Editor’s Note: This article is part of “On Reconstruction,” a project about America’s most radical experiment.

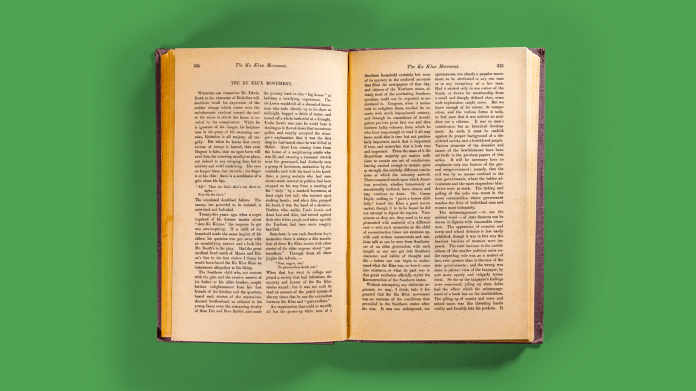

The last time The Atlantic decided to reckon with Reconstruction in a sustained way, its editor touted “a series of scholarly, unpartisan studies of the Reconstruction Period” as “the most important group of papers” it would publish in 1901.

That was true, as far as it went. The collection of essays assembled by Bliss Perry, the literature professor who had recently taken the magazine’s reins, was a tribute to the editor’s craft. The contributors were evenly split between northerners and southerners, and included Democrats and Republicans, participants and historians, professors and politicians. One had been a Confederate colonel, another a Union captain. The prose was as vivid as the perspectives seemed varied.

Yet “The Reconstruction Papers,” as they were billed, were equally an indictment of the journalistic conceit of balance. Perry prided himself on the diversity of the voices he featured in his magazine. “It is not to be expected that they will agree with one another,” he once wrote. “Perhaps they will not even, in successive articles, agree with themselves.” That was a noble vision, but the forum he convened fell well short of the ideal. Despite their disagreements, on the most crucial points, the authors of his Reconstruction studies shared the common views of the elite class to which nearly all of them belonged—and much of what they wrote was both morally and factually indefensible.

The first essay came from Perry’s old Princeton colleague Woodrow Wilson—or “My dear Wilson,” as Perry addressed him. Wilson, then a prominent political scientist, focused on the constitutional legacies of the era—he believed Congress had overstepped its role by protecting civil rights—but slipped in a broad critique of the enterprise. “The negroes were exalted; the states were misgoverned and looted in their name,” he wrote, until “the whites who were real citizens got control again.”

“It’s pretty much the plot of The Birth of a Nation,” Kate Masur, a historian at Northwestern University, told me. She meant that literally. D. W. Griffith’s flamboyantly racist film adapted quotes from the future president’s monumental A History of the American People, in which he expanded on the story he’d sketched in The Atlantic.

The last essay in the collection came from William A. Dunning, a Columbia University historian. The work of his students—who became known as the Dunning School—would promote the view that Black people were incapable of governing themselves, and that Reconstruction had been a colossal error. Dunning portrayed the end of Reconstruction as a reversion to the natural order, with Jim Crow enforcing “the same fact of racial inequality” that slavery had once encoded.

What came in between Wilson and Dunning was somehow even worse. One contributor lauded slavery for lifting “the Southern negro to a plane of civilization never before attained by any large body of his race” by teaching him to be “law-abiding and industrious,” and lamented that emancipation had encouraged idleness. Another wrote an apology for the Ku Klux Klan. Perhaps its murderous violence couldn’t quite be excused, he allowed, but the restoration of white supremacy was still “clearly worth fighting for” and “unattainable by any good means.” How could a magazine founded on the eve of the Civil War by abolitionists, which had fervently championed Reconstruction as it unfolded, ever have published such tripe?

The simplest answer is that, by 1901, many elite Americans had soured on the messiness of democracy. In the North, they met the surge of immigrants into industrial cities with creative efforts—civil-service reforms, independent commissions—to take power out of voters’ hands. Out West, they persecuted Chinese immigrants and excluded them from citizenship. In the South, they were busily amending state constitutions to strip Black voters of their rights and to enshrine Jim Crow. And in the territories that America had just acquired in the Spanish-American War, they were building an empire by force of arms. The old sectional divides could be healed, they found, through a new consensus—that only well-educated, propertied white men were capable of governing themselves, and that it was folly to give anyone else the chance to try.

The essays on Reconstruction fit snugly within this consensus, finding that its fatal flaw had been an excess of democracy. To a man (and they were all men), their authors agreed that granting newly emancipated Black men the right to vote had been a terrible mistake, producing corrupt governments that took from the propertied classes to support the poor. The debate was limited to why the mistake had happened, and how it could best be undone.

Except, that is, for one extraordinary contribution. Perry selected a rising star in the world of sociology, W. E. B. Du Bois, to write about the Freedmen’s Bureau—the federal agency that had been charged with protecting the formerly enslaved. But Du Bois, the sole Black author invited to take part, had larger ambitions. The first and last lines of his essay were identical: “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.” In between, he sketched a vision of Reconstruction as an incomplete revolution, one that had accomplished much before its untimely end left the work for future generations to complete. “Despite compromise, struggle, war, and struggle,” he wrote, “the Negro is not free.”

[From the March 1901 issue: W. E. B. Du Bois on the Freedmen’s Bureau]

Not many magazines of the era, the historian Gregory Downs told me, would have given him the assignment. “It signals a surprising openness to engagement and argument,” he said. In fact, Du Bois failed to interest The Century, perhaps the nation’s preeminent magazine, in an ambitious article on Reconstruction. The Atlantic helped introduce him to a national audience, and although it was the first time he tackled the subject, it would not be the last. His 1935 opus, Black Reconstruction, became the foundation on which our modern understanding of the era is built.

After the last essay, Perry appended a dispirited note. The gravest error of Reconstruction, he conceded, had been “the indiscriminate bestowal of the franchise upon the newly liberated slaves.” But he hastened to add that, unlike most of his essayists, he objected only to the pace of enfranchisement, not to the ultimate goal. The Atlantic, Perry wrote, still believed “in the old-fashioned American doctrine of political equality, irrespective of race or color or station.”

Today, the essays Perry gathered are of interest mostly as windows into a distant era. If there is a useful lesson to take from the Wilsons and the Dunnings, it lies not in any insights they purported to offer, but in their delusions of objectivity. They wrote their history as a just-so story, an explanation of why they deserved the privileges they enjoyed while others were better suited for subservient stations. Du Bois, by contrast, looked to the past not to justify present-day hierarchies but to understand them, and to explore abandoned alternatives. The problem with America, he concluded, wasn’t that democracy and equality had gone too far, but that they had not gone nearly far enough.

Perry’s note closed by voicing his hope that “the old faith that the plain people, of whatever blood or creed, are capable of governing themselves” would eventually reassert itself. Today, at a moment when the old faith is faltering again, we might wish the same.

This article appears in the December 2023 print edition with the headline “The Atlantic and Reconstruction.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.