a liar. That’s why he is no longer speaker.”

Few items in Gaetz’s biography are more on the nose than the fact that his childhood vacation home—which his family still owns—was the pink-and-yellow-trimmed house along the Gulf of Mexico that was used to film the The Truman Show, the movie about a man whose entire life is a performance for public consumption.

But for most of the year, Gaetz and his family lived near Fort Walton Beach, a part of the Florida Panhandle that’s all white sand and rumbling speed boats—a “redneck riviera,” as one local put it. The area, which now makes up a major part of Gaetz’s congressional district, has a huge military base, and one of the highest concentrations of veterans in the U.S.; it’s also one of the most Republican districts in the country.

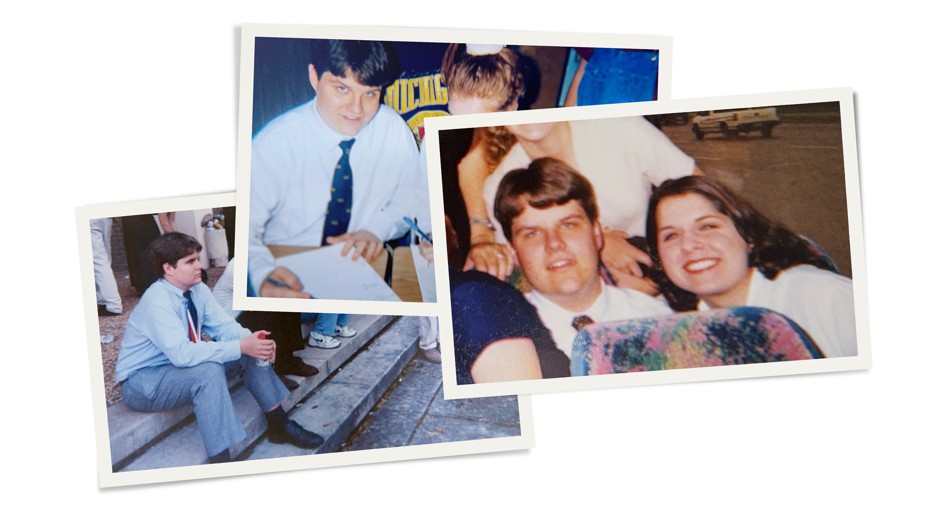

If a person’s identity solidifies during adolescence, then Gaetz’s crystallized inside the redbrick walls of Niceville High School. As a teenager, he was chubby, with crooked teeth and acne. He didn’t have many friends. What he did have was the debate team.

“We tolerated him,” more than one former debate-club member said when I asked about Gaetz. (Most of them spoke with me on the condition of anonymity, citing fear of retribution from Gaetz or his father.) Gaetz could be charming and funny, they told me, but he was also arrogant, a know-it-all. “He would pick debates with people over things that didn’t matter, because he just wanted to,” one former teammate said.

Gaetz also liked to flaunt his family’s wealth. For decades, his father, Don Gaetz, ran a hospice company, which he sold in 2004 for almost half a billion dollars. (The company was later sued by the Department of Justice for allegedly filing false Medicare claims; the lawsuit was settled.) Don was the superintendent of the Okaloosa County School District before being elected to the state Senate in 2006, where he became president. He was a founding member and later chair of the powerful Triumph Gulf Coast board, a nonprofit that doles out funds to local development projects; according to some sources, he still has a heavy hand in it. The counties that make up the panhandle, one lobbyist told me, “are owned by the Gaetzes.”

Matt had a credit card in high school, which was relatively rare in the late 1990s, and he bragged about his “real-estate portfolio,” Erin Scot, a former friend of Gaetz’s, told me. “He was obviously much more well off than basically anyone else, or at least wanted us to think he was.” Once, Gaetz got into an argument with a student who had been accepted to the prestigious Dartmouth debate camp, another classmate said. The fight snowballed until Gaetz threatened to have his father, who was on the school board, call Dartmouth and rescind the student’s application.

Gaetz mostly participated in policy debate. Each year, the National Forensic League announced a new policy resolution—strengthening relations with China, promoting renewable energy—and debaters worked in pairs to build a case both for and against it. To win, debaters had to speak louder, faster, and longer than anyone else. During his senior year, Gaetz won a statewide competition. He wasn’t just good at debate, a former teammate told me: “That was who he was.”

Marilynn McGill, his high-school-debate coach, fondly remembers a teenage Gaetz happily pushing a dolly stacked with bins of evidence on and off the L train in Chicago—and another time dodging snow drifts during a blizzard in Boston. “Matt never complained,” she said. Another year, Gaetz was so eager to attend a tournament in New Orleans that McGill and her husband drove him there with some other debaters in the family RV. “This is the only way to travel, Mr. McGill!” Gaetz shouted from the back.

McGill gushed about her student in our interview. But when I asked what she thought of him now, the former teacher didn’t have much to offer on the record. “He certainly commands the stage still,” she said. “How about that?”

After high school, Gaetz went to Florida State University, where he majored in interdisciplinary sciences, continued debating, and got involved in student government. I had difficulty finding people from Gaetz’s college years who were willing to talk with me; I reached out to old friends and didn’t hear back. Gaetz’s own communications team sent over a list of people I could reach out to; only one replied.

During the summer after his freshman year, Gaetz spent a lot of time at home, hanging out with Scot and some other friends from Niceville. Sometimes, Gaetz would drive them out on his motorboat to Crab Island, where they’d cannonball into the clear, shallow water of the Choctawhatchee Bay. Other days, Gaetz would take them mudding in his Jeep. Somewhere around then, Scot told Gaetz that she was gay, and the revelation didn’t faze him. This meant a lot to her.

Still, Gaetz could get on his friends’ nerves. He referred to one of Scot’s female friends on the debate team using the old Seinfeld insult “man hands.” Once, he noticed peach fuzz on a girl’s face and made fun of her behind her back for having a beard. Gaetz would occasionally offer unsolicited advice on how his friends should respond if they were ever pulled over on suspicion of drunk driving: Refuse to take a Breathalyzer test. Chug a beer in front of the officer to make it more difficult to tell if they’d been drinking earlier in the night. It was immature kid stuff, Scot said. “Most of us grew out of it. He made a career of it.”

After graduating from FSU in 2003, Gaetz enrolled at William and Mary Law School in Virginia. Unlike his classmates, who rented apartments with roommates or lived in campus housing, property records show that Gaetz bought a two-story brick Colonial with a grand entranceway and white Grecian columns in the sun room. It was the ultimate bachelor pad: a maze of high-ceilinged rooms for weekend ragers, with a beer-pong table and a kegerator, according to one former law-school acquaintance. Back then, the acquaintance said, Gaetz had a reputation for bragging about his sexual conquests.

The last time Scot saw Gaetz was at a friend’s wedding in March 2009, two years after he’d graduated from law school and one year into what would be a very short-lived gig as an attorney at a private firm in Fort Walton Beach. By that point, Gaetz had already started planning his political career, which would begin, officially, a few months later with a special-election bid for the state House. Also by that point, Gaetz had been arrested on charges of drunk driving after leaving a nightclub on Okaloosa Island called the Swamp. He’d followed his own advice and refused a Breathalyzer test. (Prosecutors ultimately dropped the charges, and Gaetz’s license was reinstated after only a few weeks.)

At the wedding, Scot was eager to catch up with Gaetz. A photo from the night of the rehearsal dinner shows Gaetz, in a cream-colored suit jacket, wrapping his arm around her. She was excited to show him a picture of her girlfriend, whom he’d never met. She says that later, at the bar, Gaetz passed around an image of his own: a cellphone photo of a recent hookup, staring up topless from his bed.

There used to be a restaurant called the 101 on College Avenue in Tallahassee, just steps from the state capitol. Customer favorites included happy-hour martinis and buffalo-chicken pizza. Gaetz and his buddies in the legislature would hold court there after votes, friends and colleagues from that time told me.

Gaetz had been elected to the state House, after raising almost half a million dollars—including $100,000 of his own money, and support from MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough, who had formerly represented the district and was a friend of the Gaetzes. In the general election, Gaetz defeated his Democratic opponent by more than 30 points; he would go on to run unopposed for a full term in 2010, in 2012, and again in 2014.

During this period, a group of young Republican lawmakers partook in what several of my sources referred to as the “Points Game,” which involved earning points for sleeping with women (and which has been previously covered by local outlets). As the journalist Marc Caputo has reported, the scoring system went like this: one point for hooking up with a lobbyist, three points for a fellow legislator, six for a married fellow legislator, and so on. Gaetz and his friends all played the game, at least three people confirmed to me, although none could tell me exactly where Gaetz stood on the scoreboard. (Gaetz has denied creating, having knowledge of, or participating in the game.)

At the time, Don Gaetz was president of the Florida Senate, and the father-and-son pair was referred to, mostly behind their backs but sometimes to their faces, as Daddy Gaetz and Baby Gaetz. The latter had a tendency to barge in on his father’s meetings, hop on the couch, and prop his feet up, Ryan Wiggins, a former political consultant who used to work with Matt Gaetz, told me. Because of their relationship, Matt “had a level of power that was very, very resented in Tallahassee,” she said.

Gaetz wasn’t interested in his father’s traditional, mild-mannered Republicanism, though. Like any good Florida conservative, the younger Gaetz was a devoted gun-rights supporter and a passionate defender of the state’s stand-your-ground law. As chair of the state House’s Finance and Tax Committee, he pushed for a $1 billion statewide-tax-cut package. But Gaetz talked often about wanting the GOP to be more modern: to acknowledge climate change, to get younger people involved. Toward that end, he sometimes forged alliances with Democrats. “If you went and sat down with him one-on-one,” said Steve Schale, a Democratic consultant who worked with Gaetz in the state legislature, “he could be very likable.”

Schale, who had epilepsy as a child, was happy to see Gaetz become one of a handful of Republicans to support the Charlotte’s Web bill, which legalized a cannabis extract for epilepsy treatment. Gaetz also befriended Jared Moskowitz, a Democrat who is Gaetz’s current colleague in Congress, when they worked together to pass a bill strengthening animal-cruelty laws. “You could go into his office and say, ‘Hey man, I think you’re full of shit on that,’” Schale said. “And he’d say, ‘All right, tell me why.’ I kinda liked that.”

Gaetz seemed to relish the sport of politics—the logistics of floor debates and the particulars of parliamentary procedure. He argued down his own colleagues and tore up amendments brought by both parties. Sometimes friends would challenge Gaetz to a game: They’d give him a minute to scan some bill he wasn’t familiar with, one former colleague told me, and then make him riff on it on the House floor.

Gaetz had a knack for calling attention to himself. He would take unpopular positions, sometimes apparently just to make people mad. He was one of two lawmakers to vote against a state bill criminalizing revenge porn. And even when his own Republican colleague proposed reviewing Florida’s stand-your-ground law after the killing of Trayvon Martin, Gaetz said he refused to change “one damn comma” of the legislation.

Plus, “he understood the power of social media before almost anyone else,” Peter Schorsch, a publisher and former political consultant, told me. Gaetz was firing off inflammatory tweets and Facebook posts even in the early days of those apps. All of it was purposeful, by design, the people I spoke with told me—the debating, the tweeting, the attention getting. Gaetz was confident that he was meant for something bigger. “The goal then,” Schorsch said, “was to be where he is now.”

In 2015, while Donald Trump was descending the golden Trump Tower escalator, Gaetz was halfway through his third full term in the Florida House, pondering his next move. His father would retire soon from the Florida Senate, and Gaetz had already announced his intention to run for the seat. But then Jeff Miller, the Republican representative from Gaetz’s hometown district, decided to leave Congress.

Gaetz had endorsed former Florida Governor Jeb Bush in the GOP primary. (“I like action, not just talk. #allinforjeb,” he’d tweeted in August 2015.) But by March, Bush had dropped out. Left with the choice of Trump, Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, or then–Ohio Governor John Kasich, Gaetz embraced the man he said was best suited to disrupt the stale workings of Washington, D.C.

In the same statement announcing he was running for Congress, Gaetz declared that he was #allin for Trump.

At first, Gaetz was miserable in Congress. Almost a year after being elected, at 34—he’d defeated his Democratic opponent by almost 40 points—Gaetz complained about his predicament to Schale. He’d never dealt with being a freshman member on the backbench. “He hated everything about it,” Schale told me.

In Gaetz’s telling, the money turned him off most. Given the makeup of his district, he wanted to be on the Armed Services Committee. But good committee assignments required donations: When Gaetz asked McCarthy about it, the majority leader advised that he raise $75,000 and send it to the National Republican Congressional Committee, Gaetz wrote in Firebrand. He sent twice that much to the NRCC, he wrote, and made it onto both the Armed Services and the Judiciary Committees. But he claimed to be disgusted by the system.

During those first miserable months, Schale wondered how his colleague would handle his newfound irrelevance. “I would’ve told you he’d do one of two things: He would either retire or he was going to light himself on fire,” Schale told me. “He chose to light himself on fire.”

It can take years to rise up through the ranks of a committee, build trust with colleagues, and start sponsoring legislation to earn the kind of attention and influence that Gaetz craved. He wanted a more direct route. So his team developed a strategy: He would circumvent the traditional path of a freshman lawmaker and speak straight to the American people.

This meant being on television as much as possible. Gaetz went after the most hot-button cultural issue at the time: NFL players kneeling for the anthem. “We used that as our initial hook to start booking media,” one former staff member told me. One of his early appearances was a brief two-question interview with Tucker Carlson. Though Carlson mispronounced his name as “Getts” (it’s pronounced “Gates”), the congressman spoke with a brusque confidence. “Rather than taking a knee, we ought to see professional athletes taking a stand and actually supporting this country,” he said.

From there, the TV invites flooded in. Gaetz would go on any network to talk about anything as long as the broadcast was live and he knew the topic ahead of time. He had become a loud Trump defender—introducing a resolution to force Special Counsel Robert Mueller to resign and even joining an effort to nominate Trump for the Nobel Peace Prize. A white board in his office displayed a list of media outlets and two columns of numbers: how many hits Gaetz wanted to do each week at any given outlet and how many he’d already completed. Around his office, he liked to quote from one of his favorite movies, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, in a faux southern accent: “We ain’t one-at-a-timin’ here. We’re mass communicating!’’

Soon, the president was calling. Trump asked Gaetz for policy advice, and suggested ways that Gaetz could highlight the MAGA agenda on television. Sometimes, when the president rang and Gaetz wasn’t near the phone, his aides would sprint around the Capitol complex looking for him, in a race against Trump’s short attention span, another former staffer told me. Gaetz claimed in his book that he once even took a call from Trump while “in the throes of passion.”

With his new influence, Gaetz helped launch Ron DeSantis’s political career. In 2017, he urged Trump to endorse DeSantis for Florida governor. At the time, DeSantis was struggling in the Republican primary, but after receiving Trump’s approval, he shot ahead. DeSantis made Gaetz a top campaign adviser.

[From the May 2023 issue: How freedom-loving Florida fell for Ron DeSantis]

Gaetz would occasionally travel with the president on Air Force One, writing mini briefings or speeches on short notice. Trump was angry when Gaetz voted to limit the president’s powers to take military action, but the two worked it out. “Lincoln had the great General Grant … and I have Matt Gaetz!” Trump told a group of lawmakers at the White House Christmas party in 2019, according to Firebrand.

The two had a genuine relationship, people close to Gaetz told me. From his father, Gaetz had learned to be cunning and competitive. But he was never going to be a country-club Republican. “He’s aspirationally redneck,” said Gaetz’s friend Charles Johnson, a blogger and tech investor who became famous as an alt-right troll. (Johnson once supported Trump but says he now backs Joe Biden.) Trump, despite his wealth and New York upbringing, “is the redneck father Matt never had,” Johnson told me.

HBO’s The Swamp, a documentary that chronicled the efforts of a handful of House Republicans agitating for various reforms, takes viewers behind the scenes of Gaetz’s early months in Congress, when he lived in his office and slept four nights a week on a narrow cot pushed into a converted closet. Gaetz is likable in the documentary, coming off as a cheerful warrior and a political underdog. But the most striking moment is when he answers a call from President Trump, who praises him for some TV hit or other. When Gaetz hangs up the phone, he is beaming. “He’s very happy,” Gaetz tells the camera, before looking away, lost in giddy reflection.

Gaetz has positioned himself as a sort of libertarian populist. He’s proposed abolishing the Environmental Protection Agency, but he’s not a climate-change denier, and has supported legislation that would encourage companies to reduce carbon emissions voluntarily. He has consistently opposed American intervention in foreign wars, and he advocates fewer restrictions on marijuana possession and distribution. He still allies himself with Democrats when it’s convenient: He defended a former colleague, Democratic Representative Katie Hill, when she was embroiled in a revenge-porn scandal and forged an unlikely alliance with Democrat Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez over their desire for a ban on congressional stock trading.

In his book, Gaetz argues that too many members of Congress represent entrenched special interests over regular people, and too much legislation is the result of cozy relationships between lawmakers and lobbyists. In 2020, he announced that he was swearing off all federal PAC money. (It has always been difficult, though, to take Gaetz’s yearning for reform seriously when his political idol is Trump, a man who not only refused to divest from his own business interests as president but who promised to “drain the swamp” before appointing a staggering number of lobbyists to positions in his government).

Gaetz’s personal life began making headlines for the first time in 2020. That summer, the 38-year-old announced, rather suddenly, that he had a “son” named Nestor Galban, a 19-year-old immigrant from Cuba. Gaetz had dated Galban’s older sister May, and when the couple broke up, Galban moved in and had lived with him since around 2013. “Though we share no blood, and no legal paperwork defines our family relationship, he is my son in every sense of the word,” Gaetz wrote in his book.

Later in 2020, Gaetz met a petite blonde named Ginger Luckey at a party at Mar-a-Lago. Luckey, who is 12 years younger than Gaetz, grew up in Long Beach, California, and works for the consultancy giant KPMG. In the early days of their relationship, she was charmingly naive about politics, Gaetz wrote in his book: During one dinner with Fox’s Tucker Carlson, Luckey was excited to discover that Carlson hosted his own show. “What is it about?” she’d asked.

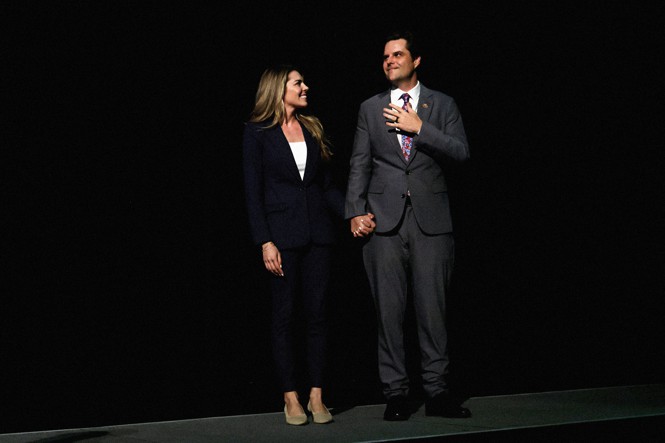

Luckey is hyper-disciplined and extremely type A, “the kind of person who will get you out of bed to work out whether you like it or not,” Johnson said. Luckey tweets about sustainable fashion and avoiding seed oils, and she softens Gaetz’s sharp edges. She longboards and sings—once, she kicked off a Trump book-release party with a delicate rendition of “God Bless America.” Gaetz asked Luckey to marry him in December 2020 on the patio at Mar-a-Lago. When she said yes, Trump sent over a bottle of champagne.

Three months later, in late March 2021, news broke that the Department of Justice was looking into allegations that Gaetz had paid for sex with women in 2018. One claim held that Gaetz’s friend, the Florida tax collector Joel Greenberg, had recruited women online and had sex with them before referring them to Gaetz, who slept with them too. But the most serious allegation was that Gaetz had had sex with a girl under the age of 18, and had flown her to the Bahamas for a vacation. By the time Gaetz proposed to Luckey, the FBI had reportedly confiscated his phone.

Gaetz has denied paying for sex or engaging in sex with a minor. But Greenberg would go on to be charged with a set of federal crimes and ultimately plead guilty to sex trafficking a child. On April 6, The New York Times reported that Gaetz had requested a blanket pardon from the Trump White House in the final weeks of his administration, which was not granted.

Other sordid claims have spilled out since. “He used to walk around the cloakroom showing people porno of him and his latest girlfriend,” one former Republican lawmaker told me. “He’d show me a video, and I’d say, ‘That’s great, Matt.’ Like, what kind of a reaction do you want?” (The video, according to the former lawmaker, showed the hula-hooping woman.) Cassidy Hutchinson, the former Trump White House aide, wrote in her memoir that Gaetz knocked on her cabin door one night during a Camp David retreat and asked Hutchinson to help escort him back to his cabin. (Gaetz has denied this.)

On social media, people called Gaetz a pedophile and a rapist; commenters on Luckey’s Instagram photos demanded to know how she could possibly date him. In many political circles, Gaetz became untouchable. He was “radioactive in Tallahassee,” one prominent Florida Republican official told me, and for a while, he stopped being invited on Fox News. Around this time, DeSantis cut Gaetz out of his inner circle. His wife, Casey, had “told Ron that he was persona non grata,” Schorsch told me. “She hated all the sex stories that came out.” (Others have suggested that Gaetz fell out with DeSantis after a power struggle with the governor’s former chief of staff.)

The ongoing House Ethics Committee investigation could have further consequences for Gaetz. The committee may ultimately recommend some kind of punishment for him—whether a formal reprimand, a censure, or even expulsion from Congress—to be voted on by the whole House.

Gaetz’s response to the investigation has been ferocious denial. He has blamed the allegations on a “deep state” plot or part of an “organized criminal extortion” against him. His team blasted out emails accusing the left of “coming” for him. But privately, in the spring of 2021, Gaetz was despondent. He worried that Luckey would call off their engagement. “She’s for sure going to leave me,” Johnson said Gaetz told him in the days after the stories broke.

But Luckey didn’t leave. In a series of TikToks posted that summer, one of her sisters called Gaetz “creepy” and “a literal pedophile.” “My estranged sister is mentally unwell,” Luckey told The Daily Beast in response.

Gaetz and Luckey married in August of 2021, earlier than they’d planned. It was a small ceremony on Catalina Island, off the coast of Los Angeles. On the couple’s one-year anniversary, Luckey posted a picture of the two of them in the sunshine on their wedding day, Luckey in a low-cut white dress and Gaetz in a gray suit. “Power couple!!” then-Representative Madison Cawthorn wrote. Below, someone else commented, “He’s using you girl.”

Rather than cowing him, the allegations seemed to give Gaetz a burst of vengeful energy. He tightened his inner circle and leaned harder than ever into the guerilla persona he’d begun to develop. No longer welcome in many greenrooms, Gaetz became a regular on Steve Bannon’s War Room podcast before launching a podcast of his own. He set off on an America First Tour with the fellow Trump loyalist Marjorie Taylor Greene. The two traveled state to state, alleging widespread fraud in the 2020 presidential election and declaring Trump the rightful president of the United States. People from both parties now viewed Gaetz as a villain. It was as if Gaetz thought, Why not go all in?

Republicans faced disappointing results in the 2022 midterm elections, and by the time January rolled around, their slim House majority meant that each individual member had more leverage. In January 2023, Gaetz took advantage, leading a handful of Republican dissidents in opposing Kevin McCarthy’s ascendance to the speakership. He and his allies forced McCarthy to undergo 14 House votes before they finally gave in on the 15th round. Things were so tense that, at one point, Republican Mike Rogers of Alabama lunged at Gaetz and had to be restrained by another member. But Gaetz had gotten what he’d wanted. Among other concessions, McCarthy had agreed to restore a rule allowing a single member to call for a vote to remove the speaker. It would be McCarthy’s downfall.

In October, Gaetz strode to the front of the House Chamber and formally filed a motion to oust his own conference leader. McCarthy had failed to do enough to curb government spending and oppose the Democrats, Gaetz told reporters. He announced that McCarthy was “the product of a corrupt system.” As a government shutdown loomed, the 41-year-old Florida Republican attempted an aggressive maneuver that had never once been successful in the history of Congress: using a motion to vacate the speaker of the House. Twenty-four hours later, McCarthy was out.

Ultimately, the evangelical MAGA-ite Mike Johnson of Louisiana was chosen as the Republicans’ new leader. With the election of Johnson, Gaetz had removed a personal foe, skirted the establishment, and given Trumpism a loud—and legitimate—microphone. “The swamp is on the run,” Gaetz said on War Room. “MAGA is ascendant.” This had been Gaetz’s plan all along, Bannon told me afterward. In January 2023, he had been “setting the trap.” Now he was executing on his vision. Gaetz had ushered in a new “minoritarian vanguardism,” Bannon told me, proudly. “They’ll teach this in textbooks.”

Gaetz has options going forward. If the former president is reelected in November, Gaetz “could very easily serve in the Trump administration,” Charles Johnson told me. But most people think Gaetz’s next move is obvious: He’ll leave Congress and run for governor of Florida in 2026. Even though he’s publicly denied his interest in the job, privately, Gaetz appears to have made his intentions known. “I am 100 percent confident that that is his plan,” one former Florida Republican leader told me. Gaetz looks to be on cruise control until then, committed to making moves that will please the MAGA base and set him up for success in two years.

The Republican field in Florida is full of potential gubernatorial primary candidates. Possible rivals for Gaetz include Representative Byron Donalds, state Attorney General Ashley Moody, and even Casey DeSantis. But in Florida, Gaetz is more famous than all of them, and closer to the white-hot center of the MAGA movement. If he gets Trump’s endorsement, Gaetz could have a real shot at winning the primary and, ultimately, the governor’s mansion.

On October 24, Mike Johnson spoke at a press conference after being nominated for speaker. He hadn’t been elected yet, but everyone knew he had the votes. Flanked by grinning lawmakers from across the spectrum of his party—Steve Scalise, Elise Stefanik, Lauren Boebert, and Nancy Mace—he promised a “new form of government” that would quickly kick into gear to serve the American people. Johnson’s colleagues applauded when he pledged to stand with Israel, and they booed together, jovially, when a reporter asked about Johnson’s attempts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election.

Watching on my computer at home, I couldn’t find Gaetz right away. But then the C-SPAN camera zoomed out and there he was, in the back, behind cowboy-hat-wearing John Carter of Texas. I had to squint to see Gaetz. He looked small compared with the others, in his dark suit and slicked-back hair. Once, he stood on his tiptoes to catch a glimpse of the would-be speaker, several rows ahead.

Despite his very central role in Johnson’s rise, Gaetz had been relegated to the far reaches of the gathering, behind several of his colleagues who had strongly opposed removing McCarthy. But Gaetz didn’t seem to mind. He clapped with the rest of them, and even pumped his fist in celebration. Most of the time, his mouth was upturned in a slight smile. He was in the back now, but he wouldn’t be there long.