President Joe Biden’s core foreign-policy argument has been that his steady engagement with international allies can produce better results for America than the impulsive unilateralism of his predecessor Donald Trump. The eruption of violence in Israel is testing that proposition under the most difficult circumstances.

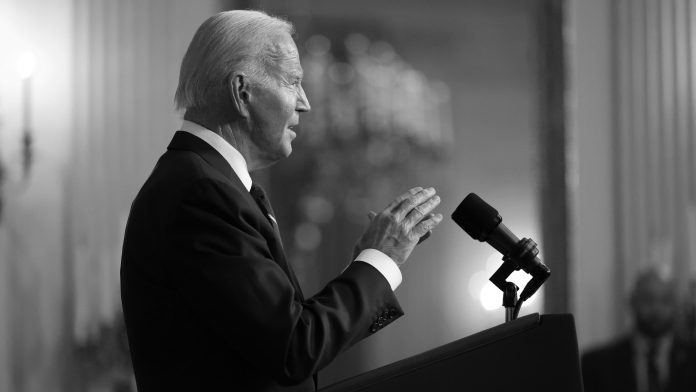

The initial reactions of Biden and Trump to the attack have produced exactly the kind of personal contrast Biden supporters want to project. On Tuesday, Biden delivered a powerful speech that was impassioned but measured in denouncing the Hamas terror attacks and declaring unshakable U.S. support for Israel. Last night, in a rambling address in Florida, Trump praised the skill of Israel’s enemies, criticized Israel’s intelligence and defense capabilities, and complained that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu had tried to claim credit for a U.S. operation that killed a top Iranian general while Trump was president.

At this somber moment, Trump delivered exactly the sort of erratic, self-absorbed performance that his critics have said make him unreliable in a crisis. Trump’s remarks seemed designed to validate what Senator Chris Murphy, a Democrat from Connecticut who chairs the Senate Foreign Relations subcommittee that focuses on the Middle East, had told me in an interview a few hours before the former president’s speech. “This is the most delicate moment in the Middle East in decades,” Murphy said. “The path forward to negotiate this hostage crisis, while also preventing other fronts from opening up against Israel, necessitates A-plus-level diplomacy. And you obviously never saw C-plus-level diplomacy from Trump.”

[Franklin Foer: Biden will be guided by his Zionism]

The crisis is highlighting more than the distance in personal demeanor between the two men. Two lines in Biden’s speech on Tuesday point toward the policy debate that could be ahead in a potential 2024 rematch over how to best promote international stability and advance America’s interests in the world.

Biden emphasized his efforts to coordinate support for Israel from U.S. allies within and beyond the region. And although Biden did not directly urge Israel to exercise “restraint” in its ongoing military operations against Hamas, he did call for caution. Referring to his conversation with Netanyahu, Biden said, “We also discussed how democracies like Israel and the United States are stronger and more secure when we act according to the rule of law.” White House officials acknowledged this as a subtle warning that the U.S. was not giving Israel carte blanche to ignore civilian casualties as it pursues its military objectives in Gaza.

Both of Biden’s comments point to crucial distinctions between his view and Trump’s of the U.S. role in the world. Whereas Trump relentlessly disparaged U.S. alliances, Biden has viewed them as an important mechanism for multiplying America’s influence and impact—by organizing the broad international assistance to Ukraine, for instance. And whereas Trump repeatedly moved to withdraw the U.S. from international institutions and agreements, Biden continues to assert that preserving a rules-based international order will enhance security for America and its allies.

Even more than in 2016, Trump in his 2024 campaign is putting forward a vision of a fortress America. In almost all of his foreign-policy proposals, he promises to reduce American reliance on the outside world. He has promised to make the U.S. energy independent and to “implement a four-year plan to phase out all Chinese imports of essential goods and gain total independence from China.” Like several of his rivals for the 2024 GOP nomination, Trump has threatened to launch military operations against drug cartels in Mexico without approval from the Mexican government. John Bolton, one of Trump’s national security advisers in the White House, has said he believes that the former president would seek to withdraw from NATO in a second term. Walls, literal and metaphorical, remain central to Trump’s vision: He says that, if reelected, he’ll finish his wall across the Southwest border, and last weekend he suggested that the Hamas attack was justification to restore his ban on travel to the U.S. from several Muslim-majority nations.

Biden, by contrast, maintains that America can best protect its interests by building bridges. He’s focused on reviving traditional alliances, including extending them into new priorities such as “friend-shoring.” He has also sought to engage diplomatically even with rival or adversarial regimes, for instance, by attempting to find common ground with China over climate change.

These differences in approach likely will be muted in the early stages of Israel’s conflict with Hamas. Striking at Islamic terrorists is one form of international engagement that still attracts broad support from Republican leaders. And in the Middle East, Biden has not diverged from Trump’s strategy as dramatically as in other parts of the world. After Trump severely limited contact with the Palestinian Authority, Biden has restored some U.S. engagement, but the president hasn’t pushed Israel to engage in full-fledged peace negotiations, as did his two most recent Democratic predecessors, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. Instead, Biden has continued Trump’s efforts to normalize relations between Israel and surrounding Sunni nations around their common interest in countering Shiite Iran. (Hamas’s brutal attack may have been intended partly to derail the ongoing negotiations among the U.S., Israel, and Saudi Arabia that represent the crucial next stage of that project.) Since the attack last weekend, Trump has claimed that Hamas would not have dared to launch the incursion if he were still president, but he has not offered any substantive alternative to Biden’s response.

Yet the difference between how Biden and Trump approach international challenges is likely to resurface before this crisis ends. Even while trying to construct alliances to constrain Iran, Biden has also sought to engage the regime through negotiations on both its nuclear program and the release of American prisoners. Republicans have denounced each of those efforts; Trump and other GOP leaders have argued, without evidence, that Biden’s agreement to allow Iran to access $6 billion in its oil revenue held abroad provided the mullahs with more leeway to fund terrorist groups like Hamas. And although both parties are now stressing Israel’s right to defend itself, if Israel does invade Gaza, Biden will likely eventually pressure Netanyahu to stop the fighting and limit civilian losses well before Trump or any other influential Republican does.

Murphy points toward another distinction: Biden has put more emphasis than Trump on fostering dialogue with a broad range of nations across the region. Trump’s style “was to pick sides, and that meant making enemies and adversaries unnecessarily; that is very different from Biden’s” approach, Murphy told me. “We don’t know whether anyone in the region right now can talk sense into Hamas,” Murphy said, “but this president has been very careful to keep lines of communication open in the region, and that’s because he knows through experience that moments can come, like this, where you need all hands on deck and where you need open lines to all the major players.”

[Read: ‘The Middle East region is quieter today than it has been in two decades’]

In multiple national polls, Republican and Democratic voters now express almost mirror-image views on whether and how the U.S. should interact with the world. For the first time in its annual polling since 1974, the Chicago Council on Global Affairs this year found that a majority of Republicans said the U.S. would be best served “if we stay out of world affairs,” according to upcoming results shared exclusively with The Atlantic. By contrast, seven in 10 Democrats said that the U.S. “should take an active part in world affairs.”

Not only do fewer Republicans than Democrats support an active role for the U.S. in world affairs, but less of the GOP wants the U.S. to compromise with allies when it does engage. In national polling earlier this year by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center, about eight in 10 Democrats said America should take its allies’ interests into account when dealing with major international issues. Again in sharp contrast, nearly three-fifths of GOP partisans said the U.S. instead “should follow its own interests.”

As president, Trump both reflected and reinforced these views among Republican voters. Trump withdrew the U.S. from the World Health Organization, the United Nations Human Rights Council, the Paris climate accord, and the nuclear deal with Iran that Obama negotiated, while also terminating Obama’s Trans-Pacific Partnership trade talks. Biden effectively reversed all of those decisions. He rejoined both the Paris Agreement and the WHO on his first days in office, and he brought the U.S. back into the Human Rights Council later in 2021. Although Biden did not resuscitate the TPP specifically, he has advanced a successor agreement among nations across the region called the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework. Biden has also sought to restart negotiations with Iran over its nuclear program, though with little success.

Peter Feaver, a public-policy and political-science professor at Duke University, told me he believes that Trump wasn’t alone among U.S. presidents in complaining that allies were not fully pulling their weight. What makes Trump unique, Feaver said, is that he didn’t see the other side of the ledger. “Most other presidents recognized, notwithstanding our [frustrations], it is still better to work with allies and that the U.S. capacity to mobilize a stronger, more action-focused coalition of allies than our adversaries could was a central part of our strength,” said Feaver, who served as a special adviser on the National Security Council for George W. Bush. “That’s the thing that Trump never really understood: He got the downsides of allies, but not the upsides. And he did not realize you do not get any benefits from allies if you approach them in the hyper-transactional style that he would do.”

Biden, Feaver believes, was assured an enthusiastic reception from U.S. allies because he followed the belligerent Trump. But Biden’s commitment to restoring alliances, Feaver maintains, has delivered results. “There’s no question in my mind that Biden got better results from the NATO alliance [on Ukraine] in the first six months than the Trump team would have done,” Feaver said.

As the Middle East erupts again, the biggest diplomatic hurdle for Biden won’t be marshaling international support for Israel while it begins military operations; it will be sustaining focus on what happens when they end, James Steinberg, the dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, told me. “The challenge here is how do you both reassure Israel and send an unmistakably tough message to Hamas and Iran without leading to an escalation in this crisis,” said Steinberg, who served as deputy secretary of state for Obama and deputy national security adviser for Clinton. “That’s where the real skill will come: Without undercutting the strong message of deterrence and support for Israel, can they figure out a way to defuse the crisis? Because it could just get worse, and it could widen.”

In a 2024 rematch, the challenge for Biden would be convincing most Americans that his bridges can keep them safer than Trump’s walls. In a recent Gallup Poll, Americans gave Republicans a 22-percentage-point advantage when asked which party could keep the nation safe from “international terrorism and military threats.” Republicans usually lead on that measure, but the current advantage was one of the GOP’s widest since Gallup began asking the question, in 2002.

This new crisis will test Biden on exceedingly arduous terrain. Like Clinton and Obama, Biden has had a contentious relationship with Netanyahu, who has grounded his governing coalition in the far-right extremes of Israeli politics and openly identified over the years with the GOP in American politics. In this uneasy partnership with Netanyahu, Biden must now juggle many goals: supporting the Israeli prime minister, but also potentially restraining him, while avoiding a wider war and preserving his long-term goal of a Saudi-Israeli détente that would reshape the region. It is exactly the sort of complex international puzzle that Biden has promised he can manage better than Trump. This terrible crucible is providing the president with another opportunity to prove it.