This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

He shuffled quietly into the courtroom and took his seat at the defense table. He looked strangely small sitting there flanked by lawyers—his shoulders slumped, his hands in his lap, his 6-foot-3-inch frame seeming to retreat into itself. When he spoke—“Not guilty”—it came out hoarse, almost a whisper. Pundits and reporters had spent weeks trying to imagine what this moment would look like. How would a former president—especially one who prided himself on showmanship—behave while under arrest? Would he act smug? Defiant? Righteously indignant?

No one predicted that he would look quite so humiliated.

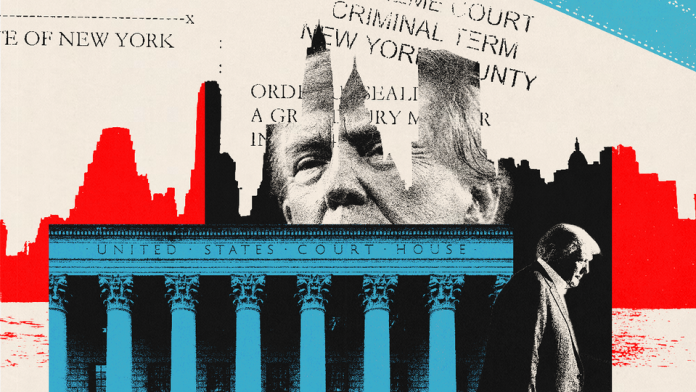

Of course, becoming the first ex-president in American history to be charged with a crime is not exactly a coveted résumé line. But Donald Trump’s indictment yesterday marked a low point in another way too: For a man who’s long harbored a distinctive form of class anxiety rooted in his native New York, Trump’s arraignment in Manhattan represented the ultimate comeuppance.

The island of Manhattan plays an important role in the Donald Trump creation myth. In speeches and interviews over the years, Trump has repeatedly recalled peering across the East River as a young man, yearning to expand the family real-estate business and compete with the city’s biggest developers. For a kid born in Queens—even one who grew up in a rich family—Manhattan seemed like the center of the universe.

[Read: The outer-borough president]

“I started off in a small office with my father in Brooklyn and Queens,” Trump said in the 2015 speech launching his campaign. “And my father said … ‘Donald, don’t go into Manhattan. That’s the big leagues. We don’t know anything about that. Don’t do it.’ I said, ‘I gotta go into Manhattan. I gotta build those big buildings. I gotta do it, Dad. I’ve gotta do it.’”

In the version of the story Trump likes to tell, he went on to cross the river, conquer the island, and cement his victory by erecting an eponymous skyscraper in the middle of town. His childhood dream came true.

But Trump was never really accepted by Manhattan’s old-money aristocracy. To the city’s elites, he was just another nouveau riche wannabe with bad manners and a distasteful penchant for self-promotion. They recognized the type—the outer-borough kid who’d made good—and they made sure he knew he wasn’t one of them. With each guest list that omitted his name, with each VIP invitation that didn’t come, Trump’s resentment burned hotter—and his desire for revenge deepened.

Today, the old hierarchies that defined the New York of Trump’s youth are largely gone, replaced by new ones. (Brooklyn, the middle-class backwater where Trump’s father kept his office, is now home to enough pretentious white people that even the snootiest Manhattanites have to acknowledge the borough.) Trump, meanwhile, isn’t even a New Yorker anymore, having changed his voter registration to Florida in 2019 and retreated to the more hospitable confines of Mar-a-Lago after leaving the White House.

But Trump never forgot the island that rejected him. And this week, he was forced to return to it—not in triumph, but in disgrace. Hundreds of journalists descended on Lower Manhattan to chronicle each indignity: the courthouse door gently shutting on him because nobody bothered to hold it open, the judge sternly instructing him to rein in his social-media rhetoric about the case. At one point, shortly after Trump entered the courtroom, someone in the overflow room, where reporters and others were watching a closed-circuit feed, began to whistle “Hail to the Chief,” drawing stifled laughter.

[John Hendrickson: Inside Manhattan Criminal Court with Donald Trump]

In the past, Trump has succeeded in using his humiliations to his benefit. It’s a big part of why he excels at playing a populist on the campaign trail. When Trump railed against the corrupt ruling class in 2016, he wasn’t just channeling the anger of his supporters; he was expressing something he felt viscerally. Yes, his personal grievances with the “elites”—the ego-wounding snubs—might have been petty, but the anger was real. And for many of his followers, that was enough.

Now he’s trying to pull off that trick again. In the weeks leading up to his indictment, Trump has sought to cast Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg’s investigation as an act of political persecution—aimed not just at him, but at the entire MAGA movement. “WE MUST SAVE AMERICA!” he shout-posted on Truth Social last month. “PROTEST, PROTEST, PROTEST!”

A modest contingent of pro-Trump demonstrators gathered in a park across the street from the courthouse yesterday, separated by police barricade from a larger group of counterprotesters. But the relatively muted MAGA presence, compared with the crowds of onlookers relishing the moment, only underscored how alienated the former president has become from the city with which he was once synonymous. The scene was heavier on performance artists and grifters than outraged true believers. A woman in a QAnon T-shirt strutted and gyrated for reporters as she rambled about Satan and the financial system, periodically punctuating her comments with “Bada bing!” A Trump supporter burned sage to ward off evil spirits, prompting one bystander to ask, “Is someone cooking soup?” The Naked Cowboy made an appearance.

A handful of Trump’s New York–based supporters tried to convince me that this was still his town. Dion Cini—a MAGA-merch salesman who drew attention for his giant TRUMP OR DEATH flag and his liberal deployment of flagpole-based innuendos—told me he lived in Brooklyn. “Trump country!” he declared.

I asked Cini if he really believed that New York could still be considered Trump country. Cini responded by launching into an enthusiastic (and exaggerated) recitation of how much of the city had been built by the Trumps. “Sheepshead Bay was built by Trump. All 50,000 homes,” Cini said, claiming that he lives in a Trump-built house there himself. “How many towers were built by Trump? The Javits Center! I mean, you name it—the Wollman Rink, the carousel in Central Park. And they call him a Nazi. I mean, did Hitler ever build a carousel?”

After Cini wandered away, another Trump supporter named Scott Schultz approached me. Schultz said he also lives in Brooklyn’s Sheepshead Bay neighborhood, but he disagreed that it was “Trump country.” He can’t even put a Trump sign outside his house, because he knows it will be immediately defaced, Schultz said. He fantasized about a day when New Yorkers could celebrate Trump simply as a product of their city.

“Most other [places], when someone becomes president, they have pride in that,” Schultz told me. “There was no pride at all … They want to wipe him clean. They rejected him.”

Trump didn’t linger in the city after his arraignment. There was no impromptu press conference on the courthouse steps or chest-thumping speech to his supporters outside. Instead, his motorcade whisked him away to LaGuardia Airport for a flight back to Florida. He’d been in New York barely 24 hours. For now, at least, he seems intent on waging his battle with the Manhattan haters from a distance. Writing on Truth Social yesterday, Trump proposed moving his trial to Staten Island.