Sign up for The Decision, a newsletter featuring our 2024 election coverage.

Senator Shelley Moore Capito, Republican of West Virginia, officially endorsed Donald Trump’s campaign for reelection two Saturdays ago. The news landed as an afterthought, which is probably how she intended it. “Today at the @WVGOP Winter Meeting Lunch, I announced my support for President Donald Trump,” Capito wrote on X, as if she were making a dutiful entry in a diary.

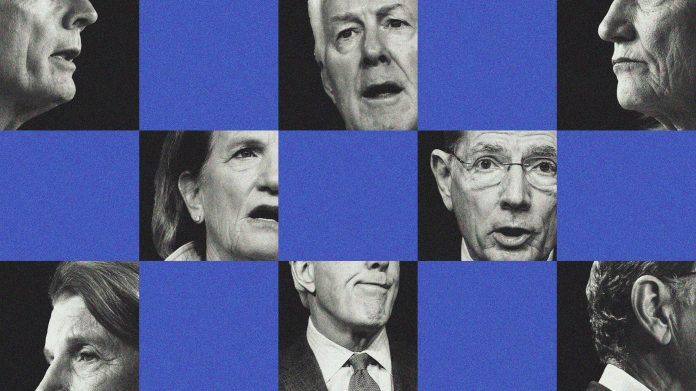

Republicans have reached the point in their primary season, even earlier than expected, when the party’s putative leaders line up to reaffirm their allegiance to Trump. Several of Capito’s Senate colleagues joined the validation brigade around the same time: the GOP’s second- and third-ranking members, John Cornyn of Texas and John Barrasso of Wyoming, along with Trump’s long-ago rivals Ted Cruz of Texas and Marco Rubio of Florida. None of their endorsements caused much of a ripple. Perhaps some mischief-maker surfaced the old video of Cruz calling Trump “a sniveling coward” in 2016 or Rubio calling him “the most vulgar person ever to aspire to the presidency.” But for the most part, the numbing shows of conformity felt inevitable, just as Trump’s third straight presidential nomination now appears to be.

The GOP once prided itself on being an alliance of free-thinking frontiersmen who embraced rugged individualism, a term popularized by Republican President Herbert Hoover. This is no longer that time. Full acquiescence to Trump is now the most essential Republican “ethic,” such as it is, or at least the chief prerequisite to viability in the party. This near-total submission to the former boss has persisted no matter how egregious his actions are or how plainly he states his authoritarian goals.

[David A. Graham: The GOP completes its surrender]

Yet the Republican Party now appears to have entered a new level of capitulation to Trump: a kind of ho-hum acceptance phase, where slavish devotion has become almost mundane, like joining a grocery line. There’s a certain power in bland and seemingly harmless gestures from people who know better. Permission structures strengthen over time. Complicity calcifies in obscurity.

It’s natural to focus on the more blatant markers of Trump’s domination and his facilitators’ dereliction. You can scoff at the clownish stunts of sycophancy shown by the Ramaswamy-Scott-Stefanik wing of the hippodrome. Or marvel at the prevailing silence that greeted Trump’s vow to suspend the Constitution or the legal finding that he was liable for sexual abuse. Or be amazed by the swiftness with which Republican lawmakers reversed course this week on a bipartisan border bill, which many of them had demanded, simply because Trump insisted it die.

In a sense, though, the innocuous statements from the periphery, such as Capito’s post, are more stupefying.

Capito, 70, served seven terms in the House before being elected to the Senate in 2014. She has earned a reputation as a serious, relatively moderate lawmaker, and has forged a host of bipartisan alliances. She is the fifth-ranked senator in Republican leadership and is the ranking member on the Senate environment committee.

The daughter of a three-term governor of West Virginia, Capito was born into the status of “Republican in good standing,” something she has worked throughout her long career to maintain. This also makes her a classic “Republican who knows better.”

Like many of her GOP colleagues, Capito has expressed serious unease with Trump in the past. She said she “felt violated as an American” by the January 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol by Trump’s supporters, which she called an “incredibly traumatic” experience. She voted against convicting Trump in the Senate impeachment trial over the riot but made a point of saying it was only because he was not in office anymore (“My ‘no’ vote today is based solely on this constitutional belief”). In general, Capito deemed Trump’s conduct after the 2020 election to be “disgraceful” and declared in a statement that “history will judge him harshly.”

Capito, it turns out, would not.

[Read: Why Republican politicians do whatever Trump says]

Although she did not expect Trump to be the Republican nominee again—“I don’t think that’s going to happen,” she said in October 2021—Capito is now fully on board with his restoration. Her endorsement on January 27 carried an almost nostalgic longing for Trump’s time in the White House. “Our economy thrived, our nation was secure, and we worked to address the challenges at our border,” she wrote. Sure, Trump wasn’t perfect, but what’s a little violation, trauma, or national disgrace? Apparently it still beats the alternative, Nikki Haley.

Capito’s office declined a request for comment.

This is not meant to single out Shelley Moore Capito for special cowardice or delinquency. Okay, maybe it is meant to single her out a little, but mostly as an object lesson in the insidious complicity of going along merely by adding one’s name to a stockpile. (Trump had yet to receive a single endorsement from a Senate Republican at this point in the campaign eight years ago: Jeff Sessions of Alabama became the first, on February 28, 2016.)

Capito illustrates the power of the random. She could be any number of Republican officeholders. When he quit the presidential race last month, Chris Christie mentioned some others. “Look at what’s happening just in the last few days,” Christie, the former New Jersey governor, said in his exit speech, taking note of high-level elected Republicans who were falling into line. He singled out Barrasso and House Whip Tom Emmer of Minnesota.

Barrasso and Emmer are “good people who got into politics, I believe, for the right reasons,” Christie said in his speech. They are both well-mannered institutionalists who have been flayed by the former president in the past: Trump dismissed Barrasso as Mitch McConnell’s “flunky” and “rubber stamp,” and torpedoed Emmer’s bid to replace Kevin McCarthy as speaker of the House, deriding him as a “Globalist RINO.” Barrasso and Emmer would probably rather their party moved on from Trump.

And yet, they endorsed him. “They know better,” Christie said. “I know they know better.” From direct experience, in Christie’s case: He endorsed Trump in 2016 for what he now admits were purely political reasons. He then embarked on a long and at times debasing stint as one of Trump’s chief political butlers during his presidency.

[Read: The most pathetic men in America]

In his speech last month, Christie said his biggest frustration with the GOP primary was that so many Republican officials and candidates complain privately about Trump yet remain loath to condemn him in public. (Of course, many Democrats engage in a similar dance about President Joe Biden and his age, expressing fulsome delight in public that he’s running for reelection at 81—he has the energy of a 35-year-old!—while moaning endlessly in private about how old he seems.)

Shared tolerance for conduct like Trump’s tends to build over time. “People are more likely to accept the unethical behavior of others if the behavior develops gradually (along a slippery slope),” according to a 2009 article in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, which was quoted by my colleague Anne Applebaum in her 2020 Atlantic cover story, “History Will Judge the Complicit.”

“What’s just astounding to me is that there are so few outliers,” Eric S. Edelman, a former U.S. ambassador to Turkey and a Pentagon official in the George W. Bush administration, told me. Edelman, a career foreign-service officer, is a friend of the Cheney family and a fervent critic of Trump.

“I know that ambition in Washington is kind of a garden-variety sin, right?” Edelman said. Partisan considerations are inevitable, he added, “but by and large, the people I saw in Washington, whether I thought their policies were good or bad, on some level you expected them to be animated by what’s best for the nation.”

Pioneers, by definition, are outliers. Republicans from Theodore Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan to Donald Trump were first viewed by their party as rogues or extremists. But the main driver for most politicians is almost always longevity, Mark Sanford, a former Republican representative from and governor of South Carolina, told me. “It’s to stay in the game for as long as you can, which is really the opposite of leadership,” said Sanford, who himself was an outlier—an anti-Trump Republican—which essentially cost him his job in Congress (he was defeated in a Republican primary in 2018). “Leadership is, I believe, This is my true north; I’m going to stand where I’m going to stand.”

Edelman quoted a line attributed to Ted Cruz in 2016, after Trump had defeated him in a bitter nomination fight, smearing the senator’s wife and father in the process. Cruz famously refused to endorse Trump at the Republican National Convention that year. “History isn’t kind to the man who holds Mussolini’s jacket,” Cruz told friends, according to an account by my colleague Tim Alberta in his 2019 book, American Carnage.

Cruz has since become a chief accessory to Trump in a party lousy with jacket-holders for the former president.

I remember being in Cleveland on the night Cruz gave his mutinous convention speech. It was a stirring and gutsy performance, the first (and last) time I’d ever felt much admiration for him. The bloodlust in the hall was palpable as it became clear that he was not building to any endorsement. “Vote your conscience” was Cruz’s crescendo line, which aroused the loudest boos of the night. They lingered like a warning siren, and if Cruz ignored it at the time, he has heeded it ever since. Add him to the list.