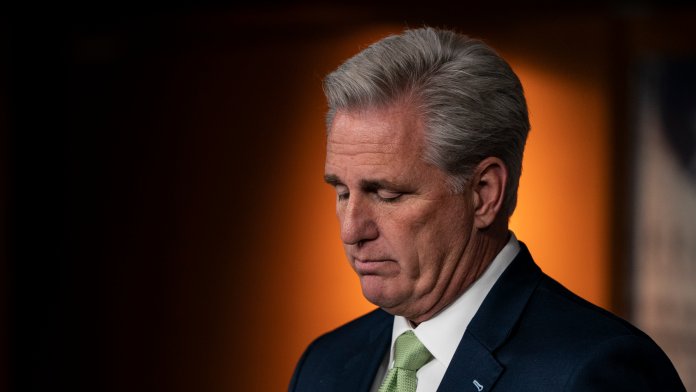

The fall of House Speaker Kevin McCarthy today demonstrated again that the one sin that cannot be forgiven in the modern Republican Party is being seen as failing to fight the Democratic agenda by any means necessary.

Of all the accusations that could be leveled against McCarthy, the notion that he was insufficiently committed to battling Democrats would not seem high on the list. As the GOP minority leader in the previous Congress, McCarthy voted to reject the 2020 election results in two key states and tried to impede the House committee that investigated the January 6 insurrection. Then, as speaker this year, he backed the GOP vote last summer to censure Democratic Representative Adam Schiff over his role in investigating former President Donald Trump while Democrats held the majority; empowered hard-line Republican conservatives to undertake sweeping investigations of President Joe Biden’s administration as well as his son Hunter; and even launched, on his own authority, an impeachment inquiry into the president without any hard evidence of wrongdoing.

[Read: Kevin McCarthy’s brief speakership meets its end]

Yet on two occasions this year, McCarthy refused to risk chaos in the domestic and global economy, choosing instead to accept bipartisan deals with Democrats, first to avoid default on the federal debt and then to keep the federal government open when it faced a possible shutdown last weekend. And that was simply too much collaboration for the eight hard-line conservative Republicans who voted to remove him today, making him the first speaker ever forced out by a motion to vacate the position.

The proximate cause of McCarthy’s fall was his decision, during his agonizing 15-ballot ascent to the speakership in January, to accept a change in House rules that allowed a single member to file a motion to remove him. That let Representative Matt Gaetz trigger the process that doomed McCarthy, even though the majority of the GOP conference voted to maintain him as their leader.

Yet McCarthy’s removal also underscored how the incentives in the modern GOP coalition now almost entirely push in one direction: toward greater conflict with Democrats and the embrace of polarizing policies that reflect the priorities and grievances of the GOP base. It’s no coincidence that critics accused McCarthy of not fighting hard enough for conservative demands at the same moment that Trump and the other 2024 GOP presidential contestants are advancing militant ideas once considered politically radioactive, such as deploying the U.S. military into Mexico to attack drug cartels, ending birthright citizenship for the U.S.-born children of undocumented immigrants, ripping up civil-service protections for government workers, and dispatching the National Guard into blue cities to fight crime.

“Certainly if you step back at 30,000 feet, whatever the particular causes or idiosyncrasies of this decision, it will be part of a general sense of the party going further and further in this hard-line direction,” Bill Kristol, a conservative strategist, told me.

In one respect, McCarthy’s demise continues a cycle among House Republicans that now traces back nearly half a century. From the late 1970s through the ’80s, a coterie of combative young House members led by Newt Gingrich and Vin Weber rose to prominence by founding a group, called the Conservative Opportunity Society, that accused Republican congressional leaders—and, at times, even then-President Ronald Reagan—of negotiating too many deals with Democrats.

Gingrich’s pugnacious rejection of cooperation carried him to the speakership when Republicans recaptured the chamber in 1994, after four decades in the minority. But within a few years, Gingrich faced his own rebellion on the right from critics who thought he was too quick to cooperate with then-President Bill Clinton. Gingrich eventually resigned from the speakership under pressure after the GOP suffered unexpected House losses in the 1998 midterm election, following its move to impeach Clinton over his affair with a White House intern.

The pattern resurfaced after Republicans won a sweeping House majority in 2010. Representative John Boehner, an old-school Republican who ascended to the speakership, faced an unending barrage of criticism from conservatives rooted in the new Tea Party movement over his attempts to reach agreements with Democratic President Barack Obama to avoid a debt default or government shutdown. Boehner resigned from the speakership and Congress itself in 2015, one step ahead of conservative critics in his conference determined to remove him. The same dynamic unfolded under Boehner’s successor as speaker, Representative Paul Ryan, who lasted only two tumultuous terms before deciding to leave Congress and not seek reelection in 2018.

McCarthy found himself caught in the same undertow as Boehner and Ryan, with a portion of his conference immovably convinced that he was conceding too much ground to Democrats. “We saw it with Boehner and saw it with Ryan, and now this is, of course, the epitome of it,” former Democratic Representative David Price, a political scientist who has written several books on Congress, told me.

In the first speech from critics during the debate over McCarthy’s removal, Republican Representative Bob Good of Virginia echoed the arguments that the right had raised against Boehner and Ryan. After arriving in Congress in 2021, Good declared, he was frustrated that Republicans “had not used every tool at our disposal to fight against the harmful, radical Democrat agenda that is destroying the country.” McCarthy had promised something different, Good insisted, but had failed to take the fight to Democrats hard enough. “We need a speaker who will fight for something, anything, other than just staying or becoming speaker,” Good said.

The key difference from those earlier episodes is that the attack on McCarthy came even though he conceded far more to his critics on the right than Boehner or Ryan did. McCarthy’s strategy as speaker generally was to give the right almost everything it demanded and to expect the members from more competitive districts (including the 18 in districts that voted for Biden in 2020 and another 16 in seats that only narrowly preferred Trump) to eventually support him. By and large, they did so. And today, the members from that competitive terrain stood indivisibly beside McCarthy, perhaps fearful that whoever comes next would create even more problems for them. The Republicans from more competitive seats “are very much at risk in 2024, and yet I don’t know what their limits might be,” Price said. “They haven’t revealed that yet. And so all the attention is on the far right.”

[Read: Kevin McCarthy finally defies the right]

As today’s vote demonstrated, most House Republicans were comfortable with McCarthy’s leadership. Yet the fact that a rump group of conservatives still rejected him after all his concessions to the right captures the seemingly boundless sense of urgency and threat that now animates the GOP coalition. For years, Trump and other party leaders have told their voters that the Democratic agenda represents an effort to erase and uproot America as these voters understand it; in his last public rally before the January 6 insurrection, Trump declared that if Democrats won control of the Senate, “America as you know it will be over, and it will never—I believe—be able to come back again.”

As Trump’s commanding lead in the GOP presidential race demonstrates, there’s enormous receptivity in the party for that apocalyptic message. And it’s those fears of being displaced in a changing America that have created the cycle in which the pressure on Republican congressional leaders perpetually pushes them toward harsher tactics and more aggressive policies. Former Republican Representative Tom Davis, who chaired the National Republican Congressional Committee, notes that the hard-liners who deposed McCarthy are accurately reflecting the views of their own voters. “It’s frustration and anger at Washington, and we are going to throw sand in the wheels at whatever they are going to do there,” Davis told me a few hours before McCarthy’s fall. “That’s the level of anger out there in these districts. Blame it on members, but voters elected these folks.”

The January 6 attack on the Capitol provided one grim measure of how that anger bubbling through large swaths of the Republican base can trigger tumultuous and destabilizing events. McCarthy’s removal today showed another. It’s not likely that either was the last.