The Sierra Club’s Equity Language Guide discourages using the words stand, Americans, blind, and crazy. The first two fail at inclusion, because not everyone can stand and not everyone living in this country is a citizen. The third and fourth, even as figures of speech (“Legislators are blind to climate change”), are insulting to the disabled. The guide also rejects the disabled in favor of people living with disabilities, for the same reason that enslaved person has generally replaced slave : to affirm, by the tenets of what’s called “people-first language,” that “everyone is first and foremost a person, not their disability or other identity.”

The guide’s purpose is not just to make sure that the Sierra Club avoids obviously derogatory terms, such as welfare queen. It seeks to cleanse language of any trace of privilege, hierarchy, bias, or exclusion. In its zeal, the Sierra Club has clear-cut a whole national park of words. Urban, vibrant, hardworking, and brown bag all crash to earth for subtle racism. Y’all supplants the patriarchal you guys, and elevate voices replaces empower, which used to be uplifting but is now condescending. The poor is classist; battle and minefield disrespect veterans; depressing appropriates a disability; migrant—no explanation, it just has to go.

Equity-language guides are proliferating among some of the country’s leading institutions, particularly nonprofits. The American Cancer Society has one. So do the American Heart Association, the American Psychological Association, the American Medical Association, the National Recreation and Park Association, the Columbia University School of Professional Studies, and the University of Washington. The words these guides recommend or reject are sometimes exactly the same, justified in nearly identical language. This is because most of the guides draw on the same sources from activist organizations: A Progressive’s Style Guide, the Racial Equity Tools glossary, and a couple of others. The guides also cite one another. The total number of people behind this project of linguistic purification is relatively small, but their power is potentially immense. The new language might not stick in broad swaths of American society, but it already influences highly educated precincts, spreading from the authorities that establish it and the organizations that adopt it to mainstream publications, such as this one.

Although the guides refer to language “evolving,” these changes are a revolution from above. They haven’t emerged organically from the shifting linguistic habits of large numbers of people. They are handed down in communiqués written by obscure “experts” who purport to speak for vaguely defined “communities,” remaining unanswerable to a public that’s being morally coerced. A new term wins an argument without having to debate. When the San Francisco Board of Supervisors replaces felon with justice-involved person, it is making an ideological claim—that there is something illegitimate about laws, courts, and prisons. If you accept the change—as, in certain contexts, you’ll surely feel you must—then you also acquiesce in the argument.

In a few cases, the gap between equity language and ordinary speech has produced a populist backlash. When Latinx began to be used in advanced milieus, a poll found that a large majority of Latinos and Hispanics continued to go by the familiar terms and hadn’t heard of the newly coined, nearly unpronounceable one. Latinx wobbled and took a step back. The American Cancer Society advises that Latinx, along with the equally gender-neutral Latine, Latin@, and Latinu, “may or may not be fully embraced by older generations and may need additional explanation.” Public criticism led Stanford to abolish outright its Elimination of Harmful Language Initiative—not for being ridiculous, but, the university announced, for being “broadly viewed as counter to inclusivity.”

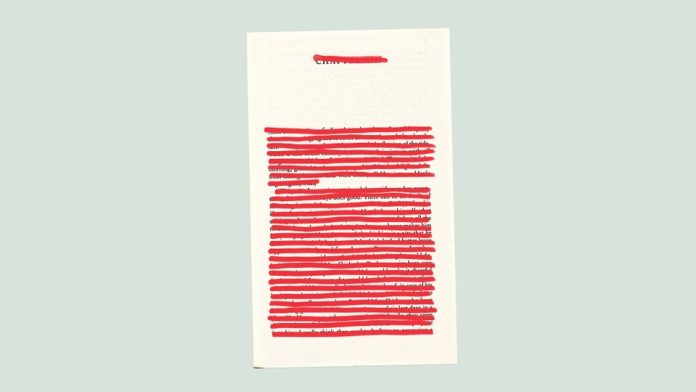

In general, though, equity language invites no response, and condemned words are almost never redeemed. Once a new rule takes hold—once a day in history can no longer be dark, or a waitress has to be a server, or underserved and vulnerable suddenly acquire red warning labels—there’s no going back. Continuing to use a word that’s been declared harmful is evidence of ignorance at best or, at worst, a determination to offend.

[Conor Friedersdorf: The AMA embraces leftist language—and leaves patients behind]

Like any prescribed usage, equity language has a willed, unnatural quality. The guides use scientific-sounding concepts to lend an impression of objectivity to subjective judgments: structural racialization, diversity value proposition, arbitrary status hierarchies. The concepts themselves create status hierarchies—they assert intellectual and moral authority by piling abstract nouns into unfamiliar shapes that immediately let you know you have work to do. Though the guides recommend the use of words that are available to everyone (one suggests a sixth-to-eighth-grade reading level), their glossaries read like technical manuals, put together by highly specialized teams of insiders, whose purpose is to warn off the uninitiated. This language confers the power to establish orthodoxy.

Mastering equity language is a discipline that requires effort and reflection, like learning a sacred foreign tongue—ancient Hebrew or Sanskrit. The Sierra Club urges its staff “to take the space and time you need to implement these recommendations in your own work thoughtfully.” “Sometimes, you will get it wrong or forget and that’s OK,” the National Recreation and Park Association guide tells readers. “Take a moment, acknowledge it, and commit to doing better next time.”

The liturgy changes without public discussion, and with a suddenness and frequency that keep the novitiate off-balance, forever trying to catch up, and feeling vaguely impious. A ban that seemed ludicrous yesterday will be unquestionable by tomorrow. The guides themselves can’t always stay current. People of color becomes standard usage until the day it is demoted, by the American Heart Association and others, for being too general. The American Cancer Society prefers marginalized to the more “victimizing” underresourced or underserved—but in the National Recreation and Park Association’s guide, marginalized now acquires “negative connotations when used in a broad way. However, it may be necessary and appropriate in context. If you do use it, avoid ‘the marginalized,’ and don’t use marginalized as an adjective.” Historically marginalized is sometimes okay; marginalized people is not. The most devoted student of the National Recreation and Park Association guide can’t possibly know when and when not to say marginalized; the instructions seem designed to make users so anxious that they can barely speak. But this confused guidance is inevitable, because with repeated use, the taint of negative meaning rubs off on even the most anodyne language, until it has to be scrubbed clean. The erasures will continue indefinitely, because the thing itself—injustice—will always exist.

[Helen Lewis: In defense of saying ‘pregnant women’]

In the spirit of Strunk and White, the guides call for using specific rather than general terms, plain speech instead of euphemisms, active not passive voice. Yet they continually violate their own guidance, and the crusade to eliminate harmful language could hardly do otherwise. A division of the University of Southern California’s School of Social Work has abandoned field, as in fieldwork (which could be associated with slavery or immigrant labor) in favor of the obscure Latinism practicum. The Sierra Club offers refuse to take action instead of paralyzed by fear, replacing a concrete image with a phrase that evokes no mental picture. It suggests the mushy protect our rights over the more active stand up for our rights. Which is more euphemistic, mentally ill or person living with a mental-health condition? Which is more vague, ballsy or risk-taker? What are diversity, equity, and inclusion but abstractions with uncertain meanings whose repetition creates an artificial consensus and muddies clear thought? When a university administrator refers to an individual student as “diverse,” the word has lost contact with anything tangible—which is the point.

The whole tendency of equity language is to blur the contours of hard, often unpleasant facts. This aversion to reality is its main appeal. Once you acquire the vocabulary, it’s actually easier to say people with limited financial resources than the poor. The first rolls off your tongue without interruption, leaves no aftertaste, arouses no emotion. The second is rudely blunt and bitter, and it might make someone angry or sad. Imprecise language is less likely to offend. Good writing—vivid imagery, strong statements—will hurt, because it’s bound to convey painful truths.

Katherine Boo’s Behind the Beautiful Forevers is a nonfiction masterpiece that tells the story of Mumbai slum dwellers with the intimacy of a novel. The book was published in 2012, before the new language emerged:

The One Leg’s given name was Sita. She had fair skin, usually an asset, but the runt leg had smacked down her bride price. Her Hindu parents had taken the single offer they got: poor, unattractive, hard-working, Muslim, old—“half-dead, but who else wanted her,” as her mother had once said with a frown.

Translated into equity language, this passage might read:

Sita was a person living with a disability. Because she lived in a system that centered whiteness while producing inequities among racial and ethnic groups, her physical appearance conferred an unearned set of privileges and benefits, but her disability lowered her status to potential partners. Her parents, who were Hindu persons, accepted a marriage proposal from a member of a community with limited financial resources, a person whose physical appearance was defined as being different from the traits of the dominant group and resulted in his being set apart for unequal treatment, a person who was considered in the dominant discourse to be “hardworking,” a Muslim person, an older person. In referring to him, Sita’s mother used language that is considered harmful by representatives of historically marginalized communities.

Equity language fails at what it claims to do. This translation doesn’t create more empathy for Sita and her struggles. Just the opposite—it alienates Sita from the reader, placing her at a great distance. A heavy fog of jargon rolls in and hides all that Boo’s short burst of prose makes clear with true understanding, true empathy.

The battle against euphemism and cliché is long-standing and, mostly, a losing one. What’s new and perhaps more threatening about equity language is the special kind of pressure it brings to bear. The conformity it demands isn’t just bureaucratic; it’s moral. But assembling preapproved phrases from a handbook into sentences that sound like an algorithmic catechism has no moral value. Moral language comes from the struggle of an individual mind to absorb and convey the truth as faithfully as possible. Because the effort is hard and the result unsparing, it isn’t obvious that writing like Boo’s has a future. Her book is too real for us. The very project of a white American journalist spending three years in an Indian slum to tell the story of families who live there could be considered a gross act of cultural exploitation. By the new rules, shelf upon shelf of great writing might go the way of blind and urban. Open Light in August or Invisible Man to any page and see how little would survive.

The rationale for equity-language guides is hard to fault. They seek a world without oppression and injustice. Because achieving this goal is beyond anyone’s power, they turn to what can be controlled and try to purge language until it leaves no one out and can’t harm those who already suffer. Avoiding slurs, calling attention to inadvertent insults, and speaking to people with dignity are essential things in any decent society. It’s polite to address people as they request, and context always matters: A therapist is unlikely to use terms with a patient that she would with a colleague. But it isn’t the job of writers to present people as they want to be presented; writers owe allegiance to their readers, and the truth.

The universal mission of equity language is a quest for salvation, not political reform or personal courtesy—a Protestant quest and, despite the guides’ aversion to any reference to U.S. citizenship, an American one, for we do nothing by half measures. The guides follow the grammar of Puritan preaching to the last clause. Once you have embarked on this expedition, you can’t stop at Oriental or thug, because that would leave far too much evil at large. So you take off in hot pursuit of gentrification and legal resident, food stamps and gun control, until the last sin is hunted down and made right—which can never happen in a fallen world.

This huge expense of energy to purify language reveals a weakened belief in more material forms of progress. If we don’t know how to end racism, we can at least call it structural. The guides want to make the ugliness of our society disappear by linguistic fiat. Even by their own lights, they do more ill than good—not because of their absurd bans on ordinary words like congresswoman and expat, or the self-torture they require of conscientious users, but because they make it impossible to face squarely the wrongs they want to right, which is the starting point for any change. Prison does not become a less brutal place by calling someone locked up in one a person experiencing the criminal-justice system. Obesity isn’t any healthier for people with high weight. It’s hard to know who is likely to be harmed by a phrase like native New Yorker or under fire; I doubt that even the writers of the guides are truly offended. But the people in Behind the Beautiful Forevers know they’re poor; they can’t afford to wrap themselves in soft sheets of euphemism. Equity language doesn’t fool anyone who lives with real afflictions. It’s meant to spare only the feelings of those who use it.

The project of the guides is utopian, but they’re a symptom of deep pessimism. They belong to a fractured culture in which symbolic gestures are preferable to concrete actions, argument is no longer desirable, each viewpoint has its own impenetrable dialect, and only the most fluent insiders possess the power to say what is real. What I’ve described is not just a problem of the progressive left. The far right has a different vocabulary, but it, too, relies on authoritarian shibboleths to enforce orthodoxy. It will be a sign of political renewal if Americans can say maddening things to one another in a common language that doesn’t require any guide.

This article appears in the April 2023 print edition with the headline “The Moral Case Against Euphemism.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.