Photographs by Adam Riding

Twilight offered welcome concealment when we met at the prearranged hour. “I really haven’t gone out anywhere” since well before the election, Bill Gates, the outgoing Republican chair of the Maricopa County board of supervisors, told me in mid-November. He’d agreed to meet for dinner at an outdoor restaurant in the affluent suburb of Scottsdale, Arizona, but when he arrived, he kept his head down and looked around furtively. “Pretty much every night, I just go home, you know, with my wife, and maybe we pick up food, but I’m purposely not going out right now. I don’t necessarily want to be recognized.” He made a point of asking me not to describe his house or his car. Did he carry a gun, or keep one at home? Gates started to answer, then stopped. “I’m not sure if I want that out there,” he said.

As a younger politician, not so long ago, Gates had been pleased and flattered to be spotted in public. Now 51 years old, he never set out to become a combatant in the democracy wars. He shied away from the role when it was first thrust upon him, after the 2020 election, recognizing a threat to his rising career in the GOP. But the fight came to him, like it or not, because the Maricopa County board of supervisors is the election-certification authority for well over half the votes in the state.

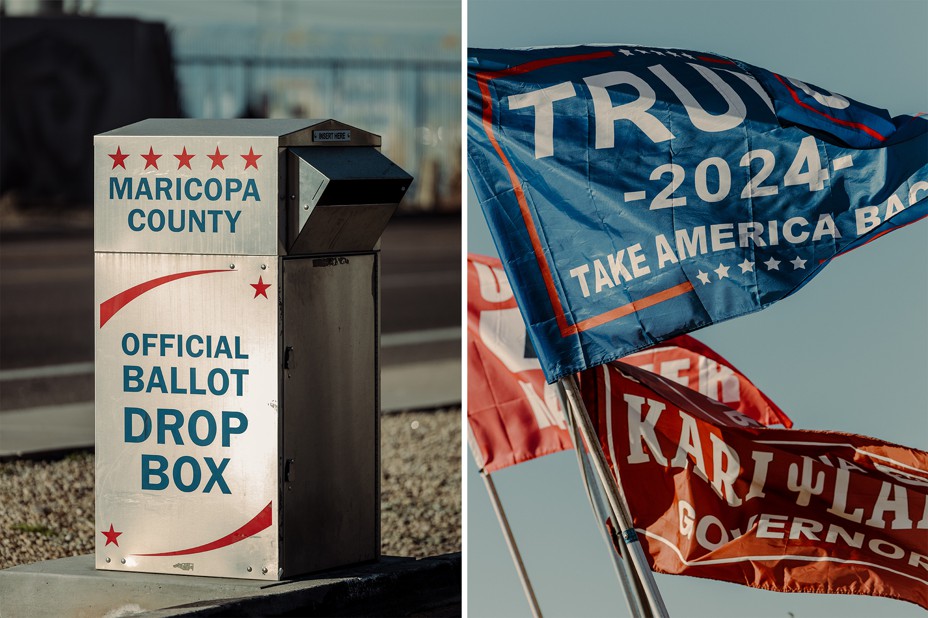

When we spoke, Kari Lake was still contesting her loss in Arizona’s gubernatorial election. Months later, she is still anointing herself “the real governor” and saying that election officials who certified her defeat are “crooks” who “need to be locked up.” She reserves special venom for Gates. Speaking to thousands of raucous supporters in Phoenix on December 18, beneath clouds of confetti, Lake denounced “sham elections … run by fraudsters” and singled him out as the figurehead of a corrupt “house of cards.”

“They are daring us to do something about it,” she said. “We’re going to burn it to the ground.” Then she lowered her mic and appeared to mouth, with exaggerated enunciation, “Burn the fucker to the ground.” To uproarious applause, she went on to invoke the Second Amendment and the bloody American Revolution against a tyrant. “I think we’re right there right now, aren’t we?” she said.

All of that may seem a little beside the point from afar, an inconsequential footnote to a 2022 election season that, mercifully, felt more normal than the last one. But Lake shares Donald Trump’s dark gift for channeling the rage of her supporters toward violence that is never quite spoken aloud.

[From the January 2021 issue: Barton Gellman on Trump’s next insurrection]

In part as a result of her vilification campaign, Gates is stalked on social media, in his inbox and on voicemail, and in public meetings of the board of supervisors. Based on what law enforcement regarded as a credible death threat, Maricopa County Sheriff Paul Penzone removed Gates and his wife from their home in Phoenix on Election Night and dispatched them to a secure location under guard. They knew the drill. “I’ve done it so many times,” Gates recalled. “It’s like, ‘Here we go again.’”

In two successive elections, 2020 and 2022, Gates has had to choose: back his party, or uphold the law. Today, he is a leading defender—in news conferences, in court, and in election oversight—of Arizona’s democratic institutions.

I’d come to Phoenix to try to understand this moment in American politics. November’s midterm election was the first in the country’s history to feature hundreds of candidates running explicitly as election rejectionists. Enough of them were defeated to mark a salutary trend: Swing voters did not seem to favor blatant, self-serving lies about election fraud. That was an encouraging result for democracy, and a balm to many Americans eager for a return to something like political normalcy.

But it was not the whole story. Election deniers won races for secretary of state—the post that oversees election administration—in Alabama, Indiana, South Dakota, and Wyoming. They make up most of the Republican freshman class in Congress. Even some of the losers came very close. Lake’s election-denying ticket mate, Abe Hamadeh, lost the Arizona attorney general’s race by 280 votes.

Of greatest interest to me was the extent to which the narrow losses of MAGA conspiracists gained legitimacy from the words and actions of people like Gates—otherwise low-profile electoral officials, many of them Republican. I wanted to know how he saw the recent election, and what he expected of the next one. The more time I spent with him, and in Arizona, the more uncertain the reprieve of last November appeared.

“I’m politically dead,” Gates told me. It’s what he thinks most of the time, though not always. He toys with thoughts of running again, even running for higher office, but calculates that he has next to no chance of securing his party’s nomination for any office in 2024. If Trump or a successor tries to overturn the vote in January 2025, somebody else will have to be found to push back.

In Maricopa County alone, four of the five supervisors, all of whom have stood shoulder to shoulder in defense of the county’s election machinery, are Republicans. As ultra-MAGA conspiracists continue to dominate the GOP base, what kind of Republicans will be around to safeguard the next election, or the one after that?

Something goes wrong in just about every voting cycle, and even when things go right, there are always details that can be made to look suspicious by fabulists intent on breaking public confidence. Sound elections rely on the competence, the fairness, the transparency, and, in recent years, the courage of election workers.

On Election Day 2022, Gates and other county authorities planned to ward off conspiracy theories with a smooth and efficiently functioning vote. The technology gods had other plans.

The first sign of trouble turned up around 6:30 a.m. One polling center reported what looked like a tabulator malfunction. Ballots were printing on demand, and voters were filling them, but the tabulator spat them out unread. The troubleshooting hotline logged a second call a few minutes later, then a third. Soon, dozens of polling places had tabulation failures. Trouble spots filled the status board at the Maricopa County Tabulation and Election Center, which stood behind a newly built security fence to keep protesters outside.

“And then it’s like, ‘Oh, crap,’” Gates recalled. “This is a widespread issue.” And “we have literally the eyes of the world on this election.” Voter lines backed up and tempers flared. Nobody knew what was wrong. Gates got on the phone with the president of Dominion Voting Systems, which made the tabulators.

Lake and the far-right information ecosystem had promoted the lie that the ballot was rigged long before Election Day. Social media now lit up with claims that election officials had sabotaged their own machines to suppress the vote in Republican neighborhoods. Lake went on television to say, falsely, that her voters were being turned away.

Gates and Stephen Richer, the county recorder, rushed out a video message at 8:52 a.m. Standing in front of a tabulator, Gates said, “We’re trying to fix this problem as quickly as possible, and we also have a redundancy in place. If you can’t put the ballot in the tabulator, then you can simply place it here where you see the number three. This is a secure box where those ballots will be kept for later this evening, where we’ll bring them in here to Central Count to tabulate them.”

It was the sort of rapid public response—factual, practical, and reassuring—that’s become essential since Trump first began poisoning voter confidence with false claims of fraud. But the Lake campaign and its allies nonetheless saw an opportunity to sow doubt and confusion.

“No. DO NOT PUT YOUR BALLOT IN BOX 3 TO BE ‘TABULATED DOWNTOWN,’” Charlie Kirk of Turning Point USA tweeted repeatedly to nearly 2 million followers. Kelli Ward, the Arizona Republican Party chair, posted the same urgent, all-caps advice, adding falsely that “Maricopa County is not turning on their tabulators downtown today!”

Many Lake supporters refused to use the Box 3 option, fearful that their votes would not be counted, and Gates ordered that voters be allowed to try the tabulators as many times as they wanted. The chaos at some polling stations worsened.

The technical error, diagnosed by midmorning, turned out to be that the printers in 43 of the 223 polling places were printing ballots with ink too faint for the tabulators to read. Nobody knew why; the same settings and equipment had worked fine in the August primaries. By early afternoon, technicians had solved the problem by increasing the heat setting on the print fuser.

Lake spread conspiracy theories throughout the day and in the days that followed, as the vote count went on. All Gates and Richer could do was stand in front of cameras, over and over again, answering every question. Box 3, by one or another name, was a standard voting option, employed in most Arizona counties for decades. There were plenty of polling places with short lines. Fewer than 1 percent of ballots were affected by printer issues, and all of them were being counted anyway. A live public video feed showed the tabulation operations, 24 hours a day. No voter had been turned away because of the glitch.

The office of Mark Brnovich, Arizona’s Republican attorney general, amplified Lake’s accusations and warned in a letter against certifying the election results without addressing numerous “concerns regarding Maricopa’s lawful compliance with Arizona election law.” Gates’s lawyer responded that the attorney general’s office had its facts wrong. Gates and his fellow supervisors certified the canvass on November 28. Katie Hobbs, the Democrat, had beaten Lake by 17,117 votes.

Lake filed a lawsuit on December 9, a 70-page complaint filled with florid accusations: sabotaged printers and tabulators, “hundreds of thousands of illegal ballots,” thousands of Republican voters who’d been disenfranchised—all in Maricopa County alone. The judge threw out most of her charges in pretrial rulings. At trial, Lake was unable to supply any persuasive evidence of wrongdoing or identify even one disenfranchised voter or illegal ballot. She lost again in the Court of Appeals on February 16, and now vows to go to the state supreme court. She has raised more than $2.6 million since Election Day, spoke at the Conservative Political Action Conference in Washington, D.C., this past weekend, and seems likely to run for the U.S. Senate next year.

M

ost of the election deniers who lost their races around the country in November conceded defeat, with varying degrees of grace. Pretending to win elections they lost turned out to be harder than Trump made it look. Not many politicians have the former president’s bottomless capacity to live and breathe an alternate reality—or make millions of people care. A pair of Joe Biden speeches on democracy, together with the public hearings of the January 6 committee, had also helped discredit election-fraud charges among independent voters. And right-wing media may have been more cautious about baseless fraud claims after the defamation lawsuits brought against them following their performance in 2020. Lake, a charismatic presence who had honed her television skills as a local news anchor, was one of the few candidates who doubled down on conspiracy talk.

[Read: Trumpism has found its leading lady]

But the impact of Lake’s performance was not hard to see. More than 1.2 million people voted for Lake in the governor’s race, three-quarters of a million of them in Maricopa. Many, swept up in her reality-distortion field, believed sincerely that the election had been stolen. Scores of them surged into the board of supervisors’ hearing room on November 16, eight days after the election. Gates had scheduled public comments on election procedures. He sat on the dais with the demeanor of a nervous high-school principal, determined to keep rowdy students under control.

“I’m just going to say this right now: We have children watching this,” he told the crowd, improbably. “So please, no profanity.”

Everyone who signed up to speak would have two minutes. No interruptions. “We’re not going to have any outbursts, okay?” he said. The audience laughed, mocking him.

A woman named Raquel stood up.

“Mr. Chairman Bill Gates and Recorder Richer, you both have lost all credibility and any shred of integrity—”

Applause interrupted her. Gates narrowed his eyes.

Raquel accused Gates of founding “a political-action committee to specifically defeat MAGA candidates” and asked how he could fairly run an election. In 2021, amid a spurious “forensic audit” that tried to prove that Trump had won Arizona the previous year, Gates had made a $500 contribution to a PAC formed by Richer, the county recorder, called Pro-Democracy Republicans of Arizona—“The Arizona election wasn’t stolen” was the first line on its website—but he’d had no role in distributing its funds.

Another woman, Kimberly, told the supervisors that she knew they had sabotaged the ballot printers. “As a former programmer myself, I can tell you there’s no such thing as a glitch,” she said. The crowd, stirring, murmured its assent.

Jeff Zink, a MAGA Republican who had just lost his race for U.S. Congress, brought a more direct sense of grievance. The only reason he had not won, he said, was that “an algorithm took place which shows that at no time did I ever gain any ground whatsoever.” He did not explain what he thought an algorithm is. It did not matter: He had the room behind him.

Some witnesses made specific allegations. Many simply flung vitriol. “I’m just disgusted by your behavior,” said Sheila, a retired city worker. “Look at all these people out here who are suffering so badly because of your falsehoods.”

“You are the cancer that is tearing this nation apart,” said Matt, another speaker, to louder and angrier applause.

“Thank you,” Gates replied tightly.

Several speakers invoked higher powers and threatened divine retribution—or, anyway, retribution in God’s name. “Beware, your sins will find you out,” one speaker said in a quavering voice. Another, a hulk of a man named Michael, said that “God knows what you’ve done … I warn you and I caution you, we got a big God in Jesus’s name.”

Another burst of applause amid angry buzzing. Audience members were beginning to rise from their seats. Two sheriff’s deputies made as if to move toward them and then thought better of it. My sense, sitting near the front, was that the gathering was just below full boil. If the crowd got any hotter, two deputies would not be enough.

“You need to resign today. And I pray that God is going to convict your heart and for what you’ve done,” yelled a furious Lake supporter named Lisette.

Gates tried to respond, beginning to speak of the electoral redundancies that ensure that every vote is counted. But the crowd was standing and shouting. He adjourned the meeting and slipped out a side door, stage right. I joined him a few minutes later in his office across the street. I told Gates that it had looked to me as though the crowd had been making up its mind about whether to rush the dais.

“This is not a game,” he said. “This is very serious. And the danger of violence is just right under the surface.”

Gates picked without enthusiasm at a container of plain chicken and steamed carrots that his wife, the county’s associate presiding judge, had cooked for his lunch. “We’re doing this diet right now,” he said, a bit mournfully. “We’re trying to be good.”

He had rejected the option of packing the room with security, he said. “These are challenging times, because you also don’t want to create a police state, you know? And that’s something that we’re balancing.”

Gates has learned to live with a constant stream of abuse. It began long before the 2022 midterms and has not let up since those elections concluded. One persistent correspondent has written to him several times a month since early 2021. One day, he writes, “Hey I hear little bitch Bill Gates is in hiding? Why? Cause you worked extra hard to steal tao elections … or more? Keep hiding rat shit.” Four days later: “You are scum and deserve to be tried for treason.”

A voicemail left for his chief of staff, Zach Schira, twisted with rage: “I really believe that what we used to do to traitors is what we should do today. Give ’em a fucking Alabama necktie, you piece of shit. Fucking traitor, just like your fucking boss, rigging the election for a little bit of dough, you know? Piece of shit.” (The good old boy who left the message was probably aiming for a lynching metaphor, but he had hit on something else.)

In December, Gates woke up one morning and was moved to post on Twitter about the beauty around him: “If you are in @maricopacounty, step outside and look at the sunrise. We are blessed to live here.” The responses, dozens of them, were almost comically savage.

“Hopefully soon you won’t be able to see that beautiful sunrise, bc you’ll be locked up!”

“Treeeeaaasooon.”

“Quick question. Do you happen to know the penalty for treason? Just curious is all.”

There was more, calling him subhuman, soulless, satanic.

Every now and then, something sufficiently threatening crosses Sheriff Penzone’s desk, and he notifies Gates that it is time to sleep somewhere else. On other occasions, the sheriff will post a pair of undercover deputies outside his home. Most of the time, though, Gates walks and drives and puts himself out there in the world all alone.

Gates knows he is far from the only election official under threat. On January 16, police in Albuquerque, New Mexico, arrested a failed Republican political candidate who’d rejected his defeat and allegedly paid gunmen to shoot at the homes of four Democratic officeholders. On January 26, over in Arizona’s Cochise County, the elections director resigned her post after years of abuse, citing an “outrageous and physically and emotionally threatening” working environment.

According to a fall 2022 survey by the nonpartisan Democracy Fund, one in four election officials have experienced threats of violence because of their work. In the largest jurisdictions, that number increases to two out of three.

[From the April 2023 issue: Adrienne LaFrance on America’s new anarchy]

Gates stays in touch with peers around the country, mostly Republicans, who have stood up against election denial and faced the consequences. They form a little community, like an internet support group, dishing out comfort on bad days and dispatching a friendly word when they see one another in the news.

One member of this informal group is Al Schmidt, who was the sole Republican on the Philadelphia board of elections in the 2020 election and received a deluge of death threats after Trump accused him of being party to corruption. Gates also corresponds with Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and his chief operating officer, Gabriel Sterling, both of whom pushed back against Trump’s demands to “find” enough votes to upend Biden’s victory in that state.

“We have done Zoom meetings,” he told me. “We have met in person. We talk on the phone. We text one another. And it’s very helpful because … if you haven’t gone through this, you don’t really understand. And if you have gone through it, you do.”

The simple banter reminds Gates that he has allies, even if far away.

“Yesterday, Trump endorsed an all-in stop the steal candidate for AG so look for me in handcuffs in early 2023. 😊,” Gates said in a text last June to Maggie Toulouse Oliver, the secretary of state of neighboring New Mexico. He was only half-joking: Abe Hamadeh, who nearly went on to win the attorney general’s race, was vowing to prosecute election officials whom he accused of fraud.

“Omg. Well I’ll come bail you out!! ❤️,” Oliver replied.

Chair of the board of supervisors is not even a full-time job in Maricopa, the fourth-largest county in America, with a population of 4.5 million and a $4.5 billion budget. Gates’s day job is general counsel for Ping, a large Phoenix-based manufacturer of golf clubs and bags. His position is not undemanding, but election controversies sometimes keep him away from the office for days or weeks at a time. His bosses, he said, “have been very understanding.”

It is hard to convey how little his world resembles the one Gates signed up for when he first ran for county supervisor. He grew up as a self-described “political dork” in Phoenix and chose Drake University, in Des Moines, for college because of its champion mock-trial team and because he wanted to see the Iowa caucuses in person. Jack Kemp, Ronald Reagan, and George H. W. Bush were his political heroes.

In 2009, Gates won an appointment to the Phoenix city council, where he developed a reputation as an urban technocrat. When he ran for county supervisor in 2016, the planks of his platform involved vacant strip malls, water and sewer problems, and garbage pickup. He called himself an “economic-development Republican” who “wants government to get out of the way to allow … free enterprise to flourish.”

Gates did not much like Trump in the 2016 campaign, and voted for John Kasich in the primary. When Trump came to town for a rally, Gates told The Arizona Republic that Trump’s views “do not reflect the majority of Arizonans and the majority of Arizona Republicans.”

Even so, like a lot of reluctant Republicans, Gates voted for Trump over Hillary Clinton that year. “I believed he would nominate judges to the federal bench who would exercise judicial restraint, and that Mike Pence would have a calming influence,” he told me. Now that he represents the election-certification authority, Gates will not say how he voted in 2020.

If 2022 was hard on Gates and his colleagues, 2020 was worse—a fact that can reasonably support either optimism or pessimism for 2024. The presidency was at stake, not the governor’s office, and the aftermath of the election fell upon Gates and his fellow supervisors like a toxic spill. Arizona, and Maricopa County in particular, became a major focus of Trump’s cries of fraud. Angry mobs descended on the election command center and the homes of some of the supervisors, shouting “Stop the steal.” Alex Jones of Infowars and Representative Paul Gosar worked up the crowds. Gates called the scene outside the command center “Lollapalooza for the alt right.” Police put up temporary fencing to protect the ongoing tabulation. Inside, the staff could hear chanting and the reverberation of drums.

The incumbent president, wielding all the authority of his position, mobilized not only the MAGA grassroots but also the GOP establishment in service of his pressure campaign. Trump twice tried to get one of Gates’s colleagues, then-chair Clint Hickman, on the phone. Ward, the state Republican chair, began calling and texting Gates relentlessly as the deadline neared to certify the presidential vote, on November 20. “Here’s Sidney Powell’s phone number,” she said, according to Gates, referring to a Trump lawyer who would become notorious for outlandish claims. “Will you please call her?”

“I’m going, ‘Who’s Sidney Powell?’” Gates told me. “I never returned that call.”

In her text messages, which Gates provided to me, Ward recited multiple alleged anomalies and conspiracy theories. She attributed a baseless allegation about the corrupt design of Dominion software to an unnamed “team of fraud investigators.” She worried that “fellow Repubs are throwing in the towel. Very sad. And unAmerican.” She noted, “You all have the power that none of the rest of us have.”

The texts went on and on, alternately lawyerly, angry, and pleading.

Gates replied in the end with four words: “Thanks for your input.”

Had he felt threatened by all the arm-twisting from the state party chair? I asked.

“Threat is a strong word,” he told me, adding, “I felt pressure. I felt like if I didn’t do what she wanted to do, that there would be political ramifications, certainly.”

Gates grew up in local government and had a politician’s instinct not to make enemies. But if he fulfilled his lawful duty, he would become a pariah in the state GOP and an enemy of the president of the United States. Knowing that—and Ward made sure he knew—was supposed to crush all thoughts of resistance.

“Once you make that vote to certify, you know you’re not coming back from that,” Gates said. “People thought because I was nice over all these years that I was weak.”

Gates and his fellow supervisors voted unanimously, on schedule, to certify the 2020 election. But that didn’t slow the campaign to overturn the results. “Stop the steal” sentiment intensified as the year drew to a close. The Republican-dominated state Senate issued a subpoena for all of the county’s paper ballots and voting machines, planning to hand them over to a MAGA-run outfit called Cyber Ninjas to “audit” the results. Gates and his colleagues refused to comply, believing that would be illegal. They filed a lawsuit to void the subpoena.

Gates was doing last-minute shopping at Walgreens at about 5 p.m. on Christmas Eve when Rudy Giuliani called him. He did not recognize the number and ignored it, but he kept the voicemail, which he played for me.

“I have a few things I’d like to talk over with you,” Giulani says, after introducing himself. “Maybe we can get this thing fixed up. You know, I really think it’s a shame that Republicans, sort of, we’re both in this kind of situation. And I think there may be a nice way to resolve it for everybody. So give me a call, Bill. I’m on this number, any time, doesn’t matter, okay? Take care. Bye.”

Gates shook his head at the memory.

“Someone who on 9/11 I had great respect for,” he said. “I didn’t return his call.”

In early 2021, state legislators moved to have Gates and his colleagues taken into custody for contempt if they did not hand over the ballots, notwithstanding the pending court case. Gates assured his crying daughters—there are three of them, now all in college—that he would be all right.

“So I actually shot a video on my camera—this was sort of like, you know, a hostage video,” Gates said. “Like, ‘If, you know, if you’re watching this, I’m now in custody,’ kind of explaining why I had done what I did, why I thought we were right.”

For all the sense of menace, there was something liberating about this period, Gates told me, and it was around this time that he began to speak out more often and more forcefully in defense of elections and the people who run them.

“They made allegations that our employees had deleted files, basically committed crimes,” Gates said. “That’s when this board, along with Recorder Richer and other countywide electeds, stood up and said, ‘We’re going to push back now. This is a lie. You’re accusing our folks of committing crimes. We can’t stand by silent.’”

The county court eventually ruled that Maricopa had to turn over the ballots and voting machines, and the Cyber Ninja circus began. It found no evidence of fraud but stretched on for months, keeping Gates in the news as a foil.

His career, he believed then, was finished. He had no reason to hold back.

“Once you’re dead, there’s nothing they can do to you,” he said. “Right?”

“You know,” Gates told me, “I think this is the most dangerous time for the state of our democracy other than the Civil War.”

By any accounting, the 2020 election was more dangerous than the one last year. Gates knows as well as anyone that it’s too soon to say the worst is behind us. As a presidential nominee, Trump or another candidate could bring a subversive focus and intensity to the party that’s all but impossible during the midterms. More than a third of Republicans are still hard-core Trump supporters, and nearly two-thirds still believe the 2020 election was rigged. The race late last month for chair of the Republican National Committee pitted an incumbent who was all in for Trump against two challengers who competed to be more so.

Yet for all that, and despite what he’s just been through (again), Gates does see hopeful possibilities—possibilities he didn’t see two years ago. Many of the most strident election deniers did lose, he points out. Gripped by MAGA fever, the GOP has now experienced three successive setbacks at the ballot box, in 2018, 2020, and 2022. Some of the party’s elected leaders have distanced themselves from Trump since the midterms, and polls of GOP voters show some softening of support.

If Arizona rejected the extremists who ran for statewide office—Lake and Hamadeh and Mark Finchem, who ran for secretary of state—does that mean a politician like Gates might still have a chance? It’s an important question, because extremists who win primaries won’t always lose local general elections, and in the worst case, it wouldn’t take many extremists in roles like his to throw the country into chaos.

There is no clear answer yet, for Gates or for American democracy. In the biggest picture, the range of plausible outcomes in 2024 is as wide as it has been in living memory.

On January 11, Gates handed over the chair’s gavel to his colleague Clint Hickman. Until next year, when his term expires, Gates will simply be one of five members of the county board.

Recently, he has allowed himself to imagine running for statewide office. Democrats defeated all of the Arizona election deniers in 2022, but perhaps a mainstream Republican could win next time.

“Maybe we can take another shot at this. Maybe we can fight to get candidates who can appeal to the big tent,” he said. “That was the party that I joined.”

Did he really think it could happen as soon as 2024? I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said. “Things change. Two years is a long time in politics.”