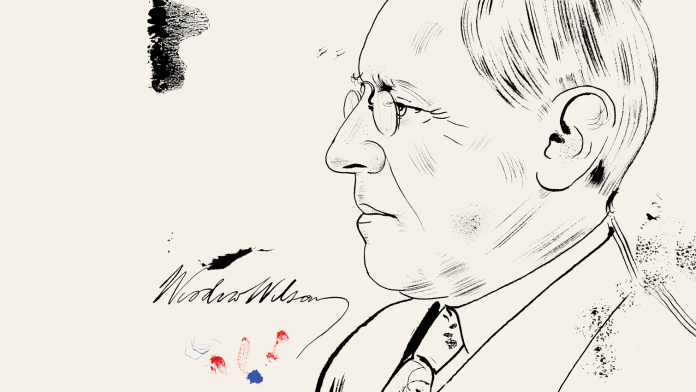

February marks a century since the death of Woodrow Wilson. Of all America’s presidents, none has suffered so rapid and total a reversal of reputation.

Wilson championed—and came to symbolize—progressive reform at home and liberal internationalism abroad. So long as those causes commanded wide support, Wilson’s name resonated with the greats of American history. In our time, however, the American left has subordinated the causes of reform and internationalism to the politics of identity, while the American right has rejected reform and internationalism altogether. Wilson’s standing has been crushed in between.

In 1948, and again in 1962, surveys of American historians rated Wilson fourth among American presidents, lagging behind only Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Wilson’s fellow presidents esteemed him too. Harry Truman wrote, “In many ways, Wilson was the greatest of the greats.” Richard Nixon admired Wilson even more extravagantly. He hung Wilson’s portrait in his Cabinet room, and used as his personal desk an antique that he believed—mistakenly, it turns out—had been used by Wilson.

Arthur S. Link, who edited 69 volumes of Wilson’s papers and wrote five volumes of biography, paid Wilson this tribute: “Aside from St. Paul, Jesus and the great religious prophets, Woodrow Wilson was the most admirable character I’ve ever encountered in history.”

Yet over the past half decade, Wilson’s name has been scrubbed from schools and memorials across the country. Wilson’s own Princeton, which he elevated from mediocrity to greatness in his eight years as university president, has removed his name from its school of public policy and a dormitory. “We have taken this extraordinary step,” the university announced in June 2020, “because we believe that Wilson’s racist thinking and policies make him an inappropriate namesake for a school whose scholars, students, and alumni must be firmly committed to combatting the scourge of racism in all its forms.”

These acts of obloquy are endorsed across the spectrum of liberal and progressive opinion. The New York Times editorial board had urged the renaming and damned Wilson as “an unrepentant racist.” In his recent history, American Midnight, the eminent liberal writer Adam Hochschild accuses Wilson of culpability for the unjust imprisonment, illegal abuse, and outright murder of trade unionists and anti-war dissenters. Here at The Atlantic, the historian Timothy Naftali described Wilson as “an awful man who presided over an apartheid system in the nation’s capital.”

[Tim Naftali: The worst president in history]

Unlike other historical figures criticized by American progressives, such as Robert E. Lee and Christopher Columbus, Wilson has found few countervailing defenders among American conservatives. If anything, contemporary conservatives revile Wilson even more than progressives do.

The columnist George Will spices his speeches with a favorite joke about Wilson’s trajectory from the loser in an academic fight at Princeton to the president who “ruined the 20th century.” In his 2007 book, Liberal Fascism, Jonah Goldberg (then an editor at National Review) condemned Wilson as “the twentieth century’s first fascist dictator.” Glenn Beck regularly fulminated against Wilson on his Fox News show in the early 2010s. Beck called Wilson an “evil SOB” and a “dirtbag racist.” He summed up: “I hate this guy. I don’t even want to show his picture.”

Anti-Wilson animus has even swayed the conservative jurists of the U.S. Supreme Court. In 2022, the Court delivered a ruling in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency that dramatically curtailed greenhouse-gas regulations in the United States. To support his concurrence with the decision, Justice Neil Gorsuch devoted a footnote entirely to damning Wilson as an antidemocratic bigot. Wilson was one of the first American scholars to study the emerging administrative state, and conservatives like Gorsuch imagine that if they can discredit him, they can discredit it as well—and doom environmental regulations by association.

Wilson’s bigotries were very real. As a historian, he made the case that freedmen had too hastily been given the franchise following the Civil War. All his life, he accepted a subordinate status for Black Americans. As a politician, he enforced and extended it. In private, he told demeaning jokes in imitated dialect and delighted in minstrel shows. He was said to have praised D. W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation—originally titled The Clansman—as “like writing history with lightning,” though this at least is almost certainly untrue: Wilson viewed the movie in silence, according to a witness at the time. He may have been annoyed because an inter-title within the movie quoted Wilson’s A History of the American People as seeming to praise the Ku Klux Klan. The relevant section had in fact rebuked the Klan for its lawless violence. But Wilson objected only to the Klan’s means, not its ends. He wholeheartedly endorsed the extinguishing of Reconstruction-era reforms by state legislatures and white-dominated courts.

[From the December 2023 issue: What The Atlantic got wrong about Reconstruction]

Wilson’s bigotries were shared by his predecessors and immediate successors in the presidency. In his 1909 inaugural address, William Howard Taft repudiated equal voting rights for Black Americans and justified the exclusion of immigrants from China. Taft’s predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt, enthusiastically promoted the pseudoscience of racial hierarchy that placed white Europeans at the top. The segregation of the federal civil service that Wilson’s administration instituted was maintained by the four presidents who followed him: Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, and FDR.

My point is not to acquit Wilson of the charges against him, nor to minimize those charges by blaming the times, rather than him. Historical figures are responsible for their beliefs, words, and actions. But if one man is judged the preeminent villain of his era for bigotries that were common among people of his place, time, and rank, that singular fixation demands explanation. Why Wilson rather than Taft or Coolidge?

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that Wilson must be brought low because he stood so high. He is scorned now because of our weakening attachment to what was formerly regarded as good and great.

Here’s the story that once would have been told about Wilson by the liberal-minded.

After winning the presidential election of 1912, Wilson broke four decades of conservative domination of U.S. politics to lead the most dramatic social-reform program since the 1860s.

He and his party’s majority in both houses of Congress lowered the tariffs that had loaded the cost of government onto working people. In place of those high tariffs, Wilson and the Democrats enacted an income tax, a first step toward a more redistributive fiscal policy in the United States—and among the gravest of his sins in the eyes of conservative critics.

They also gave the U.S. a central banking system, the Federal Reserve, to counter the deflationary effect of the gold standard, which often favored lenders at the expense of borrowers. They ensured that the Fed would represent the interests of the public, and not be controlled by large private banks, as many Republicans of the day preferred. They introduced the first federal regulation of wages and hours in the United States. Wilson and his congressional majority passed laws against abusive corporate practices and created the Federal Trade Commission to enforce those laws.

Wilson supported women’s suffrage during his presidency. He opposed alcohol prohibition, albeit with less success. He twice vetoed literacy tests for immigrants, which were an early harbinger of the ethnically discriminatory immigration restrictions of the 1920s. He nominated the first Jew to serve on the Supreme Court, Louis Brandeis. (Earlier, as governor of New Jersey, Wilson had also appointed the first Jew to that state’s supreme court.) After the U.S. entered the First World War, Wilson’s administration nationalized the country’s railway system. It simplified the route network, streamlined operations, and improved pay and working conditions in the huge and crucial industry—then rapidly returned the rails to private ownership.

Wilson’s most impressive innovations came in the realm of foreign affairs. He granted substantial autonomy to the Philippines, America’s largest colonial possession, and opened a path to full independence. Wilson negotiated payment to Colombia for the loss of Panama in a revolution that had been fomented by Theodore Roosevelt. He resisted military intervention in the Mexican Revolution, and he tried to mediate a negotiated end to World War I. When at last forced into that war, Wilson sought a generous and enduring peace for all of the combatants. He put his hopes in the League of Nations; even if that project largely failed, it paved the way for the more successful forms of collective security created after 1945. Sumner Welles, perhaps FDR’s most trusted foreign-policy adviser, wrote in 1944 that Wilson’s vision of world order had excited his own generation “to the depths of our intellectual and emotional being.”

Even at the zenith of Wilson’s repute, his most sophisticated admirers attached important caveats to their story. Wilson had wanted to stay out of the war in Europe. He failed. He then tried to negotiate peace. He failed again. His commitment to self-determination did not apply to the small countries of this hemisphere: A U.S. intervention he ordered in Haiti in 1914 extended into a 20-year occupation.

Wilson’s admirers also could not deny that each of those failures was in great part his own fault. In his earlier academic writings, Wilson had praised compromise and concession. As president, his early concessions to white southerners cost him the support of some northern African Americans who had flipped from the Republican Party to back him in 1912. One of those who endorsed Wilson was W. E. B. Du Bois. The next year, Du Bois lamented his decision in an editorial for The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP: “Not a single act and not a single word of yours since election has given anyone reason to infer that you have the slightest interest in the colored people or desire to alleviate their intolerable position.” Wilson met with disillusioned Black former supporters once in 1913, then again in 1914. That second meeting ended in a rare eruption of Wilson’s temper. He ordered his visitors out of his office and never received them again. As he settled into the presidency, Wilson became more rigid, more convinced of his own righteousness and his adversaries’ wickedness.

[From the May 1993 issue: Wilson Agonistes]

Wilson’s offenses multiplied after a disabling stroke in 1919. He clung to office, barely able to move or communicate, his condition concealed by his wife and his doctor. (The Twenty-Fifth Amendment, ratified in 1967, offered a solution to the Wilson problem—a president who cannot do his job but will not resign.) Many of the darkest acts of his administration occurred during this period of feebleness: mass deportations of foreign-born political radicals; passivity in the face of the murderous anti-Black pogroms that flared across America’s big cities; a de facto granting of permission to the most repressive and reactionary tendencies in U.S. society.

In the era of liberal academic hegemony, historians sought to weigh Wilson’s errors and misdeeds against his administration’s accomplishments, reaching a range of conclusions. But that era has closed. We live now in a more polarized time, one of ideological extremes on both left and right. Learned Hand, a celebrated federal judge of Wilson’s era, praised “the spirit which is not too sure that it is right.” Our contemporaries have exorcised that spirit. We are very sure that we are right. We have little tolerance for anyone who seems in any degree wrong.

In our zeal, we refuse to understand past generations as they understood themselves. We expect them to have organized their mental categories the way we organize ours—and we are greatly disappointed when we discover that they did not.

Today, we tend to think of economic and racial egalitarianism as closely yoked causes. One hundred years ago, this was far from the case. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of those Americans most skeptical of corporate power were also the most hostile to racial equality, while those Americans who most adamantly rejected economic reform hoped to mobilize racial minorities as allies.

The leading proponent of racial segregation in Wilson’s administration was his postmaster general, a Texan named Albert Sidney Burleson. Before 1913, about 4,000 of the Post Office’s more than 200,000 employees were Black. Burleson dismissed Black postmasters across the South. At postal headquarters, in Washington, D.C., he grouped the facility’s seven Black clerks together and screened them off from white employees. Burleson segregated dining rooms and bathrooms too. When the U.S. declared war against Germany, Burleson used his powers to bar dissenting magazines and newspapers from the mail, for most small periodicals their only way to reach their audiences—no hearings, no appeals, just his whim and will.

From this sorry history, you might infer that Burleson was an all-around reactionary. But no.

Elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1898, Burleson immediately showed himself to be a progressive and a reformer. He fiercely opposed the use of federal injunctions against striking trade unionists. He advocated for lower tariffs and a redistributive income tax. He rejected the gold standard. Burleson and his wife, Adele, were ardent proponents of women’s suffrage in the state of Texas. One of their daughters, Laura, was elected to the Texas legislature in 1928, only the fourth woman to reach that chamber.

The seeming contradiction between Burleson the white supremacist and Burleson the social reformer recurred again and again in Wilson’s administration. Wilson’s Navy secretary, Josephus Daniels, was an even more virulent racist than Burleson. As a newspaper editor in Raleigh, Daniels incited the 1898 insurrection that crushed the vestiges of Black political rights in North Carolina. Daniels supported railroad regulation and greater investment in public education. FDR would later appoint him ambassador to Mexico. In that post, Daniels opposed U.S. action to undo the Mexican nationalization of the oil industry and sympathized with the anti-Franco side of the Spanish Civil War.

The disconnect between race and reform operated in reverse, too. Wilson’s most effective and hated political rival was Henry Cabot Lodge, the leader of the Senate Republicans after 1918. Lodge was in most respects deeply conservative: a champion of corporate prerogatives, the gold standard, and high tariffs. Lodge, an enthusiastic imperialist, had called for the annexation of the Philippines and Puerto Rico. Lodge despised and distrusted the new immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. When 11 Italian immigrants were lynched in New Orleans in 1891, he published an article justifying and excusing the crime. Yet Lodge was also the author and lead sponsor of an important 1890 House bill to protect Black voting rights in the South, the last such effort in Congress until the modern civil-rights era.

In the time of Woodrow Wilson, issues and ideas were clustered very differently from today. Champions of Black political rights could display bitter animosity toward Catholic immigrants. Many exponents of women’s suffrage also held racist views. Some defenders of labor rights also supported bans on teaching evolution. Heroes of free academic inquiry were fascinated by the project of eugenics. Early advocates of sexual autonomy were attracted to fascism or communism or—as George Bernard Shaw was—both.

What are you to do with this information once you have it? The leading men and women of America’s past were frequently tainted by bigotries and misjudgments that appear repulsive now. Yet if repulsion is all we feel, we do a great injustice both to them and to ourselves. The good and great country that you inhabit today was inherited from imperfect leaders such as Wilson, as uncomfortable as that may make some on the left. And the gradual progress that the U.S. has made since 1787 has all depended on the respect Wilson and other leaders had for the original plan, as much as some on the right insist that they betrayed it. Demand that Americans preserve their collective past unchanged, and you doom the whole structure to decay and ultimate collapse. Teach Americans to despise their collective past, and their future will hold only a struggle for power, pitting group against group, without rules or restraints.

“It would be the irony of fate if my administration had to deal chiefly with foreign affairs.” Woodrow Wilson spoke those famous words to a friend shortly before his inauguration. That irony of fate of course came true.

Wilson is one of the very few presidents to have bequeathed an ism. There is no Washingtonism, there is no Lincolnism, there is no Rooseveltism, but there is “Wilsonianism.” Wilsonianism is almost universally regarded in a negative light—as, at worst, bad and dangerous or, at best, sweetly naive but sadly unrealistic.

But Wilson was far from naive. He grew up in the ruined landscape of the post–Civil War South. His prepresidential writing often cautioned against too much confidence in human beings and too much certainty about human institutions.

[From the April 1886 issue: Woodrow Wilson on responsible government under the Constitution]

In his message to Congress on April 2, 1917, when he called for a declaration of war, Wilson insisted that “the world must be made safe for democracy.” Modern-day Americans commonly interpret those words as a vow to convert the whole world to democracy. What Wilson meant, however, was that the nation could no longer hope to find security in the “detached and distant situation” of its geographic location, as Washington described it in his farewell address. The United States had grown too big; distances of time and space had narrowed too much for it to be unaffected by the actions of once-remote countries. The menace to “peace and freedom,” Wilson saw, “lies in the existence of autocratic governments backed by organized force which is controlled wholly by their will, not by the will of their people.” Not all nations would or could be democratic, but from then on, American peace and freedom would be safeguarded not by geography but by “a partnership of democratic nations.”

Recoiling from Wilson’s vision of mutual international benefit, many of his present-day critics yearn for a foreign policy that relies on dominating a small number of client states and ignoring the rest of the world from behind border walls and trade protections.

People who take this view call themselves “America First,” perhaps unaware that Wilson himself seized the phrase as a campaign slogan in 1916 to condemn both the ethnic lobbies he regarded as too pro-German and the industrial and financial interests he mistrusted as too pro-Allies. In the 1930s and early ’40s, the slogan was appropriated by the isolationists and Axis sympathizers of the America First Committee. The outrage of Pearl Harbor and the horror of Auschwitz then discredited “America First” for a long time—but not forever.

Now, in the 21st century, we see the strange sight of political partisans using Wilson’s own “America First” phrase to attack Wilson’s highest ideals. In February 2023, one of the harshest critics of U.S. support for democratic Ukraine spoke at the Heritage Foundation. At the core of Senator Josh Hawley’s remarks was an attack on Wilson:

Woodrow Wilson, as you may remember, was a dedicated internationalist. He was a dedicated globalist on principle, by the way. I mean, he thought that “we should make the world safe for democracy.” That was his line that he famously used. And I think what you saw is after the Cold War, you had a whole generation of American policy makers who said the Wilsonian moment has now arrived. Borders don’t matter. American uniqueness doesn’t matter. We’re going to make all of the world more like America and we’re going to make America more like the world and there’ll be this great global integration.

Wilson believed almost none of those things. What Wilson did believe was that American security had become inseparable from the security of others, and that American power would be accepted only if guided by universal values. Wilson argued this case most explicitly in a January 1918 address to Congress. The speech is famous for the 14 points he enumerated as U.S. war aims. But more important than any specific aim was the logic undergirding them all:

What we demand in this war, therefore, is nothing peculiar to ourselves. It is that the world be made fit and safe to live in; and particularly that it be made safe for every peace-loving nation which, like our own, wishes to live its own life, determine its own institutions, be assured of justice and fair dealing by the other peoples of the world as against force and selfish aggression. All the peoples of the world are in effect partners in this interest, and for our own part we see very clearly that unless justice be done to others it will not be done to us.

Wilson was the first world leader to perceive security as a benefit that could be shared by like-minded nations. Until then, each great power had clambered over others to field bigger armies, float bigger navies, and accumulate more colonies. This competition had culminated in the disastrous outbreak of the Great War. Wilson glimpsed the possibility of a different way: that shared values might provide a more stable basis for peace among advanced nations than the quest for military dominance.

Only the U.S. possessed the wealth and power to make the vision work. Tragically, neither the U.S. nor the world was ready for this vision in Wilson’s lifetime. The president himself lacked the skill, expertise, and tact to realize it. But the vision lay dormant, waiting for a future chance.

[From the December 1902 issue: Woodrow Wilson on the ideals of America]

I am not personally a thorough admirer of Wilson’s. A famous quip attributed to Winston Churchill (about another political moralist) might have applied to Wilson’s austere personality: “He has all the virtues I dislike and none of the vices I admire.” An evening with Theodore Roosevelt would have been fun, but most of us would have wished to bid an early good night to Wilson—especially once he’d revealed that his favorite form of humor was mildly smutty limericks.

Wilson’s bigotry was as chilly as his wit. He started his teaching career at Bryn Mawr. One of his associates there, the daughter of an abolitionist minister, remarked to an early biographer that Wilson was the first southern white man she’d ever met with no personal warmth for any individual Black person.

Wilson’s tariff, banking, and regulatory reforms were driven more by a quest for rationality and efficiency than by empathy and compassion. The British Liberal governments that held power from 1905 to the outbreak of World War I introduced that country’s first old-age pensions and unemployment insurance. In the United States, broad programs of social insurance would have to await the New Deal of the 1930s.

As a war leader, Wilson deferred absolutely to professional soldiers’ advice, even though those soldiers had learned their trade in small wars against weak enemies. That approach cost many American lives when the top U.S. military commander, John Pershing, rebuffed British and French efforts to teach American troops the painful lessons they had learned from prior years of Western Front experience. Americans went into battle in 1918 still using the human-wave tactics that had cost the British and French so dearly.

Wilson’s gravest failures were in his chosen mission as a peacemaker. As the former U.S. diplomat Philip Zelikow details in his damning book The Road Less Traveled, Wilson personally bungled a real opportunity to reach peace in the second half of 1916. All of the principal combatants yearned for such a peace, but none dared be the first to ask for it. All were looking for the U.S. to lead, as it had led the peace negotiations after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05. Wilson fatally hesitated to apply such leadership, nor did he delegate the task to anybody who might have succeeded.

When the war instead ended with the German collapse in 1918, Wilson never grasped or even paid much attention to the problems of postwar economic recovery, domestic or international. He was a man of ideas and ideals, not one of ledgers and accounts; of words, not numbers. The United States plunged into a severe economic depression in 1920. War-scarred and hungry Europe suffered even more. Voters emphatically rejected Wilson’s party in the 1920 elections.

The Republican congressional majorities of the 1920s returned to the high-tariff policies of the 19th century, dooming any hope that Germany, Britain, France, Belgium, Italy, and other former combatants might export their way to economic normality. Instead, the United States insisted on collecting war debts from former allies. To repay the U.S., the former allies were left no choice but to squeeze Germany for reparations. To finance reparations, Germany massively borrowed from U.S. private-sector lenders. This cycle of tariff-driven debt helped set in motion the catastrophe of the Great Depression.

The post-Wilson Democrats bitterly split along regional and cultural lines. It took them 103 ballots to nominate a presidential candidate at their convention in New York City in 1924. The Republicans would win that year’s election decisively, and 1928’s too, by running against Wilson’s war and the depression that followed. Only after another war, even more terrible than the one that came before it, was Wilson’s foreign-policy legacy at last rehabilitated. As Americans and their allies developed institutions of collective security, free trade, and global governance after 1945, Wilson’s best ideals were realized at last.

This is the Wilson who remains to this day the founder and definer of American world leadership. Henry Kissinger, who despised Wilson and (I suspect) inwardly hoped to displace his intellectual primacy, ultimately had to admit in his 1994 book, Diplomacy : “It is above all to the drumbeat of Wilsonian idealism that American foreign policy has marched since his watershed presidency, and continues to march to this day.” I very much believe that the United States has been a force for good in the world in the 20th and 21st centuries. If you do also, then our appreciation must begin with the foundational achievement of the president who first exerted that force.

You do not need to withhold any single criticism of Woodrow Wilson, the man and the president, to regret the harm done by the unbalanced and totalizing censure that has been heaped upon him over the past decade. Wilson was a great domestic reformer. He was the first American president to perceive and explain how American power could anchor the peace of a future democratic world.

His ideas and ideals still undergird American foreign policy at its most generous and successful. His words still reverberate more than a century later, long after those of his contemporary critics have lapsed into obscurity. When the United States rallies to the defense of Ukraine against Russian invasion or of Guyana against Venezuelan threats, when it seeks peace through free-trade agreements and joins with allies to deter aggression, it is speaking in the language originally chosen by Woodrow Wilson.

So how should we comprehend the people of bygone times when their principles and prejudices diverge from those that now prevail? In a speech delivered in 1896, Wilson declared:

Nothing is easier than to falsify the past. Lifeless instruction will do it. If you rob it of vitality, stiffen it with pedantry, sophisticate it with argument, chill it with unsympathetic comment, you render it as dead as any academic exercise … Your real and proper object, after all, is not to expound, but to realize it, consort with it, and make your spirit kin with it, so that you may never shake the sense of obligation off.

Modern America owes just such an obligation to Wilson. He showed the way to the modern world. He did not reach his hoped-for destination, but neither yet have we. Cancel Wilson, and you empower those who seek to discredit the high goals for which he worked. Those are goals still worth working toward. To realize them, supporters of American global leadership cannot dispense with the practical and moral legacy of Woodrow Wilson.

Acknowledge his flaws and failures. Then restore Wilson’s name to the places of honor from which it was hastily and wrongly purged.

This article appears in the March 2024 print edition with the headline “In Defense of Woodrow Wilson.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.