In 2019, a mnemonic began to circulate on the internet: “If the Naomi be Klein / you’re doing just fine / If the Naomi be Wolf / Oh, buddy. Ooooof.” The rhyme recognized one of the most puzzling intellectual journeys of recent times—Naomi Wolf’s descent into conspiracism—and the collateral damage it was inflicting on the Canadian climate activist and anti-capitalist Naomi Klein.

Until recently, Naomi Wolf was best known for her 1990s feminist blockbuster The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women, which argued that the tyranny of grooming standards—all that plucking and waxing—was a form of backlash against women’s rights. But she is now one of America’s most prolific conspiracy theorists, boasting on her Twitter profile of being “deplatformed 7 times and still right.” She has claimed that vaccines are a “software platform” that can “receive ‘uploads’ ” and is mildly obsessed with the idea that many clouds aren’t real, but are instead evidence of “geoengineered skies.” Although Wolf has largely disappeared from the mainstream media, she is now a favored guest on Steve Bannon’s podcast, War Room.

All of this is particularly bad news for Klein, for the simple reason that people keep mistaking the two women for each other. Back in 2011, when she first noticed the confusion—from inside a bathroom stall, she heard two women complain that “Naomi Klein” didn’t understand the demands of the Occupy movement—this was merely embarrassing. The movement sprang from Klein’s part of the left, and in October of that year she was invited to speak to Occupy New York. Was it their shared first name, their Jewishness, or their brown hair with blond highlights? Even their partners’ names were similar: Avram Lewis and Avram Ludwig. Klein was struck that both had experienced rejection from their peer groups (in her case, by fellow students when she first criticized Israel in the college newspaper).

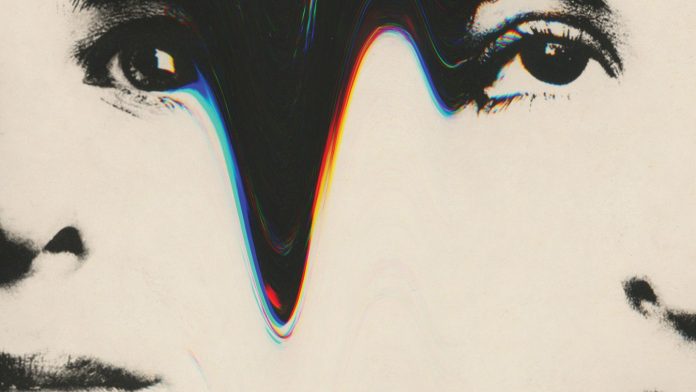

Klein had once admired The Beauty Myth, but she realized to her horror that Wolf had drifted from feminist criticism to broader social polemics. When she picked up Wolf’s 2007 book, The End of America: Letter of Warning to a Young Patriot, her own book, out the same year, came to mind. “I felt like I was reading a parody of The Shock Doctrine, one with all the facts and evidence carefully removed.” To Klein, the situation began to seem sinister, even threatening. She was being eaten alive. “Other Naomi—that is how I refer to her now,” Klein writes at the beginning of her new book, Doppelganger: A Trip Into the Mirror World. “A person whom so many others appear to find indistinguishable from me. A person who does many extreme things that cause strangers to chastise me or thank me or express their pity for me.”

The confusion was particularly galling because No Logo (1999), Klein’s breakout work, was a manifesto against branding. And yet here she was, feeling an urgent need to protect her own personal brand from this interloper. Klein asserts that she didn’t want to write Doppelganger—“not with the literal and metaphorical fires roiling our planet,” she confesses with a hint of pomposity—but found herself ever more obsessed by Wolf’s conspiracist turn. How do you go from liberal darling to War Room regular within a decade?

Like Klein, I loved The Beauty Myth as a young woman, and then largely forgot about Wolf until 2010, when Julian Assange was arrested for alleged sex offenses (the charges were later dropped), and she claimed that Interpol was acting as “the world’s dating police.” Two years later, she published Vagina: A New Biography, which mixed sober accounts of rape as a weapon of war with a quest to cure her midlife sexual dysfunction through “yoni massages” and activating “the Goddess array.” In one truly deranged scene, a friend hosts a party at his loft and serves pasta shaped like vulvae, alongside salmon and sausages. The violent intermingling of genital-coded food overwhelms Wolf, who experiences it as an insult to womanhood in general and her own vagina in particular, and suffers writer’s block for the next six months. (I suspect that the friend was just trying to get into the spirit of Wolf’s writing project.) I remember beginning to wonder around this time whether Wolf might be a natural conspiracy theorist who had merely lucked into writing about one conspiracy—the patriarchy—that happened to be true.

Her final exile from the mainstream can probably be dated to 2019, when she was humiliated in a live radio interview during the rollout of her book Outrages: Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love. She had claimed that gay men in Victorian England were regularly executed for sodomy, but the BBC host Matthew Sweet noted that the phrase death recorded in the archives meant that the sentence had been commuted, rather than carried out. It was a grade A howler, and it marked open season on her for all previous offenses against evidence and logical consistency. The New York Times review of Outrages referred to “Naomi Wolf’s long, ludicrous career.” In the U.K., the publisher promised changes to future editions, and the release of the U.S. edition was canceled outright.

Klein dwells on this incident in Doppelganger, and rightly so: “If you want an origin story, an event when Wolf’s future flip to the pseudo-populist right was locked in, it was probably that moment, live on the BBC, getting caught—and then getting shamed, getting mocked, and getting pulped.” If the intelligentsia wouldn’t lionize Wolf, then the Bannonite right would: She could enter a world where mistakes don’t matter, no one feels shame, and fact-checkers are derided as finger-wagging elitists.

“These people don’t disappear just because we can no longer see them,” Klein reminds any fellow leftists who might be enthusiastic about public humiliation as a weapon against the right. Denied access to the mainstream media, the ostracized will be welcomed on One America News Network and Newsmax, or social-media sites such as Rumble, Gettr, Gab, Truth Social, and Elon Musk’s new all-crazy-all-the-time reincarnation of Twitter as X. On podcasts, the entire heterodox space revels in “just asking questions”—and then not caring about the peer-reviewed answers. By escaping to what Klein calls the “Mirror World,” Wolf might have lost cultural capital, but she has not lost an audience.

[Helen Lewis: Why so many conservatives feel like losers]

Klein notes that this world is particularly hospitable to those who can blend personal and social grievances into an appealing populist message—I am despised by the pointy-heads, just as you are. She ventures “a kind of equation for leftists and liberals crossing over to the authoritarian right that goes something like this: Narcissism (Grandiosity) + Social media addiction + Midlife crisis ÷ Public shaming = Right wing meltdown.” She is inclined to downplay “that bit of math,” though, and feels uncomfortable putting Wolf on the couch. Nonetheless, I’m struck by how narcissism (in the ubiquitous lay sense of the term) is key to understanding conspiracy-theorist influencers and their followers. If you feel disrespected and overlooked in everyday life, then being flattered with the idea that you’re a special person with secret knowledge must be appealing.

Klein’s real interest, as you might expect from her previous work, tends more toward sociology than psychology. Her doppelgänger isn’t an opportunist or a con artist, Klein decides, but a genuine believer—even if those beliefs have the happy side effect of garnering her attention and praise. But what about the culture that has enabled her to thrive?

At first, I thought what I was seeing in my doppelganger’s world was mostly grifting unbound. Over time, though, I started to get the distinct impression that I was also witnessing a new and dangerous political formation find itself in real time: its alliances, worldview, slogans, enemies, code words, and no-go zones—and, most of all, its ground game for taking power.

To explore this ambitious agenda, the book ranges widely and sometimes tangentially. At one point, Klein finds herself listening to hours of War Room, hosted by a man who has built a dark empire of profitable half-truths. Why does Klein find Bannon so compelling? Here Doppelganger takes a startling turn. The answer is that, quite simply, game recognizes game. Klein’s cohort on the left attacks Big Pharma profits, worries about “surveillance capitalism,” and sees Davos and the G7 as a cozy cabal exploiting the poor. Understandably, she hears Other Naomi talk with Bannon about vaccine manufacturers’ profits, rail against Big Tech’s power to control us, and make the case that Klaus Schwab of the World Economic Forum has untold secret power, and she can’t help noting some underlying similarities. When Bannon criticizes MSNBC and CNN for running shows sponsored by Pfizer, telling his audience that this is evidence of rule “by the wealthy, for the wealthy, against you,” Klein writes, “it strikes me that he sounds like Noam Chomsky. Or Chris Smalls, the Amazon Labor Union leader known for his EAT THE RICH jacket. Or, for that matter, me.”

[From the July/August 2022 issue: Steve Bannon, American Rasputin]

This is Doppelganger at its best, acknowledging the traits that make us all susceptible to manipulation. In a 2008 New Yorker profile of Klein, her husband described her as a “pattern recognizer,” adding: “Some people feel that she’s bent examples to fit the thesis. But her great strength is helping people recognize patterns in the world, because that’s the fundamental first step toward changing things.” Of course, overactive pattern recognition is also the essence of conspiracism, and a decade and a half later, Klein expresses more caution about her superpower. When 9/11 truthers turn up at her events—drawn perhaps by her criticism in The Shock Doctrine of George W. Bush’s response to the tragedy—their presence leads her to conclude “that the line between unsupported conspiracy claims and reliable investigative research is neither as firm nor as stable as many of us would like to believe.”

We live in a world where the U.S. government has done outlandish stuff: The Tuskegee experiment, MK-Ultra, Iran-Contra, and Watergate are all conspiracies that diligent journalism proved to be true. QAnon’s visions of Hollywood child-sex rings might be a mirage, but the Catholic Church’s abuse of children in Boston was all too real—and uncovering it won The Boston Globe a Pulitzer Prize. Klein worries about whether a political movement can generate mass appeal without resorting to populism, and about how to stop her criticisms of elite power from being co-opted by her opponents and distorted into attacks on the marginalized.

[Read: A 2014 interview with Naomi Klein about climate politics ]

However, Klein’s (correct) diagnosis of American conspiracism as a primarily right-wing pathology prevents her from fully acknowledging the degree to which it has sometimes infected her own allies and idols. In Doppelganger, Klein notes that anti-Semitism has served as “the socialism of fools”—stirred up to deflect popular anger away from the elite—but she does not discuss the anti-Jewish bigotry in the British Labour Party under its former leader Jeremy Corbyn, whom she endorsed in the 2019 election. (Corbyn once praised a mural of hook-nosed bankers counting money on a table held up by Black people, and his supporters suggested that his critics were Israeli stooges.) The party has since apologized for not taking anti-Semitism seriously enough.

At times, this can be a frustrating book. Near the end, Klein says she requested an interview with Wolf, promising that it would be “a respectful debate” about their political disagreements. She also hoped to remind Wolf of their original meeting, more than three decades earlier—when Wolf, then 28, captivated the 20-year-old Klein, showing her the possibilities of what a female author could be. But Wolf never responded to the request, and the doppelgängers have not met face-to-face since then.

Still, Klein emerges with a sense of resolution. She writes that the confusion between the two of them has lately died down, now that Other Naomi has become an “unmistakable phenomenon unto herself.” Even better, the situation has introduced “a hefty dose of ridiculousness into the seriousness with which I once took my public persona.” Not that the zealous Klein has disappeared: The next few pages are a paean to collective organizing, worker solidarity, and “cities in the grips of revolutionary fervor.”

Doppelganger is least interesting when Klein returns to her comfort zone, but her brutally honest forays into self-examination are fascinating. The book is also a welcome antidote to the canceling reflex of our moment and a bracing venture across ideological lines. Klein successfully makes the case that the American left is more tethered to reality than the right—not because it is composed of smarter or better people, but because it has not lost touch with the mechanisms, such as scientific peer review and media pluralism, that act as a check on our worst instincts. Exposed to many of the same forces as her conspiracist doppelgänger—fame, cancellation, trauma, COVID isolation—this Naomi stayed fine. That has to offer us some hope.

This article appears in the October 2023 print edition with the headline “The Other Naomi.”